Who Needs Painting?

John Haberin New York City

Woven Histories and Jovencio de la Paz

Who needs painting anyway? Who, for that matter, needs paint? Maybe no one, but you can still be grateful for "Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction" at MoMA and Jovencio de la Paz.

Materializing abstraction

The question has come up again and again, from the moment Robert Rauschenberg found the materials of a "combine painting" in the debris of art and life. It came up when Tristan Tzara could endlessly repeat Dada and refuse to call it art. Denial could itself be art, by the very definition of conceptual art.  It could also be an imperative, as long "pure painting," some said, refused to ask who gets to exhibit painting in the first place, baring his (male) art school credentials and his soul. Wall paint still had its uses, for how else could a curator keep the wall clean enough for erudite text, damning or explaining it all. Postmodernism and diversity insisted on it.

It could also be an imperative, as long "pure painting," some said, refused to ask who gets to exhibit painting in the first place, baring his (male) art school credentials and his soul. Wall paint still had its uses, for how else could a curator keep the wall clean enough for erudite text, damning or explaining it all. Postmodernism and diversity insisted on it.

Painting's very life came for a while to reside in its material being. And its material being, it often seemed, came to reside in anything but paint. Still enough of a Luddite to resent weaving by anything but by hand? As recently as twenty years ago, I could not help noting just how often artists treated craft as testimony to traditions as diverse as a day in the galleries. The weave of fabric could play the role of drawing and colored threads the part of paint. Refuse to stretch a canvas and it becomes a hanging.

My own encounters with tapestries has all but lost its novelty, and allusions to East Asian, African, Islamic, Native American, and Latin American craft have lost much of their specificity as well. That is not to say that the art fails—or fails to address a real need. A snip here and a loop there and you have a curtain, a carpet, a tablecloth, or a home. MoMA, though, has in mind something else. It pushes weaving not to its origins, but back to the future. It sees a new beginning where people have long looked for one, back in early modern art.

It is not the first show to interweave history and contemporary art. Museums everywhere feel the pressure these days to include new voices, because museum-goers want what they know and what patrons can afford—not dead people, but the living. Just last year came "Weaving Abstraction" and "Crafting Modernity"—and I dare you to remember which is which. The first looked to the Incans for Minimalism's grid. If its handful of contemporaries included Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Lenore Tawney, and Olga de Amaral, well surprise, for here they are again at the Museum of Modern Art. Suffice it to say that none of them is Incan.

Puzzled by the promise of "Modern Abstraction"? Was there a premodern abstraction, and can MoMA quit before things get too postmodern? Try not to split hairs or unravel all the threads. The curators, Lynne Cooke and Esther Adler, proceed more or less by artist. If the working compromise between chronology and motif breaks down now and then, it has a point. It is asking what holds weaving and abstraction together.

So who needs painting—and, for that matter, who needs weaving? The show has no apology for reweaving history. It is finding a place for craft in the austerity and creativity of modern art. It can then discover a greater role for women. Curators have been out to recover the female half of couples that changed the face of art, including Anni Albers in Minimalism, Sonia Delaunay (apart from Robert Delaunay) in Orphism, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (apart from Jan Arp) all over the map. They get things off to an impressive start, but can the momentum last—and I answer with what the exhibition really shows next time.

Abstraction as experiment

That opening tells the story pretty well all by itself. Taeuber-Arp was a painter, puppeteer, and performance artist, while Delaunay was a dressmaker as well. Throw in "personal uniforms" for Andrea Zittel, and painting has become design for art and life. The exhibition will never be half as coherent again, and its unraveling could be the real narrative of modern art. What, though, holds its threads together? It depends on the weaver.

The show can hardly claim a history of weaving, through millennia of human experience. Neither does it ask why Modernism adopted weaving and what that changed. Nor does it tell of weaving's growing claim on art today. The few exceptions, like Zittel, seem like fortunate mistakes. Nor, too, does it present weaving as "women's work," given at last its due. Restricting things to women would be a shame, but that still leaves the question of who makes it through the door.

The Modern does not present weaving as a particular practice. A large last room leaps from fabric to basket weaving—and from delicate materials to sculptural mass. Martin Puryear cultivates smooth surfaces with a vengeance. Basketry also sacrifices abstraction to functionality and human form. The show does not so much as stick to weaving. Painters include Jack Whitten, the African American, his only weave the cuts of his razor through thick oil.

Perhaps the only weave that matters is the weave of history. Or could it be the rectilinear weave of geometric abstraction? One sees it in the visually charged surfaces of Agnes Martin or Jeffrey Gibson with their debts to Minimalism and to Native American rituals. Right at the start comes Fire in the Evening, oil on cardboard by Paul Klee. And the greatest unraveling comes from Ed Rossbach, whose lace and bleached cotton seem to come apart before one's eyes.

I thought back to Beatriz Milhazes, whose "pattern and decoration" I had seen only just before at the Guggenheim Museum. Surely if anyone has the weave of abstraction at its wildest, she does. Its patterned circles and the symbols they contain evoke the rhythms and colors that she knows so well from Brazil, where they enter the movements of bossa nova, the Carnival in Rio Tropicália, or just daily life. Her materials came to her from home as well, including shopping bags, chocolate, and candy wrappers. Woven textures enter her work quite naturally, as she layers acrylic on plastic as a medium for transfer to be peeled away. And yet it is only paint.

I thought back, too, to an artist whose weave I had seen just days before in Tribeca and now again amid the weavers at MoMA, Ellen Lesperance in Tribeca. Her fine grid takes on imagery from the changing density of fabric and paint alone. It may hint at faces, totems, or the artist's hand. It may never reach the edge of her paper, as if set against the sky. But then abstraction is still an experiment.

Intelligent weaving

For a time now, artists have been turning to weaving for the craft of the ancients and the latest thing in painting. An unknown quantity has become all but a formula, a cruel observer might complain, and a tribute to "women's work" and a diversity of cultures has become just one style among many. You might as well delegate it to AI, the voice of authority continues, along with everything else. Really? I am not convinced, but Jovencio de la Paz already has, and the results could have you rethinking old and new. It might also have you wondering who is delegating what to whom.

Computer models can now turn out a text or an image in the style of anyone you like. Indeed, it has no choice, since a program cannot act without instructions, and there is no telling a machine just to make something great. Who gets to define great? And if the instructions call for something original, can it still claim originality? I argued for a similar "postmodern paradox" in starting this Web site, and it helped me rediscover Modernism and art history. Now AI could be the ultimate postmodern.

Computer models can now turn out a text or an image in the style of anyone you like. Indeed, it has no choice, since a program cannot act without instructions, and there is no telling a machine just to make something great. Who gets to define great? And if the instructions call for something original, can it still claim originality? I argued for a similar "postmodern paradox" in starting this Web site, and it helped me rediscover Modernism and art history. Now AI could be the ultimate postmodern.

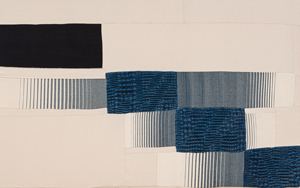

de la Paz makes a point of recovering the past, but as a collaboration with an uncertain future. This comes to Tribeca from not just any textile maker, but a Jacquard loom—or rather a digital Jacquard loom, if you can imagine that. But then a loom required instructions long ago, and automation had a cost in lives and livelihoods from the first. Yet it could adapt to shifting instructions, too, like those of an artist. It also produced practicality and beauty. It is, says the artist, "El Lugar de los Milagros" (or "The Place of Miracles").

The show's title is not just a lie. Up close, threads pop right out of the background. Step back, and the shimmer belongs to something like Op Art, as black verticals come closer to or farther from each other. The artist works in series, including grids and flattened circles, bringing the work that much closer to late Modernism. More often than not, the coarse weave leaves plenty of fabric unused. introduces the equivalent of unpainted canvas. It also breaks the symmetry.

Who, then, broke the symmetry? The artist has a shifting identity even apart from AI. Born in Singapore, de la Paz lives and works in Oregon. If the name sounds Mexican (and peaceable), the show's title quotes a site in Oaxaca. Oh, and he or she prefers they. I cannot swear that this is LGBT+ art, but it has many loves and many collaborators.

The show overlaps Marina Rheingantz in Tribeca, a Brazilian who produces art of the Americas and a shifting, shimmering weave of paint alone. She works large, laying a fluid background of soft colors before overlays of scattered paint. Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, and color-field painting loom over everything. Once again, what was past is new. AI and a loom can compete with this, but who gets to say so? AI may yet take a miracle.

"Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 13, 2025, Beatriz Milhazes at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 7, Ellen Lesperance at Derek Eller through May 24, Jovencio de la Paz at P.P.O.W. through June 21, and Marina Rheingantz at Bortolami through May 31.