Which Came First?

John Haberin New York City

Chinese and Japanese Painting and Calligraphy

The Three Perfections: The Cowles Collection

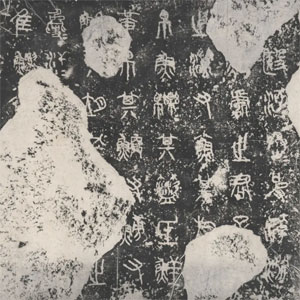

The oldest work in a show of "Chinese Painting and Calligraphy" is neither painting nor calligraphy. You might not know that, though, which only adds to its fascination at The Met.

It sure looks like calligraphy, but the characters have turned a ghostly white. Nor do they appear alongside a landscape as in so much Chinese art, although they seem to inhabit one—blending into a rocky, watery, or forested expanse. It takes on the texture of landscape as well, with eerie white slabs against a grainy black.  As long ago as the fifth century B.C.E., an unknown artisan carved the cryptic characters into stone before rubbing them with ink and transferring them onto paper. Long before photography, it is the ultimate paper negative. It should have you wondering at the relationship between painting and calligraphy in the centuries of art to come.

As long ago as the fifth century B.C.E., an unknown artisan carved the cryptic characters into stone before rubbing them with ink and transferring them onto paper. Long before photography, it is the ultimate paper negative. It should have you wondering at the relationship between painting and calligraphy in the centuries of art to come.

Chinese painting and calligraphy—it must sound like the entirety of Chinese art, right down to Tong Yang-Tze today. And the Met often rehangs its Asian wing to showcase its collection, most recently in its space for Korean art. Sometimes the rooms for China convey a theme, like "Companions in Solitude," whereas this time they approach a comprehensive history. Far be it from me to try for one myself. Consider then an amateur's chance impressions and a single question: what are painting and calligraphy doing together in the first place?

Oh, and does a dog have a Buddha nature? A Zen master's no was brief and clear, but then who knows what a dog might smell on a street near you? Then, too, nothing is unequivocal in a koan—or in a thousand years of Japanese art from the Mary and Cheney Cowles collection. Its real and promised gifts are substantial enough to fill ten rooms off the museum's Asian wing and its Chinese art, space enough to give a folding screen, a book, or a single scroll an alcove to itself. Sculpture alone could make you feel that you have entered a darkened temple or a tea house, with nowhere to stand apart from its guardians. An arrangement without regard for chronology may make you wonder if anything has changed or can ever change, until, that is, you stumble onto the present.

The show opened just days after the rehanging of the galleries for Chinese art right next door, to feature painting and calligraphy—often as not meaning poetry. And the show's title promises to separate the three, as "The Three Perfections." Yet nobody's perfect, and the Japanese insist on it. Think of Buddhism as the way to peace? Here the very first sculpture, a god, bears a sword to protect enlightenment from the likes of you. Another deity has a "wisdom fist." And yet wisdom itself cannot transcend human imperfections, for all its resounding no.

Seekers of enlightenment still debate Zhaozhou's no. For the Met, no means no, but could the Zen master have meant only the common image of a dog as a lowly creature? For a believer, everything in this world has a Buddha nature, and a dog has only to realize it. No wonder the sternest of guardians have a wider nature. In statues, the gods frown, but their robes flow freely, and gold enhances every fold. Nothing here is immune to delight, where even a stone for the artist's ink may bear gilding.

No old tree

You may take for granted that Chinese poetry and landscape were conceived together, in contemplating art and nature. That early work, though, has no true landscape at all, and each stage in its creation ruled out the fluency and precision of a fine brush in the artist's hand. Other works have at most a token inscription, in descending letters. The Met throws in other media as well, with enamelware, porcelain, and silver for what the painted images represent. The installation ends with three scrolls of portrait busts from the 1700s. The interplay between Asia and the West has begun in earnest, and the fluidity of ink has given way to hard outlines and firm color.

Those portraits may compile a family history or a procession of scholars, but then most Chinese art looks to its ancestors. Could a backward glance be the secret of pairing art and text as well? The show opens with exactly what you might expect—sheets of painting and calligraphy mounted together. They stake out a point of origin, a millennium ago or more, only they date from up to three hundred years apart, and dates for either one are hard to pin down. The Met calls its hanging "roughly" chronological, and you can see why. It can still display a coherent history.

Is it about shared visions or influences, and can one even tell the two apart? Often the text, clear and dark, vies with the subtlety and lightness of painting, but which came first? Calligraphy here may be a colophon (which, I fear, the Met does not trouble to translate)—not the date and place of publication as in printing practices today, but a kind of commentary, in poetry and prose. By the 1600s, though, poetry comes can take priority as well. Does that make the whole an illustrated book? If so, calligraphy is itself an art, both text and illustration.

Remember an old truth in Western literature—that the greatest of all must die, but trees live on as a glimpse of eternity? Shitao, a poet, knows that "no old tree can gain its youth again" either, and it makes him wonder why he writes. Poignant as it is, it returns to the theme of authority and ancestry. They are explicit when armies gather and palaces hold sway. They are clearer still in the 1300s, with drawings of women at court. They have hair like helmets, in parallel stokes that a greater freedom has yet to disturb.

Power may yet require accommodations (and the Met never once mentions religion). The women look after their children or stake a claim for themselves—at least one dressed as a man. Nestled trees with a crown in their branches may stand for Mongol rule or a peace surpassing it. In the fifteenth century, with Fang Congyi and others, authority must take a back seat to a softer handling, a mistier landscape, and a "beneficent rain." A scroll's long format from Zhang Yucai makes that rain all the more encompassing. Ancestry is everything, but there is no looking back.

Calligraphy, too, takes on a life of its own—bold to the point of ink blots, although never again the spatters of that ancient rubbing on stone drums. You can almost imagine a history akin to that of European art, from the certainties of the Middle Ages to the artistic personalities of the Renaissance. The Baroque, in this history, would take one last step, at risk of losing art's hand-won playfulness and atmosphere. Simplistic? Sure, and I cannot claim the expertise to say more. Still, it undermines the settled truths of a single, shared role and loving collaboration for calligraphy and painting.

A Buddha nature

Back in Japan, the Zen master says nothing in what I hesitate to call a portrait, nine hundred years after his death. In a screen to his left, a bird rests on a tree looking gloriously upward. To the right, more lowly birds seem almost comic figures—but then Zhaozhou himself looks eccentric, too, with his scraggly beard and a knife, perhaps a writer's tool, fallen to the ground. Here no means yes, and yes means yes to the world you know. Chinese art flaunts its connection to the past, with reverence. Here everything enters the present.

A black stone fountain, set on white pebbles, conveys a felt peace and physical motion that even the ancients rarely knew. It is not a recreation of a long-ago tea garden, but sculpture by Isamu Noguchi from the Met's modern wing. Calligraphy itself looks to the past for an artist's present impulse. Japan adopted Chinese writing for a phonetic alphabet of less detailed, freer marks, and an artist had to learn both. Wall text displays a poem as thirteen Chinese characters and again phonetically, from the Japanese, as two full lines. But then, as a translation has it, "our joy is limitless."

A black stone fountain, set on white pebbles, conveys a felt peace and physical motion that even the ancients rarely knew. It is not a recreation of a long-ago tea garden, but sculpture by Isamu Noguchi from the Met's modern wing. Calligraphy itself looks to the past for an artist's present impulse. Japan adopted Chinese writing for a phonetic alphabet of less detailed, freer marks, and an artist had to learn both. Wall text displays a poem as thirteen Chinese characters and again phonetically, from the Japanese, as two full lines. But then, as a translation has it, "our joy is limitless."

The Japanese writing system may appear separately, in graceful curves or as little as three letters and a spot of ink. Or the systems may blend into one another and into realism. Those curves adapt easily to stones, streams, and flowers. A single scroll may combine writing, patterning, and flowers. One god rests on a lotus, where attendants bring their presences and shadows as well. Who needs another wooden god with eleven heads?

When China enters the eighteenth century, its nods to the West speak of an empire's decline. Japanese art is just getting going. A scroll of "immortal poets" gives them individuality and a sense of humor that Chinese art never felt. A growing emphasis on color allows trapezoids that add perspective, although not Europe's linear perspective. It also allows a story, like the eleventh-century Tale of Genji, to unfold in an enormous folding screen. Like views of Edo from Hiroshige, at the Brooklyn Museum, it could take place in a far older landscape or in Tokyo today.

Noguchi himself invites contemplation of both past and present. Water Stone could be a found object or painstaking carving, with an eye at once to tradition, Modernism, and Minimalism. Water from this fountain does not spout up but rather ripples off the black tabletop onto white stone. A blond wood screen descends to maybe shoulder height. It sets the space of the ceremony apart from the viewer, who can nonetheless linger and belong. The work presents a complementary view from the other side, obliging a second encounter after a prolonged exposure to Japanese art.

I shall never get over my suspicion of a museum's catering to collectors in exchange for gifts. I cannot easily explain this show's arrangement—or a title that its wealth of materials hastens to ignore. It also includes a glass deer from Kohei Nawa in 2011, an oversized paperweight that I should just as soon had never appeared. Then, too, there is no challenging Chinese painting, calligraphy, and poetry. That is why Japan took it as a model. Still, neither is there challenging Japan's thoughts of transcendence and its all-too-human refusal.

The new installation of Chinese painting and calligraphy ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 5, 2025, the Cowles collection of Japanese art through August 3.