In an Empty Room

John Haberin New York City

Trisha Donnelly, Oscar Murillo, and Tony Cokes

Fiona Connor and Jean-Luc Moulène

If a tree falls in a forest and there is no one to hear it, does it make a sound? At the very least, it makes art.

Trisha Donnelly is showing off The Shed, the new cultural center of Manhattan's Hudson Yards, by leaving it mostly dark and bare. It challenges you to locate the art—and the costs of climate change. Like Oscar Murillo and Tony Cokes after her, it also challenges you to confront the brute face of gentrification, in a decidedly top-down real-estate development. It makes, too, as Shakespeare wrote about another death, "a great reckoning in an empty room."  Long Island City, in contrast, is gentrifying from the bottom up, and Fiona Connor shows off an arts space that preserves its past. She makes a show so bare-bones that she can call it Closed for Installation, while Jean-Luc Moulène considers his bones mathematically minimal.

Long Island City, in contrast, is gentrifying from the bottom up, and Fiona Connor shows off an arts space that preserves its past. She makes a show so bare-bones that she can call it Closed for Installation, while Jean-Luc Moulène considers his bones mathematically minimal.

Making a sound

For Trisha Donnelly, a fallen tree must make a sound, for art is always listening, even as so many refuse to hear. Much of the planet may be dying, like her two trees, but art can speak to that as well. She has the very first show in The Shed, even before its first "Open Call," with its architecture by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (designers of MoMA's expansion coming up), and it makes quite an impact. It puts to the test a gallery with, as yet, too few visitors, next to a shopping mall serving too little of New York. Like Ann Veronica Janssens and Michel François, it looks beyond that very concentration of wealth to a fragile state of nature. It also risks drowning global warming and goodness knows what else in sounds of its own.

One enters not through the plaza of the Yards, past a towering sculpture by Thomas Heatherwick, but through a side entrance, past a black curtain, and into a vast room empty but for a traffic cone at the end. Early visitors must have wondered if the galleries were open yet. The black curtain divides the room, in preparation for whatever is to come. Nothing beyond dates appears on the gallery's Web site, not even a title, and no wall text offers so much as hints. Soon enough, though, Donnelly relented at least a little. Off the escalators on top floor, a guard in casual dress points the way.

The guard also offers some much-needed advice: follow the opera. One can already hear it, the "Habanera" from Georges Bizet's Carmen, in a fabled performance by Leontyne Price—and it grows in intensity as one crosses the near empty space. An amp and two speakers share a second room along with two impressive tree trunks lying helpless on the floor. Donnelly has bound one trunk loosely with a pink ribbon and wrapped the broken limps of the other with plastic gauze. They could be bandages for a wounded planet.

The artist might be trying to save the earth with her bare hands. Then again, the ribbon could come as a failed gesture or sheer mockery, and the plastic could stand for all the litter that refuses to biodegrade. More plastic covers the ends of the work's messier fourth component—dozens of branches heaped in a corner and reaching to almost human height. Even so, this room, too, stands all but empty, and pools of moisture from the fallen trees are drying out. One might be grateful to slip behind the north wall for a view of the Yards and into the light.

Donnelly has a history of operatic conceptual and performance art, riding into one installation on a horse, and this is no exception. When she curated MoMA's collection in 2012, as "Artist's Choice," she did not shy away from big postwar art at that. Just what, though, does Carmen have to do with the death of trees? Are they both beloved but tragic heroes, like a model ecosystem in art by Anicka Yi or Maya Lin, and are she and nature alike the free spirits in a song titled "L'amour est un oiseau rebelle" (or "love is a rebellious bird")? Is Carmen speaking instead for climate change deniers and an unfeeling humanity when she asks, "When will I love you?" Alas, she answers, "Maybe never, maybe tomorrow . . . / But not today, that's for sure!"

Of course, ignorance for a critic like me is no excuse, even if I could not know that one trunk belongs to a redwood and the other to a pine. Still, Donnelly is willing to sacrifice a degree of coherence in the interest of darkness and impact. The Hudson Yards itself plopped down to the north of the Chelsea galleries and the west of Penn Station like a very rude and very expensive intruder. She does, though, suggest that the galleries hold real promise, along with the challenge to fill them more than halfway. For now, but only for now, they are even free. Whether one can still love them after she is gone remains, like Carmen's song, an open question.

Invitation or confrontation?

Oscar Murillo and Tony Cokes pick up where Donnelly left off. Like her, they leave The Shed all but dark and seemingly underused. Like her, too, they work large and are putting on a show. If they leave you on treacherous footing, they are also demanding political change—and demanding that you deliver it. Are they issuing an invitation or assigning blame? The show's title, "Collision/Coalition," leaves both options open, but equally in your face.

Murillo uses the half floor that Donnelly obliged one to cross on the way to art. Where she cordoned much of it off, he has shredded her black curtain as a medium and a maze. The pieces separate this half from that for Cokes, while allowing one to penetrate. They also divide the space into smaller ones for works on paper and big abstract paintings. The fabric lends its blackness to Murillo's slashing gestures and otherwise intense palette, after Willem de Kooning, with plenty of red, orange, and blue. Sometimes, too, it serves as the very surface for oil.

Where Murillo let loose canvas fall to the floor at MoMA in 2015, here it rises again as a stage curtain. As in the past, too, he is out to combine spectacle and political critique, but critique of what? The Colombian artist, based in London, has turned the wealthiest of Chelsea galleries into a Third World candy factor and used a basketball as a wrecking ball. Here the payoff comes on video, where actors wheel life-size mannequins from The Shed to midtown. The "procession" pays tribute to a mural for Rockefeller Center by Diego Rivera, whose inclusion of Lenin and assault on capitalism got it destroyed. Murillo might be picking up the pieces.

Do they add up, though, and whatever do the paintings have to do with politics? Cokes, in contrast, leaves nothing to chance. Where Donnelly plopped down just three objects (counting a pile of earth and branches as a third tree), he has three screens of explanations and exhortations. Like Murillo's fabric, they divide the space while allowing one to cross it both physically and with the naked eye. And where she piped in duly inspiring music, Cokes gives each video its own soundtrack, including rap and reggae—which The Shed provides on headphones and iPhones. Again as with Murillo, the screens also serve as ground, for plain fonts on monochrome LEDs.

Does the resemblance to PowerPoint have you expecting a lecture? Cokes provides not just one, but three—and not just bullet points. He expects you to read every word, drawn from art criticism and his hectoring imagination. One screen connects the 1988 Tomkins Square riots to the homelessness, police action, and East Village art scene that preceded it—and to a black musician now tempted to cash in. The second speaks of an artist, identified solely by an initial, as he tries to maintain his integrity in the face of success. The last considers a studio as a locus of creativity place for an artist or musician, along with its role in changing the neighborhood and displacing others.

Everyone here is making choices, and Cokes, an African American, sees them as your choices, too. The colors, fonts, and music, all dizzyingly close to the room's seating, are confrontational as well, but just who is winning? You may blink first, or you may choose to turn away. Is gentrification really class warfare, with artists on the front lines, or is it driven by inequality and a shortage of affordable workspace and housing for all? Cokes, though, knows that the choices are also his—especially in the gilded shadow of a shopping mall. His work in a 2013 group show (just a mile from Tomkins Square) critiqued online paranoia, but also embodied it. He and Murillo have an agenda a little too overwhelming for the art, but they are out to overwhelm you, too.

Cleaning up in Queens

Newcomers to Queens are cleaning up. True, Amazon backed off from a move to Long Island City after New Yorkers objected to paying in tax breaks the salary of every single promised new worker and then some. Yet the glass towers continue to rise, fast and furious— from a new waterfront park to the very edge of MoMA PS1. And, as usual when it comes to gentrification, artists lead the way. Julie Becker made her own home, and Fiona Connor has agreed to sponsor an annual window cleaning for a third-floor apartment. It may sound like a modest gesture, like another show's "Microwave," but big things can start small, and so it is with her installation at SculptureCenter.

from a new waterfront park to the very edge of MoMA PS1. And, as usual when it comes to gentrification, artists lead the way. Julie Becker made her own home, and Fiona Connor has agreed to sponsor an annual window cleaning for a third-floor apartment. It may sound like a modest gesture, like another show's "Microwave," but big things can start small, and so it is with her installation at SculptureCenter.

It may in fact sound invisible, and I could find no sign of her after a healthy walk to the windows on Vernon Boulevard. What, one might ask, has Connor contributed in performance other than a little cash? Or it may sound obsessed with decorum and light, befitting an artist from New Zealand at home in LA, even as Andrew Ohanesian takes a gallery apart and puts it up for rent. It may even sound less about gentrification than preservation, given decidedly low-rise housing over a burger joint. All that applies to her basement sculpture as well. It may be an installation, but is also Closed for Installation—and it will be until the show comes down and she gets it right.

One might well wonder if it is there at all. Much of the pleasure of SculptureCenter comes with the Maya Lin architecture, leaving the basement tunnels of the former trolley repair shop crumbling but intact. It dares visitors to distinguish contemporary art from electric meters and other hardware, all the more so with Connor. She leaves exact copies here and there of a stool, a folding chair, a paint tray, a tape measure, a level, a push broom, and more. One may never locate them all or pin them all down, but that is part of the game, between the invisible and the real. The center provides no labels or even its customary map.

They are all common enough and industrial strength, because they could all participate in their own installation. They could, that is, were they not bronze, although that lets them belong to the installation after all, as works of art. Like the windows, no doubt, Connor has left the tunnels bright, clean, and lasting, with sculpture to match. Is this art or anti-art, intervention or preservation? Is it a swipe at changes to the neighborhood to every side or their embodiment? At the very least, it takes the wind out of all those gallery signs in a hot market, reading "closed for installation" and turning the disappointed away.

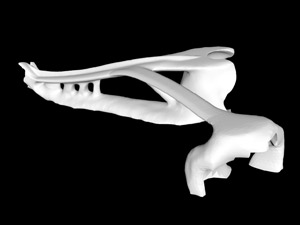

Back upstairs, Jean-Luc Moulène makes no bones about making sculpture. A single large work occupies the main gallery in pure white, as More or Less Bone. It comes with no end of contradictions, too, only this time not what the artist intends. It comes with no end of pretence as well. The sculpture arose from Moulène's residence in France's equivalent of Silicon Valley. It relies on software to transform simple shapes into an ungainly mass, but as the ideal of "the absolute minimum necessary."

Moulène began with a sphere, a spiral staircase, and a bone, but one can no longer discern them, not even in the hollows where the work breaks off. All art, he proclaims, works within constraints, but the shape looks arbitrary and unconstrained as it spreads across the floor in three directions. It has become "fleshless, scraped clean, hard, and without waste," but apart from the white it does not resemble human or animal anatomy. It has used "advanced engineering procedures" to achieve "formal optimization," but just what variables has it optimized? One can marvel at the scale of public sculpture and its roots in Modernism, like fossil forms for Gonzalo Fonseca and Isamu Noguchi. Or one can head off for a burger and optimally clean windows.

Trisha Donnelly ran at The Shed through May 19, 2019, Oscar Murillo and Tony Cokes through August 25. Fiona Connor and Jean-Luc Moulène ran at SculptureCenter through July 29. The review of Donnelly first appeared in a slightly different form in Riot Material magazine.