Photography's Magic

John Haberin New York City

Laura Larson, Scott Alario, and Christopher Williams

Remember spirit photography? Not that you were there in its heyday, in the nineteenth century, but then neither were the spirits. If you have any associations at all, you probably think of mistaken longings and a sham. Yet art, too, channels desires and artifice, almost by definition.

One can easily take for granted photography's claims to documentary truth and its theater, with hardly a thought to its contradictions. So does Laura Larson. Like Tim Wilson in painting, she evokes old photographs and modern interiors, in search of a woman's life. There she finds a dark magic, while Scott Alario finds a brighter one in image manipulation, but still for images of loved ones and what they treasure. Both photographers humanize its magic, while restoring the strangeness of a familiar medium. Strangeness need not mean distance.

Not everyone believes in magic. Christopher Williams describes his work since 2003 as a single ongoing project, "Eighteen Lessons on Industrial Society." He is selling himself short. For thirty-five years, his photographs have kept coming up with new lessons, none of them easy. His retrospective could serve as the final exam. If photography still has its strange magic, no one is more determined to cut through the mystery.

Are they friendly spirits?

For all their black magic, Laura Larson's photographs also capture everyday reality, one that threatens at any moment to disappear like a ghost. She attends to unmade beds, peeling walls, period rooms, and the confidence and baby fat of a twenty-first century adolescence. A balcony with a view of the Eiffel Tower recalls the Paris of Henri Cartier-Bresson and The Decisive Moment, while a woman swallowing or maybe disgorging lace could almost date to Surrealism. So could a woman's breast, a slim fragment of fabric hanging from its nipple like a chain. These scenes are as distinct as the transient spaces of Katherine Newbegin and the childhood indulgences of Rineke Dijkstra today, and one could well treat the show as three or four distinct bodies of work, including large color photographs and smaller ones in black and white. All, though, look back further, to photography in search of spirits.

The titles alone of past series suggest both her range and her obsession. "Domestic Interiors," "Well Appointed," "My Dark Places," "Apparition," "Asylum"—they all barely keep away the demons. The first obvious apparition, though, comes well into the current show, with work from 1996 to 2012. In Day Room from 2005, a pillar of light rises before tall bay windows. The puff of light might have shattered the floor below it or emerged from the rubble. Other ghosts inhabit empty interiors and forest clearings.

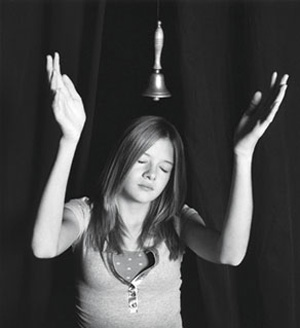

They are not the only signs of the departed. A sign for Internet service identifies an unmade room as a hotel, and one does, after all, speak of both guests and the dead as "checking out." Mail slipped under a door piles up as Estimated Time of Death. Larson's female nudes are creepy enough on their own, while a third arm encircles the adolescent girl. Not that her subjects are altogether helpless. That girl is also capable of suspending a table in midair and summoning a bell over her head.

It is a charmingly old-fashioned bell, the kind that might once have rung through a New England madhouse, and revisiting accounts of witches is still a feminist issue. For influences, Larson mentions Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann, Martha Rosler, and Yoko Ono. All four women made themselves vulnerable in performance while asserting control, and Larson speaks of recasting them in her art as "latter-day mediums." For her, empty rooms and narrow clearings take on feminist overtones. Mirrors and close-ups turn them into spaces of confinement, much as women were long confined to the home. "What," she asks in an interview, "does a feminist photographic practice look like if there are no bodies?"

For starters, it looks inhabited. A hotel room also has associations with trysts. Another unmade bed has a lump under the sheets, hastily or never abandoned. Larson, who has worked in film, still implies a narrative. And then, as with spirit photography, she leaves it up to the viewer's longings to fill out the story. This being art rather than a con game, the story might even be true.

Spirit photography arose when science flourished alongside Romanticism, as two ways of naturalizing the supernatural. It also came about when photography's ability to capture presences seemed like magic—or, as with Julia Margaret Cameron, like theater. Like Cameron's, Larson's photography is staged rather than manipulated. She arranges the rooms, and she uses cigarette smoke rather than double exposures or Photoshop for her spirits. Her magic act may call up both a woman's self-assertion and her demons. Still, she still keeps things real.

Do you believe in magic?

Scott Alario believes in magic, the kind in a little girl's bedroom or his own backyard. He always felt that his family belonged not so much to him as to the universe, ever since he became a father. One past series relied on a UV sensor meant to track game, lending eyes the beady shine of extraterrestrial beings. They have the optimism of much American Surrealism and Surrealism beyond Paris, but they belong to something wilder and the night. Another series stared directly at the sun, and a third sums up Alario's world in its title, Our Fable.

He is still after that shared fable. Visitors to "What We Conjure" in 2014 entered their private world just in stumbling on the gallery, up a back elevator on an active Lower East Side block, but with minimal street signage. The show held just ten large-format prints (although the full series runs longer), presumably because conjuring takes care and attention. The title could be a pun, leaving open who is playing tricks, the subject or the photographer. Yet the magic lies just as much in their intimacy and collaboration. Eight years later, on the Upper East Side, the magic deepens as Alario translates digital photos into analog negatives in black-and-white—again with the ghostly look of x-rays, but with added color and a greater profusion of flora and fauna in an older child's field of vision and in her hands.

They go about their daily routine, napping or hanging out by the clothesline, but her skin has grown sheerer and her gaze more persistent. In the earlier show, the father does the dishes, back to the camera, the child on his shoulders raising her arms to the window and loving every minute. Another past series dropped children into vintage prints of arctic and lake explorers.  Newer work requires less irony and less special pleading. The masks are all dime-store plastic. Their wearers keep all hours all the same.

Newer work requires less irony and less special pleading. The masks are all dime-store plastic. Their wearers keep all hours all the same.

Photography has always veered between powerful impulses, to special effects and the truth. Think of the gleam of a photogram and the testimony of street photography. Yet the two impulses have a way of spilling into one another. Which matters most when Robert Mapplethorpe and Mapplethorpe portraits confront death? Has Photoshop dispelled the magic once and for all, or is it just another tool in the service of the imagination? Alario's twist is to perform his magic on the cheap and to make it as familiar as home.

In an earlier series, the mother kneels, eye clothed, while holding a white disk to catch the moonlight, like a moon itself. The father stands with his face covered by clothing on the line and a still brighter light. The child climbs a box wrapped in a tarp, on her way to the sky, and rests in freshly fallen leaves, on her way to the earth. A dog paws in "moon mud." I have no idea how far the family lived from civilization as we know it, in two years in Rhode Island and Maine, or how the girl found such a small turtle, but they can claim the proximity of a backyard and the depth of the woods. Toy boats float in an outdoor wooden hot tub, as if on the edge of the wilderness.

The photographer's side of the magic act amounts to long and multiple exposures. They pick out the texture and color of leaves—or of the fur that the girl holds out like a magician's cape. They cover her with the stars and leave her transparent to the night. They allow Alario five copies of himself at the clothesline. He is up to his old tricks in a digital age, but he is not looking back. Children grow up quickly, and the old magic may soon be gone.

Learn your lesson

Christopher Williams teaches photography in Düsseldorf, and he is not above the basics. His latest project alone has lessons on consumer goods, like unwrapped chocolates, and the threading diagram for a machine. It shows hands loading film and changing shutter speed, the proper grip of a light meter pointing the wrong way as a model tumbles upside-down in a blur, and vintage cameras sliced right through to reveal or destroy their workings. It specifies manufacturers, models, dates, specs, and serial numbers, in titles that are clearly not going out over Twitter. It throws in a language lesson, for the actual series title is in French. And then there are the multiple lessons within a photograph.

In perhaps the best known, a nude poses against a black background, beside a Kodak Three-Point Reflection Guide. Only her name hints at her ethnicity, otherwise obscured by makeup, towels wrapping her breast and hair, and an over-the-top smile. Meiko is surely selling something, but what? Is it Eastman Kodak's technology (©1968), luxury towels, or photography as art? Williams is not saying, just as his titles spell out everything but what you wanted to know. For the uninitiated, a reflection guide helps with displays a gray scale and color scale to enable color corrections in proof, before someone remembers to crop it out.

Learn your lesson. Williams insists on it, even as he obscures the very possibility. Born in 1956, he studied at CalArts with John Baldessari, lived through Pop Art and the "Pictures generation," moved to the country of Bertolt Brecht, and calls his MoMA retrospective "The Production Line of Happiness" after a documentary by Jean-Luc Godard. (This has been a good month for Godard, who also supplies the title "Here and Elsewhere" for art of the Arab lands at the New Museum.) His father worked in Hollywood on special effects. As with that ambiguous sales pitch, any of these could support an interpretation, if you dare.

Should you treat this work as conceptual art? Williams began with such exercises as selections from government archives, each with the same arbitrary date and each with a view of President Kennedy from the rear. Whether the pose is presidential or an anticipation of death is up to you. Of course, this is California conceptualism, and Williams is not above a downright innocent enthusiasm. How come, he asks, models in "serious" photography never get to laugh like Meiko? Or think of it all as appropriation, from archival photographs to product imagery—and he has a habit of hiring commercial photographers to do the job for him.

A Brechtian detachment appears in the riddles, but also the assault on capitalism and the West. A series from the 1990s, "Die Welt ist schön (The world is beautiful)," features scenes of constructed beauty, like a beach in Cuba, and constructed terror, like a beetle trained to simulate its own death. A man holding a camera could be an advertisement, except that young African men do not often get to do the selling. If a Renault flipped on its side makes you think of the 1968 Paris riots or the automobile wreckage in Godard's Weekend, you are ready for the next lesson. Yet nothing has Godard's passionate astonishment. This is a Brecht for deadpan Californians.

Rather than wall labels, Williams insists on a checklist, more or less chronological (unlike the exhibition), accompanied by a map, more or less accurate. Enlarged fragments of a checklist also line the walls outside, with tiny numbers (starting with 1 for A) hovering like tools for font design. The curators, Roxana Marcoci with Matthew S. Witkovsky of the Art Institute of Chicago and Mark Godfrey of the Tate, smuggle inside still more walls—with one in bare concrete, as if for a potential future. Is the jumbled, low-hung layout retelling the photographer's favorite stories, refocusing the exhibition as about itself, or just keeping you at an infuriating distance? Do not be surprised if numbers on the checklist fail to add up.

Laura Larson ran at Lennon, Weinberg through September 13, 2014, Scott Alario at Kristen Lorello through July 18, and Christopher Williams at The Museum of Modern Art through November 2. Alario returned at his gallery's second home through March 26, 2022.