Sitting Still

John Haberin New York City

Objects of Desire: The Modern Still Life

Still life. In French, nature morte, dead nature. It sounds like a serious contradiction in terms.

If New York's Museum of Modern Art has its say, still life may find new life. "Objects of Desire" uses the genre to survey a century of art. From Cézanne till today, the twentieth century has toyed with simple objects, exposed in simple interiors. Along the way, this art definitely does not stand still. Wanted, dead or alive, it remakes the meaning of the visible world.

A still life is so easy to picture—the overturned glass of wine, the fruit never to be eaten, the almost flickering candle flame, a momentary stillness with an unsettling future. Is it unsettling enough for modern art? Or are Modernism and Postmodernism now a conservative tradition of their own? Maybe, but part of the show's fascination is the traditionalism of a great museum.

The still life of dreams

Word of mouth had me worried, starting with that mention of Paul Cézanne. It all looks suspiciously, The Times complained, like just another excuse to trot out the permanent collection. In person, I found plenty of signs of a conservative institution, but also much more. "Objects of Desire" is far more than a casual way to fill a lazy summer. It features many works from rarely seen collections alongside knock-outs from home. And for all of them, seeing them as still life means seeing new connections.

Carlo Carrà's Still Life with Triangle, for example, comes all the way from Milan. Carrà, painting in 1917, shows a bare perspective box. Its four austere objects rise right to the imagined ceiling. Two of them resemble a pitcher and a wine bottle, and yet one could represent a drafting tool. It is as if the room had contracted sharply, to the space of memory and the design of art.

Modeled harshly in grey and a single color, the objects approach abstraction. I now saw freshly the connection between an abstract painter in America, Patrick Henry Bruce, and his art's European origins. How deeply he altered American Modernism, with its ambivalent roots in realism. Also for the first time, I saw the overly refined compositions of Giorgio Morandi as mainstream Cubism without the Giorgio Morandi silence. All of this stood in one section of the Modern.

Further on, I faced Joan Miró, with his early magic realism. Now I could no longer dismiss it as a way station toward something truly "modern." It stood squarely in the unfolding of modern art, from Cubism to more dreamlike interiors. Luigi Ghirri does much the same with family albums as still life in photography.

Café nature

Margit Rowell, the curator, does something else unexpected. Thanks to her, the Modern makes contemporary art less of an afterthought for once. The show's theme, of painting as an evolving fiction, leads almost naturally to "postmodern simulacra"—art as willful fraud. I loved a stack of huge plates by Robert Thierren. They rise as formal as sculpture, but also as elegant tableware design. Fakery and reality, fine art and "low art" sat comfortably together.

In many other ways as well, Rowell acknowledges recent art criticism. Rebelling against formalism, many critics today have looked more carefully at what paintings are about. For them, realism never went out of style, it just got shaken up by the conventions behind reality.

From the Impressionists' first paintings of café society, they say, Modernism has pictured life. That means modern life, including the artist's own alienated days and nights. All these things had a story to be told, and an artist had the task of discovering what it really is to make meaning. They had to focus on the everyday.

Even a formalist might half agree. According to dignified defenders of abstraction such as Clement Greenberg, oil on canvas should be an object much like any other. Once again, painting is about ordinary things.

It is time then, the Modern believes, to recover the plain sense of things, especially when it can no longer be plain. It is time to turn to still life. Thankfully, after all that, Modernism stays as discomforting as ever. And why not? In French nature also means black, as in café nature. In this exhibition, I take my jolt of caffeine straight.

Getting up from the table

But is the museum right? Has art remained at all traditional? Start right with the phrase, still life. Surely art long ago stopped sitting still long enough to sit in for reality. In modern art at its best, images dance and weave in constant transformation. Besides, nothing these days is "natural." The exhibition itself shows why.

Art never escapes its history. Yet the artists here seem out to dismantle the whole idea of a genre. Got a painting that goes over here in the still-life room? Want to put another one over there—with abstraction, say, or maybe landscape, portraiture, and those self-portraits? Better think again.

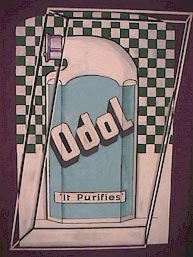

I have already mentioned the confusion of still life and abstraction, which made me wish the museum had included what Alberto Giacometti once called his Invisible Object. Carrà's refinement of the still life, say, makes it an extension of geometry. A Ginger Pot by Mondrian, too, announces its place in the development of abstract art. Stuart Davis even makes fun of his role in the game. His Odol, named after a brand of household cleaner, turns the labels on cans into squiggles, like an elegant abstraction by Cy Twombly in miniature. The only legible words are "It purifies."

The confusion gets worse for older genres, such as landscape. From Mikhail Larionov's foliage to René Magritte, his bedroom seemingly open to clouds, traces of the outdoors are never far away. Elsewhere, Magritte's Surrealism blithely labels a leaf with le table and a glass with l'orage, "the storm." Objects, genres, meaning, and fiction—all refuse to stay put. If Braque's and Picasso's guitars, also in the show, could have fallen out of a still life, they also look back to Manet's street musicians. They become street scenes, cityscapes.

Finally, people rarely sneak into these works, but portraits are everywhere to be seen. Still life had always hinted at a human presence behind the half-eaten meals, but Magritte again goes further. He calls one painting Portrait, and an eye (or perhaps an I) stares up from the place setting. With Second Choice, near the end of the show, Kiki Smith's mysterious objects of look to me like human organs. The modern still life, if such a thing exists, has turned portraiture literally inside out.

Painting at the K-Mart

Modern art could not possibly accept the old genres without transforming them, blending them, reaffirming them, and destroying them. Just a year ago, the Modern's own retrospective of de Kooning moved with dizzying speed between abstractions and paintings of women. Rowell wants art to explore "systems of meaning." To me, twentieth-century artists are much more like a pack of gamblers trying to bust the system.

They started by busting up genre painting, because it was just one more recent invention claiming authority. Rowell thinks of genres as age-old traditions. It would then make sense for Modernism to take up still life, the most humble genre of them all. That way, artists could reverse older values. In the process, the story goes, they could use reality to create a world of dreams.

This account has everything right except history. Genre painting of all kinds was still new at the end of the Renaissance, and their art-world triumph was later still. Genre categories finally came to the fore barely decades before modern art. Here is the story.

Renaissance painting began with the old task of experiencing the sacred. It evolved in no time into recording the sacredness of experience, and it did not stop there. The next four hundred years went about desacralizing things, including art.

In middle-class Holland of the sixteenth century, painting was there to be bought and sold. The genres, just starting to emerge from the backgrounds of religious painting a century ago, had to become clearly marked, like aisles in a K-mart. Only against that background could Rembrandt, Vermeer, or Saerendam make the story line—or a still-life prop in a girl's ear—feel ancillary to a subject's introspection.

Once the Dutch republic died, however, artists found new directions. Genres never did die off, as Chardin so gloriously attests, but they had to compete with grand commissions for palaces and estates. Beginning with Romanticism, they had to compete with the artist's vision as well.

Finally, especially in the nineteenth century, art's public broadened again, and this time for good. Museums formed, galleries and schools gained in power, and the signs went back up in my imaginary K-mart. The official genre definitions returned with a vengeance, as "traditional" ways of judging art—in the home and in the official French salon.

Of course, artists learned from and fought against the new institutions. At first, the avant-garde took up landscape and still life against history painting. Ultimately, however, artists had the sense to challenge art's very definitions.

Vanity and virtuosity

That includes the definition of still life, in competing traditions still visible in Susan Jane Walp or Rachael Catharine Anderson today. I can go right to the textbooks, a terrific account of Dutch Painting by R. H. Fuchs. He reproduces Harmen Steenwijck's Vanitas, painted more than three hundred years ago and now in Leiden. As director of the Stedlijk, Amsterdam's great museum of contemporary art, Fuchs can compare modern art and genre as few others. I use his definition of still life, but I shall compare it to the art now at the Modern.

The title vanitas, of course, points to a familiar message—reflect on death. Sometimes it needs a snuffed candle, and Vermeer offers up a whole allegory, but Steenwijck settles for a skull, by then the centuries' old prop for saints in meditation. Modernism, in contrast, has little use for tidy morals. When skulls comes back into art, Andy Warhol transfers them to canvas as blankly as Marilyn Monroe. In the world of John Cage, objects can drift in and out by mere chance.

The converse is a display of excess, the satiety and stability of possessing, the half-empty plates piled high, images of oysters and overripe fruit. Modernism, in contrast, is on the cheap. Morandi, Bruce, Carrà, or indeed Andy Warhol offer a few items near to abstraction, surrounded by startlingly barren spaces. Cindy Sherman submerges a dinner in vomit. John Chamberlain starts with the automobile scrap heap.

That excess includes the artist's virtuosity. The middle-class buyer was paying for a good show, including fine detail and realism. Moreover, virtuosity applied the mixed message of vanity and pleasure to the painting itself. In contrast, Modernism resisted realism, virtuosity, and use. I think especially of the ready-mades, such as Meret Oppenheim's fur-lined teacup or Man Ray with his Gift, a clothes' iron with tacks on its face. When photorealism returns with Postmodernism, Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work, Chuck Close, or Thomas Struth questions equally the reality of photographs and the personality of the artist.

In a traditional still life, all that virtuosity hinges on the art's special, fictitious lighting. As Fuchs explains, Steenwijck's even tonality derives from averaged sunlight and uniform, metallic colors. Modernism, in contrast, ranges from Max Beckman's harsh lights to installations, where the art gallery supplies the illumination.

Saluting Modernism

Still life, then, offered more than reminders of what wine glasses look like. It offered moralism, a display of excess, virtuosity, and dazzling lights. In short, a still life stood for quality.

The owner of a Steenwijck could look on it from afar, comfortably judging the vanity of the world—and his own. Modernism and Postmodernism have turned alike on art institutions and the viewer. Art takes a long time to judge, and it never lets one examine it from afar. Art and its audience are part of the same reality. The assumptions behind still life are gone forever.

Robert Rauschenberg is famous for saying he wants to act in the gap between art and life, and his combines succeed. A Jasper Johns Flag, also on display, represents a flag and is a flag. I could salute it. Approaching its luscious surface, I could describe it as carefully worked in encaustic. Alternatively, I could praise it as a slapdash, broadly painted collage of wax, oil, newsprint, and canvas.

What I cannot do is raise it on a flagpole. I cannot stand apart from a painting by Johns as I can from a fiction or a traditional symbol.

I feel my place even more in front of his target paintings, unfortunately not in this exhibition.  The owner of a still life need never feel out of place. With Johns, it is "as if his place before the painting were already occupied by virtue of the extreme measures that had been taken to stake it out."

The owner of a still life need never feel out of place. With Johns, it is "as if his place before the painting were already occupied by virtue of the extreme measures that had been taken to stake it out."

I have quoted Michael Fried, the art historian, writing about Manet's Modernism. Fried is describing paintings like A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. In it, a barmaid and a mirror seem to focus out front, confronting the painting's viewer. However, they also turn invitingly toward a boorish man in stylish clothing off to the right. As I critically examine the painting, I might as well be that pompous male cruising for action, but I am left with nowhere to stand.

Vanitas, or at least male vanity, has already lost its connection to fine-art genres. As Fried puts it, "the beholder sensed that he had been made supererogatory to a situation that ostensibly demanded his presence."

The fruit of Postmodernism

In Manet's Bar, a viewer enters the painting's carefully constructed reality. Since Manet, artists have reversed Fried's formula but kept its paradox. Art has entered the world, but at the price of leaving museum-goers too close for comfort. Take my favorite single discovery at the Modern's summer show. In the final section, from 1982, Mario Merz created a Spiral Table—well after his wife, Marisa Merz, came to a less recognized maturity. Iasmu Nogochi would have made a real lamp for the table—and sent it out for reproduction.

This literally is a spiral table, laid out with real fruit. Whereas the fruit in an old Vanitas is overripe, Merz's fruit has not a single blemish, fresh—but off-limits. It stands in a museum. Do not touch the work of art.

Steenwijck's classic still life included a shell, and Merz's beautiful spiral made me think of a cornucopia, a horn of plenty. I found myself coming closer and closer until I myself entered the spiral, following the table's edge. At the center, the ripeness dies. Merz has placed tree branches without leaves, in a stand that looks a little like an artist's easel. The art has cut off the viewer's own living reality, and there is nothing left but to turn back.

Ultimately, the Museum of Modern Art is still defending Modernism from the philistines. No wonder it stops well before contemporary still life, as if to defend art from any trace of academicism. It begs for the quality of fine art. It hopes to incorporate Postmodernism harmlessly, as a fitting climax to art's metamorphosis into fiction. It considers Modernism and Postmodernism alike as displays of the artist's subjectivity. That is why it confuses objects with still life. Not surprisingly, the exhibition excludes the rancid associations of Marcel Duchamp's urinal.

The Modern wants to insist on art as a supreme fiction, Marianne Moore's "imaginary garden with real toads in it." The powerful works on display suggest another future, beyond the Modern's reserve. As I left Merz's table, I had seen a real garden with imaginary toads.

"Objects of Desire" ran through August 26, 1997, at The Museum of Modern Art.