Beyond Pollock II

John Haberin New York City

Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock

Lee Krasner has nothing to apologize for, least of all not keeping up with Jackson Pollock. As described in part one of this review, a retrospective in Brooklyn traces her furious independence.Some years ago, New York University made the case for just how much Krasner and Pollock learned from one another. Take the rigor of Cubism, in the firm grid from her classes under Hans Hofmann, the painter of floating rectangles. Add in Pollock's Surrealist passion, and voilà—an American art at long last. Five years after her retrospective, her gallery places her career once again in context of her life with Pollock. Once again, she does not lose a thing from the association. A postscript takes a fresh look at Krasner in Chelsea, with an emphasis on collage.

Waste not, want not. Love a gesture? Repeat it, pushing its variations and its energy to the very edge of painted and raw canvas. If Abstract Expressionism was the ultimate in all-over painting, Krasner was the ultimate in all-over painters. Do not care for a first shot? Tear into it, at knife point, using its fragments as a starting point for something finer. Either way, the show insists, the key to her epic style was collage.

Try and try again

Lee Krasner described the wonder of first seeing Jackson Pollock in his studio. She arrived unannounced, after hearing about this guy in the same group show coming up, in 1941. For once, the moody westerner answered the knock. They had met before—danced together, in fact—but neither remembered. Now the stubborn New Yorker of immigrant parents took the initiative. She had shown the same determination in making it into that group show as a young woman.

Fifteen years later, she was just as determinedly nursing a dead alcoholic's reputation, even as Dorothy Dehner after her divorce from David Smith was turning away. At times she seemed all too dedicated to it, as if forever looking to him more than to her own work. Does her art, too, contribute to the case against her? She did change her format often, as if still unsure of herself. After eager-to-please Cubism in her school years, she covered easel-size canvas with tight rows of squiggles, like icons in a lost language. She had seen lettering in paintings by Bradley Walker Tomlin, not to mention Pollock, but she gives it a reserved, obsessive demeanor.

After Pollock's death, she moved to his larger scale, cycling for decades between a few bold forms and denser compositions. Twice for good measure, she shifted to collage of their past work, all torn into strips. She could have been staking her claim on her own self-destruction. She could have been riding on Pollock's greater heritage. Even her trademark—grand figures in earth tones, midway between a plant and a human—derive from his poignantly subdued final paintings. A friend of mine is convinced that she herself painted Pollock's Two and Easter and the Totem.

Still, there is far more to her majestic art and her persevering life. Back on the bottle, Pollock pretty much quit painting well before his death. When push came to shove, she did it for them both. Her collage and overlapping painted fields of color show her schooling in Cubism. Did it reflect a belief in European traditions that others around her had burst? Yet she used it to keep going when he could not.

She stuck up for her generation all the same, but with a detachment all her own. Asked about Pollock as "a life force," she called that

intellectual snobbery of the lowest sort. I go on the assumption that the serious artist is a highly sensitive, intellectual, and aware human being, and when he or she "pours it on" it isn't just a lot of gushy, dirty emotion. It is a total of their experiences which have to do with being a painter and an aware human being. . . . The painter is not involved in a battle with the intellect.

And then she would tell about her embarrassment when she first introduced Hans Hofmann to her future husband. Her old teacher started right in talking, of course, but he had to respect Pollock's answer. "Your theories don't interest me. Put up or shut up! Let's see your work."

Give and take

She was up to the challenge. After two great retrospectives, I can check the dates, and I keep finding that Pollock got there first, just as his peers from Willem de Kooning often agreed. And yet the last word counts, too, in art as in life. If "woman's work" means something intellectual and patient, demanding and giving, then so is art. It is not any one of its meanings—or even the sum of its meanings. It is a physical object to itself, and yet it ceases to exist if others stop responding and the painter stops giving.

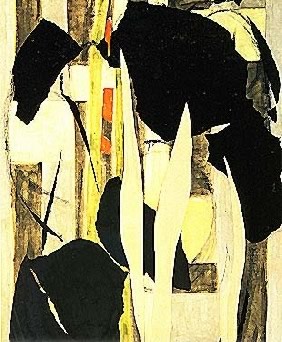

Dealing with her husband, surely something always had to give. Five years later, a Chelsea gallery describes its pairing of Krasner and Pollock as a "dialogue." One hears Krasner's voice everywhere, however, and it sounds wonderful. One hears it on entering, from a video of late interviews. One hears it resoundingly in the two largest rooms, with canvases from the 1950s and still larger and finer ones from the 1960s. They give up any lingering influence of WPA murals. They attain at last her near monochromes, of black, white, and earth tones—in the most striking of all, a blood red.

Over a scale of nearly fifteen feet, its leaf-like patches of warm color create an armature of interlocking X-shapes. They offer at once the structural integrity of steel beams and a Cubist exploration of a space no one eye could ever comprehend. The canvas appears from time to time as ground and as yet further patches of light brown. Over, under, and between them, Krasner adds more bursts of color and plain white, as if thickening the picture plane itself, again often in diagonals. On the very surface, the brushwork dissolves into not so much drips as a spray.

Pollock's drips weave where they will, with the end never clearly in sight. They strain toward an image, perhaps of nature or of a person, perhaps toward a signature or a mark in an unfamiliar language. They end up with a dialogue of surface and edge, of the viewer's eye and what it cannot fully penetrate. Krasner's great work after his death hardly defers to him for sheer force or for the trajectory of paint, but her confidence and her early modernist roots can make him seem to follow no rules at all. She pushes, and he responds by leaping off the edge. Perhaps the physicist who applied fractal geometry to Pollock could quantify the difference.

The show is covering familiar ground, especially after both their retrospectives. In that opening room, one can call it hauntingly familiar. Around the TV hang photographs and other recollections of their time together, mostly after they left the city for eastern Long Island. Arnold Newman famously poses them together, near an anchor that decorated their house, and it hangs high on the wall here, too, a reminder that nothing ever could quite anchor their lives. Then come sketches from similar years, including life studies, with Krasner the assured artist, Pollock the one who makes every nude, even with skin showing, into a flayed man. By the late 1940s, Pollock is diving into Surrealist signs, massive figures, and at last drips, while Krasner is chipping away at abstraction and the grid, square by square, until she gets it right.

Anyone has seen their histories before, in those separate retrospectives and the close look at their parallel development back at NYU. One knows by now how much they supported one another. One knows how Krasner looked after a damaged soul at the expense of her career. One knows how she modernized him and how, in return, he changed what Modernism meant to her and everyone else. One knows no longer to apologize for her or to expect the intimate, parallel development of equals. I do not hear a dialogue so much as her voice and his looming silence.

Cut-and-paste

One could compare them along with Barbara Rose, who writes the catalog, to Picasso and Braque. However, Krasner plays the role of both. She has Braque's equanimity, careful pace, and compositional grace, but also Picasso's ability to sop up everything. Pollock does not paint in tandem or rivalry with anyone, not even Rothko or Kooning. Maybe call them closer to Raphael and Michelangelo. The latter would have understand the rawness of Pollock's flayed man.

No one can match the density and influence of Pollock's drips or Willem de Kooning with his women and abstraction. Still, Pollock's very gesture, as he circled a canvas lying unstretched on the floor, most often leaves untouched the raw edges of canvas. And de Kooning's electrifying brushwork and imagery pull the eye to a work's very center. Nothing stops Krasner from making every inch count—even at the scale of her mosaics, covering the facade of an office building at the foot of Broadway in New York. What drove their leaf-like motif? And what about the warm reds and browns of so many similar works on canvas?

There, too, it may be time to think of painting as collage and radical fragmentation, and now a gallery helps. What I took to be the shapes and colors of raw earth could instead be those of canvas itself, after a knifing. The old formalist line about art as object takes on a new meaning. So does cut-and-paste, decades apart from Cubism before her and the digital yet to come. The knife edge also finds a parallel in Krasner's brush and charcoal, moving freely in her hand. While the show has its literal highlights in fields of yellow and blue, its most memorable works may have no color at all, apart from that of paper or canvas.

A gallery can add only so much to the Brooklyn retrospective—and I can add only so much to my review then. Her long-time dealer, Robert Miller, later paired her with Pollock, her husband, and the Jewish Museum set her beside African American abstraction by Norman Lewis. Still, it makes for a compact and revealing retrospective of its own. Most works date from the early 1950s, when Abstract Expressionism was reaching its peak, and from the early 1980s, when she fully emerged from Pollock's shadow. But is canvas pasted on canvas really collage, when it is not even mixed media? And did it really stand apart from the rest of her work or, alternatively, at its core?

It may not matter either way, given just how much is going on. A swatch of burlap functions as a vertical and as material, while deep blacks at their edges bring her brightest colors to the surface. I found myself remembering how much she brought to Pollock and he to her. She was the first abstract painter in their tormented family—and the closest to the roots of American Modernism. She was crucial to his entire generation's breaking free first of realism and then Surrealism. She led the way well before such celebrated women artists as Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell.

Then, too, the collaged canvas reminded me yet again of how Pollock laid canvas bare, and she had to take notice. His impulsive density surely pushed her hard as well. The show's one early work is hardly collage at all, with its thick white ground and biomorphic shapes similar to those of WPA muralists like Ilya Bolotowsky and Balcomb Greene. They called their collective American Abstract Artists for a reason. It makes clear just how advanced she was—and yet, too, how far she and American art had to go. In the end, she put Pollock's life and death behind her to get there.

Krasner's retrospective ran through January 21, 2001, at The Brooklyn Museum. The "Dialogue" between Krasner and Jackson Pollock at Robert Miller ran through January 28, 2006, and her collage at Paul Kasmin through April 24, 2021. Related reviews look more fully at Krasner in retrospective and Krasner and Normal Lewis.