Portraits of a Marriage

John Haberin New York City

Paul Cézanne: Portraits of His Wife

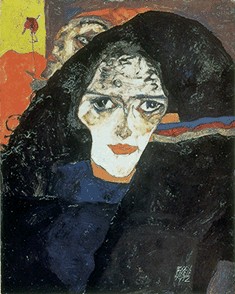

Egon Schiele Portraits

Paul Cézanne treated a mountain like a loved one and his wife like the face of a rock. That mountain was Mont Sainte-Victoire, overlooking Aix-en-Provence, and he returned to it again and again in his art. It taught him to seek mass and depth in an ecstasy of competing brushstrokes, with painting alone as a point of repose.

His wife was the former Hortense Fiquet, whom he met at art school. Could she have taught him even more? The Met thinks so, and it has assembled up to twenty-four of twenty-nine known portraits in oil, along with drawings, watercolors, and sketchbooks. It also sets aside a room for its own holdings on other subjects, including a version of that distant mountain.

The landscape appeared after Cézanne's death in the fabled 1913 Armory Show, helping to find an audience for modern art. So comprehensive an exhibition is an achievement, but "Madame Cézanne" claims still more. It sees the portraits as an intellectual collaboration, but their relationship as distant and fleeting. It sounds, in fact, like a summary of his art.

Portraits mattered to Egon Schiele, too. They were essential to his success—and to the shocks that he can still bring today. They also brought him a kind of peace with the demons who never left. Unlike Cézanne, Schiele was at his most obviously respectful in portraits of women. Yet they are unnervingly hard on himself. They help show as well the transition from Post-Impressionism to Modernism.

The woman and the mountain

Nothing came easily to Paul Cézanne, least of all representation. With the portraits, exact numbers are hard to come by for an artist who approached everything as a struggle, leaving some canvases incomplete and illegible—no small part of Cézanne's influence on Pablo Picasso and Cubism. When he had trouble, he might set a painting aside and start over, and yet finished paintings, too, turn on passages of bare canvas—what a philosopher has dubbed Cézanne's doubts. Did he have particular difficulty approaching his wife? One can find plenty of evidence either way. Her image can seem as distant as the mountain, but she sat for him for at least twenty years.

Paul and Hortense met in 1869, when she was nineteen and working for a bookbinder, and he was turning thirty. Her first portrait (not in the show) came three years later. He must have respected her independence and intellect, but he also found her sexy. An oil sketch from 1873 shows her with long hair, like a force of nature for Paul Gauguin, nude but for a pendant touching her chest. He was not satisfied, though, with that conception. From then on, she has her hair up in a bun and her hands like the blunt end of a club.

Had she grown closer to his ideal or further apart? Critics have seen her as sour and impenetrable, in the words of the curators, Dita Amory of the Robert Lehman collection with Kathryn Kremnitzer. If she seems remote, her image could reflect her personality. It also looks much like her in a surviving photograph. Not that the artist was exactly a treat either. He sought "to deal with nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone," but that may not have felt like a compliment.

They maintained separate residences, in Paris and Nice, and hid their relationship from Cézanne's family, which was unlikely to approve of her more humble background. She was at home in the city as he was not, which may account for the cramped feel of her Paris portraits. They did not marry until 1886—and then mostly to legitimize their son. By that time Cézanne made no secret of his lack of desire for her, and he left her out of his will. He also stopped painting her well before his death in 1906, even as his affection for the mountain deepened. She squandered whatever settlement she received from her son before her own death in 1922.

Yet she did sit for him for at least twenty years, and they traveled often to see one another. In a Paris portrait one can see the bolt on the door, as if to shut them more firmly together inside. Pencil sketches show her nursing and sleeping, the latter as early as 1880 and again approaching the end of the century. Cézanne was not observing her like that out of sheer duty. He also included a portrait in his first exhibition with Ambroise Vollard, in 1895, and her image is on the title page of a book-length catalog. Maybe the reduction of humanity to geometry really was a compliment.

Meyer Schapiro, the great art historian and critic, described her as the "tender image of esthetic feeling," with her unrevealing hands as the "eggshell delicacy of flesh." Her portraits culminate at Cézanne family estate in Aix in 1891, in their conservatory garden, with hints of domestic harmony. Her head flows together with a tree behind the wall, her bosom with flowers on the ledge beside her. In between she sat four times in the same red dress—because "only I," he insisted, "understand how to paint a red." Could only he have understood how to look at her? "Everything we look at," he lamented, "disperses and vanishes," much like their love, but art could still hope for eternity.

Neither surfaces nor distance

The portraits show Cézanne's growth up to the greater release of his last decade. They offer particular insight into the 1880s, when his paint thinned before returning with a renewed density. Paintings from around 1877 capture Hortense as a commanding presence in a blue dress and red armchair. Her hands come together as an obstacle to approach, but also as testimony to an active, independent woman. In one painting she sews, and in another she ties the bow of her dress, but mostly she just sits, her head bent forward. It speaks to humility, but also to an inner life—just as in a darker portrait of Vollard.

Already her firm colors are shot through with white from the layer beneath, where older artists would have marked the surface with shadow. The background, too, plays a role, with a corner of the room creating a division of color to either side of her head. Soon, though, underpainting takes on a more active role. Around 1885 her dress reduces to swirls of black against brown and white. Cézanne is looking for patterns and connections, here as in the wallpaper. He is also looking for their absence.

The four portraits in a red dress have the most intense color—and the greatest insight into an artist at work. They divide into pairs, the sitter in the precise same pose within each pair. Her isolation in one painting barely hints at her precarious angle. And then Cézanne adds a background, for a space true to sensation that single-point perspective could never have allowed. Her hands, her armchair, and even the blue smear of shadow against the blue wall in the other pair are constant, but not her lips and eyes. If her face is a mask, it is also a heartfelt tribute to uncertainty.

The four portraits in a red dress have the most intense color—and the greatest insight into an artist at work. They divide into pairs, the sitter in the precise same pose within each pair. Her isolation in one painting barely hints at her precarious angle. And then Cézanne adds a background, for a space true to sensation that single-point perspective could never have allowed. Her hands, her armchair, and even the blue smear of shadow against the blue wall in the other pair are constant, but not her lips and eyes. If her face is a mask, it is also a heartfelt tribute to uncertainty.

What, then, lies beyond surfaces? Is it an inner life or a truer perception, as implied in "Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible" at the Met Breuer? Is it an abstract conception of the human—or, in Schapiro's words, a tender, idealized, and graceful humanity? It helps to recognize what these portraits are not, including everything about the female in tradition. Hortense is neither saint nor sinner, the woman of high society nor café society. She is not the goddess, the innocent, or the whore—all under the fixity of the male gaze (or, for William Copley, its fluidity). A century later, a feminist could look at painting or film to see little else, but Cézanne was capable of more.

He cultivates ambiguity, but also something truer to his wife and to a marriage. On the one hand, the portraits are all about him and his art. Blankness equates to light, as well as to space for hand and eye together to fill. They run at once to the idealized and the unfinished, the opposition between the two very much at stake. They also, as Schapiro pointed out, "transfer his own repression and shyness" into the blankness of another person's gesture and face. They carry painting well past Impressionism's surfaces and into Modernism's perceptual and psychological complexity.

Still, they represent her, strong feelings intact. If a marriage was becoming unbearable, art would just have to bear that, without demeaning either party. It would also have to remember the feelings that they were leaving behind. It could not be only about distance. Think again of the mountain. For Cézanne, something need not be up close to be as tactile and precious as in one's hands.

Raw from the waist up

Portraits and self-portraits were essential to Egon Schiele and his success at the Academy in Vienna, which he entered in 1906 at age sixteen, after a precocious display of talent at the city's School of Arts and Crafts. They earned him a mentor in Gustav Klimt, who had followed much the same route. They found him allies in the New Arts Group of fellow students breaking away. They landed him in jail, accused of seduction and rape, after he and a seventeen-year-old lover slipped off to a small town in Bohemia and a police raid snagged over a hundred drawings. They also introduced him to his future wife and her sister, when he took residence across the street from them and hung out the window images of himself, naked and raw from the waist up. She became his most frequent model before his death from the flu epidemic in 1918.

They are the subject of "Egon Schiele: Portraits" at the Neue Galerie, which ought to know. No institution cares more for the journey from the Arts and Crafts movement to Austrian and German Expressionism. If there is one thing that unites the latter against Cubism, it is the human figure, in a treacherous place between narrative and introspection. It may be hard to apply the word modest to a display of Schiele, who anticipated quite well, thank you, what the Nazis called "degenerate art." Yet this really is a modest exhibition, with mostly works on paper from the collection, with some choice paintings and choice loans. It also gives those portraits a context one floor below, in Klimt and others.

They are the subject of "Egon Schiele: Portraits" at the Neue Galerie, which ought to know. No institution cares more for the journey from the Arts and Crafts movement to Austrian and German Expressionism. If there is one thing that unites the latter against Cubism, it is the human figure, in a treacherous place between narrative and introspection. It may be hard to apply the word modest to a display of Schiele, who anticipated quite well, thank you, what the Nazis called "degenerate art." Yet this really is a modest exhibition, with mostly works on paper from the collection, with some choice paintings and choice loans. It also gives those portraits a context one floor below, in Klimt and others.

There one meets the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 with Klimt as its president. That painter began with a delicate and detailed realism, before enfolding his subjects, especially women, in a lavish and decorative tapestry of gold and color. Oskar Kokoschka's jagged line further isolates figures from the background, in twisted poses that gain in psychological depth from their exaggerated hands. A more conservative artist, Richard Gerstl, sought similar ends through darker portraits with mirror-like highlights, while Max Oppenheimer stuck largely to faces. One can see something of them all in Schiele, as well as the cultural ferment of early Modernism. Where Gerstl pursued an affair with Arnold Schoenberg's wife, before suicide, Schiele's subjects included Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and more.

Schiele added the brooding, the flesh, and intimations of allegory. They start first and foremost with himself, with the colors of raw flesh against more neutral backgrounds. They include images of family and, again, himself. His gaunt limbs embrace a woman from behind, her full figure anchoring the painting's emotions and holding a little boy. The child looks up and to the side, whether desperate or hopeful. The artist must have felt the same.

He came by it fair and square, too, for all the encouragement that he received. He lost his father to syphilis, although an uncle readily adopted him and found a tutor for his art. He recorded his prison cell, although that means he was allowed to draw, and he got off with charges of immorality and time served. He served in World War I and saw its costs, but at a safe remove. He found clients, among which an industrialist gets Oppenheimer's sobriety and a gynecologist Kokoschka's stabbing fingers. And then he succumbed to the Spanish flu.

The show feels modest compared to a survey of his art thanks to the Leopold Collection at MoMA in 1997, even at well over a hundred works, but revealing all the same. It hangs works on paper, Salon style, in thematic groups, starting with the artist himself. Men run to wealthier clients, women to not quite professional models. It cuts corners here and there, in its gentle view of the artist. It does not include a portrait of his underage lover—or even deign to mention that he had a lover at the time of his arrest or marriage. Could even Schiele admit what the raw edges say about him?

Portraits of Madame Cézanne ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through March 15, 2015, Egon Schiele portraits at the Neue Galerie through April 10. A related review looks at Cézanne drawing.