African American Effigies

John Haberin New York City

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, Alexandria Smith, and John Wilson

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet set high standards—for herself, for art, and for America. Her show's very title sounds unrelenting, and her chosen medium looks unyielding as well.

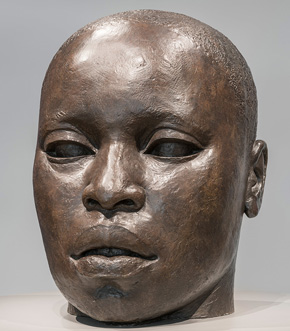

"I Will Not Bend an Inch," the Brooklyn Museum proclaims, and she offers nothing as malleable as clay. The museum sets out a shelf of her tools, and one can feel them cutting into hard and soft wood alike. Her subjects, like a Congolese and a Cossack, look unforgiving as well. Do not be surprised if they turn out to resemble the artist. If they are funeral effigies, they will find a decided refugee in Alexandria Smith in Queens and John Wilson at the Met as well. There is no getting around a memorial from them all to African American history.

Unforgiving

The very name Nancy Elizabeth Prophet puts those who encounter her on the spot. It is too late to change what an Old Testament prophet has seen. Her work looks like nothing so much as the chronicle in wood by Elizabeth Catlett (in the image here) at the Brooklyn Museum just months before. All it lacks is the knockout punch from Catlett's larger than life wood fist. While Catlett lived to see the civil rights movement and had relatives who knew slavery, Prophet's time on earth, from her birth in 1890, pretty much coincides with a history of modern art. Now if only it felt as free.

Her sculpture stands in one long line at the center of the room, and the museum gives her a time line as well, all but devoid of incident. Mostly she headed for the Rhode Island School of Design (or RISD) and made art. She is, though, is not so easy to pin down. Just by gathering her sculpture into a collective history, the display literally takes them off their pedestal. Watercolors render nature sparely, in casual loops, with soft colors for architecture—and one set of towers sways in the wind. Like it or not, it bends more than an inch.

If she ever drew a line in the sand, she stepped right over it. Her busts are not just women, not even close. Like the Cossack, they are also not just black. Their anonymous faces have a particular debt to classical art. In her hands, it becomes be hard to tell the cloaks of ancient Roman statuary from a woman's dress. Faces are themselves of uncertain ancestry and race, and titles speak of poverty and youth.

Are they gods, emperors, or African American labor? For Prophet, the categories run together, and African Americans have earned their place in history. Domestic labor and everyday human connections bring her closer to the gods. She was herself of mixed ancestry, with a black mother and Native American father, and the show identifies her as (ready?) Afro Indigenous. The closer her busts come to self-portraits, the lighter their hair. The more, too, they resemble masks.

She took an interest in diversity in her life as well. She taught at Spelman, the historically black college in Atlanta, and went to Paris to see art. Critics associate her with the "New Negro" movement, a coinage by Alain Locke, theorist of the Harlem Renaissance. That tight row of sculpture brings out the breadth an contradictions of race in America. All face out, in one direction or other, with much the curled lips and firm stares. They have the room outside Judy Chicago and her Dinner Party, an icon of feminism with its own love of goddesses.

Prophet changed the spelling of her name from Profitt to take responsibility for what she saw, with cause for outrage along with pride and hope. Has she entered history, or can she return to a sideline that Modernism had outgrown? For William Butler Yeats, art always takes the long view. "Though Hamlet rambles and Lear rages, / And all the drop scenes drop at once / Upon a hundred thousand stages, / It cannot grow by an inch or an ounce." It may yet, though, bend an inch.

Beyond the melting pot

When Alexandria Smith calls her work "Monuments to an Effigy," she speaks in the plural, even for a single moving installation. She also places art and memory at two removes from the African American experience, even for an African American artist today. Just that makes her history all the more urgent. She evokes a largely forgotten African American burial ground in what was then Olde Towne in Flushing, not far from the Queens Museum. (This is, after all, Flushing Meadow Park.) And she does so by inviting one to a ceremony on behalf of the living and the dead.

One enters past a first remove, a black wall broken by a slim window of stained glass, right next to "Mundos Alternos," a show of art and science fiction in the Americas. It suggests an opening, to the light or to the visitor, but also a fragment of something long since buried and lost. It is imitation glass at that—and mere color, like abstract painting, rather than an illustration from the Bible. Beyond that, everything is about blackness and, for the most part, literally black. Smith textures the wall with glitter, so that one feels one's presence all the more and so that the blackness shines. Objects within add local color all the same.

The Macedonia A.M.E. Church administered the burial ground until 1898 and served earlier as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Two pews hang side by side on a wall, as if swept up in the fervor of a ritual or risen from the dead. The facing wall has two legs that could belong to dancers or angels. Each curves around a shape like a burning bush or a flame. One last pairing could belong to an American church or a deeper history. African masks stand atop ionic columns.

Smith keeps doubling and redoubling, just as with her effigy and its monuments, even as a better-known African American burial ground in Lower Manhattan settles for the static and monumental. It allows objects to confront one another in the present, but also you. So does A Rooting Place, a black sculpture in the shape of pigtails, fingers, or roots. She speaks of them, too, as rising out of the ground, although they rest on a pedestal as a stand-in for an altar. So does a soundtrack as well, mixing quotes from Gwendolyn Brooks, the poet, with music by Smith and Liz Gré for cello and soprano. It has a touch of old-fashioned church music and a touch of gospel, as At Council; Found Peace.

Doubling, though, can be unnerving, as Doppelgängers or what Sigmund Freud called the uncanny. The objects here could represent ghostly counterparts or living memories. This is Civil War art updated for an ongoing civil war under Donald J. Trump. Its impressions recall absent bodies for David Hammons or the forced absence of African Americans in politics and textbook histories. Still, a doubling, like the plural "monuments," remains an openness to alternatives. Smith sees ionic columns as masculine and African masks as the property of women.

With Beyond the Melting Pot, by Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Nathan Glazer in 1963, one American ideal gave way to a picture of conflict but also diversity. A melting pot might still make sense, though, so long as one imagines its viscous contents poured out one pot at a time, leaving other layers below. Flushing is now home to the Mets and Chinese Americans, just past the Latino community in Corona, and the city paved over the burial ground decades ago for a playground. The Queens Museum arose on the site of another celebration of diversity, the 1964 World's Fair. Spooky, no, or maybe halfway uplifting? For an African American or a woman, it is not so easy to lay the past to rest.

One man's eternal

John Wilson lived his share of adulation as a black artist. He knew where he was going. The center of the action had already begun shifting to New York when World II crossed the oceans and he left to study with Fernand Léger in Paris. On his return home he guided more than a generation of Boston students with only a well-earned break, ending at his death in 2015. His head of Martin Luther King, Jr., rests in the U.S. Capitol and Eternal Presence in Boston's National Museum of African American artists. No black artist could claim more, forgotten or not.

Such sums up a not unspoiled achievement from a genuine achiever. Even now, you may wonder what to claim for his retrospective, in the section for works on paper at the Met in New York. It says something that his best-known works, those two sculptures, are literally larger than life. The first stands outside the exhibition as a fearsome greeting. Visitors are unlikely to have met him before. They were probably too consumed with fearsome times themselves.

Such sums up a not unspoiled achievement from a genuine achiever. Even now, you may wonder what to claim for his retrospective, in the section for works on paper at the Met in New York. It says something that his best-known works, those two sculptures, are literally larger than life. The first stands outside the exhibition as a fearsome greeting. Visitors are unlikely to have met him before. They were probably too consumed with fearsome times themselves.

Born in Roxbury, in Massachusetts, Wilson himself surely was. Not an overly packed exhibition, this one sticks to men and women doing their job. Malcolm X loses his life here as if it had to happen. Like the man elsewhere, in The Lynching, it is iconic. He is, as the show's title insists, "Witnessing Humanity," to capture the poetry with the politics. He is challenging anyone to look away.

This is not an easy exhibition space for sharing testimony, rarely given over to more than one artist. It all but begs you to put your personal admiration and concern aside. Even at part length, sculpture in small quantity takes over the show. Wilson lavishes care on bronze surface, for layers of studio and institutional light. Capturing the light would have been a helpful skill for his students. It becomes an essential one characterizing blackness.

That does not make him overbearing, just determined, like Prophet with her first raised to the sky. He included Nazi Germany among his subjects, but not to lecture. He spent five years in Mexico City, where he turned to the Mexican Revolutionary art of David Alfaros Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco. And he knew white men and women as students and teachers, too. Visitors to the Met meet quite a few on paper outside. They seem flattered to be there.

Then again, everyone seems flattered to sit for him, however punishing the black universe is in outcomes and however proud its people. He demands that people meet Eternal Presence as it looks forward and King as he looks inward. When he calls a presence eternal, he means it, too. A different artist might have demanded the elusive presence of art and spoke of two Americas. A different one would have found the conflict, too, in Trump's America. You will just have to see for yourself if you get it.

Nancy Elizabeth Prophet ran at the Brooklyn Museum through July 13, 2025, Alexandria Smith at the Queens Museum through August 18, 2019, and John Wilson at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through February 2026.