Has Bushwick Settled Down?

John Haberin New York City

Bushwick Open Studios 2012

Charles Atlas and Systemic Risk

If the prospect of "Bushwick Basel" did not have you annoyed or intimidated, you probably work in Brooklyn. In fact, you probably opened your studio that first weekend in June, along with five hundred others. (A related article tracks the growth of Bushwick Open Studios and the fate of alternative spaces through four earlier years, and I return again to Bushwick Open Studios for 2013.)

And almost dead center, just west of Maria Hernandez Park, a dozen galleries created a kind of hub among hubs—along, of course, with a message. We, the mini-fair seemed to say, are nothing like the corrupt art world of Miami Basel. Then again, we are every bit its equal, with a scope and independence the art fairs can only envy. Either way, who needs them? One can find a good dozen galleries in one building alone, on Bogart Street. At least half a dozen more lie only blocks away, not to mention the neighborhood's one famous restaurant, Roberta's.

Only a cynic could resist looking to the new year for new beginnings, and what better place to look than Bushwick? That is just where I found myself on New Year's Day—and in a new gallery to boot, Storefront Bushwick. The abstract painters there might even be said to live on border lines. NURTUREart had just moved to that one-time warehouse on Bogart Street. More were on their way, like Slag and Momenta. Yet some of the most promising signs were oddly familiar, and so was the tension between change and tradition.

It became that much tenser when one of Manhattan's brightest lights opened a branch, with Charles Atlas and a light show. Maybe Luhring Augustine took a huge risk by coming to Brooklyn, or maybe not, but its neighbors agonized more over the risk to them. Had they made it at last, and had the blocks around the Morgan Avenue stop finally reached critical mass? Or was one of Chelsea's most upscale galleries pushing them out? Is entering the mainstream itself a threat? With Bushwick Open Studios 2012, is Bushwick finally settling—or settling down?

Join the crowd

As for settling down, some of it is geographical. Some, too, is a very real sense of community, and one could see both at work in Bushwick Open Studios. One might start with a newcomer, Airplane, in a frame house on the western edge, where Andrea Burgay's light-toned abstraction and Shinya Watanabe's photographs of sunlight competed with ill-tempered robots from Tim Belknap and Peter Caine. To the east, one might end up in an imposing former factory across the border into Queens, for Parallel Arts and for Regina Rex, with its large abstractions by Britta Deardorff, Jackie Gendel, Juan Gomez and Eric Sall—one part Henri Matisse and The Red Studio, one part Marsden Hartley, and two parts in your face. In between, NURTUREart joined with Studio 10 in displaying Meg Hitchcock, who reconstructs sacred texts with a knife, as inner visions that William Blake would have understood. In also moving to Bogart Street, from the south Slope, Robert Henry displays intricate but regular patterning in two and three dimensions by Andrew Zarou, who just appeared in a group show at Parallel Arts.

If all that sounds vibrant or incestuous, it is both. It invites a one-weekend party scene that, for all its disdain of commerce, would have been unthinkable on a Chelsea art walk just fifteen years ago—and do not even ask about Soho before 1980. It leads to an echo chamber, in which dealers and free local papers get to assure one another they matter. It can leave even mainstream critics desperate to find, or to create, the latest scene. Both The Times and The New Criterion dropped word of events. They also both pointed to Deborah Brown, by now so busy that she could no longer open her studio.

Brown's tiny gallery, Storefront Bushwick, found room again for several artists, but mostly Abdolrea Aminlari. His gilded threads on paper have the lightness of leaves or lute strings. The month before, it displayed Carol Salmanson, an artist on the board of NURTUREartn (and the month before that, two artists who were then set to appear in June at Theodore:Art). In the mini-fair, Storefront had Adam Parker Smith's conceptualist vaginas. Along with Lesley Heller, who exhibits her paintings on the Lower East Side, Brown curated low-key sculpture at the Onderdonk House, a historic site again just across the border into Queens. And a healthy walk northeast of Bogart Street, Active Space gave her a solo show as well.

They are feeding off one another, but they are also thinking the unthinkable for populist Bushwick, curating. For its annual video fest, NURTUREart unfolded nine tales, most near floor level, in slow motion.  Patrik Qvist's stepladder onto the ocean, Marco Strappato's jogger, Michael Iauch's breathing in the earth, Janne Höltermann's revolving office door—they could all be out to reconcile Brooklyn lives with the rhythms of nature. Somehow even English Kills and Norte Maar permitted themselves solo shows, kitschy or not. The first had David Pappaceno's Venus of Willendorf in ceramics and ersatz tartans, the second posters by a local rock band, Pass Kontrol. At the mini-fair, Parallel Arts, too, chose a solo act, in Clinton King's hasty, colorful geometry.

Patrik Qvist's stepladder onto the ocean, Marco Strappato's jogger, Michael Iauch's breathing in the earth, Janne Höltermann's revolving office door—they could all be out to reconcile Brooklyn lives with the rhythms of nature. Somehow even English Kills and Norte Maar permitted themselves solo shows, kitschy or not. The first had David Pappaceno's Venus of Willendorf in ceramics and ersatz tartans, the second posters by a local rock band, Pass Kontrol. At the mini-fair, Parallel Arts, too, chose a solo act, in Clinton King's hasty, colorful geometry.

Naturally even solo acts come Bushwick style. They may come tongue in cheek with full knowledge of "the system," like ancient Greeks fronting a bank, by Chelsea Knight for Momenta. More often, they come in paint and in earnest. And plenty of artists these days think that dealers are stacked against both, even dealers struggling to salvage art after Hurricane Sandy or Covid-19. That belief can lead to more tired formulas such as "virtual exhibitions" than the installations they despise. In short, it can lead to open studios.

I promised myself that the growing concentration would make life easier this year, especially with the L finally running. I promised to feel less obligated to go beyond galleries, but I must have peeked into a hundred others in over four hours. I could hardly resist, when studios share floors with galleries and small businesses. Brown's efforts to keep her work in the public eye tells more than one Brooklyn story. Her latest paintings focus on cars, abandoned to the streets or to tiered parking structures, in her intense, moody colors. It is a vision of a falling and rising borough—where one can find art, find friends, and go home exhausted.

Brooklyn beginnings

Art in Bushwick is all about new beginnings, at least in its own eyes. It still seems downright determined not to become one more entry point to gentrification and the art fairs from London to New York, like Williamsburg before it to the west. Where even East Village art grew out of a reasonably small but determined circle, Bushwick long made anything but a scene. It has been all about sprawl, in everything from geography to outsize group shows. If it has a hub, that has emerged not on mixed-race residential strips but converted manufacturing spaces, wide empty avenues, and narrow dead ends. On a cold evening, still without coordinated openings, it can seem dark indeed.

Could this New Year, though, months before open studios, have held the real beginning? On a sunny winter afternoon, one even had a choice of beginnings. Three quarters of a mile further out, Norte Maar epitomized the neighborhood's "do-it-yourself" esthetic. Curated by "Guilty / (NOT) Guilty" has only four talented artists—Ellen Letcher, Francesco Masci, Alfred Steiner, and Pablo Tauler—but one might never guess from the flurry of sketches and images in painting, ballpoint drawing, and photos ripped from everywhere. They spill across the Bushwick pioneer's ground-floor apartment, as if the dealer had asked thirty or forty of his nearest and dearest friends to stick a work anywhere on the walls. And that, too often for my taste, is still exactly what Brooklyn group shows tend to do.

Back at Storefront, one could make quite the opposite mistake. It had three artists, but one could easily imagine just one or two. Each works with flat but layered surfaces, completely covered with paint—and each uses geometry to play against the symmetry of the ground. They would not look out of place around 1970, when critics and aspiring artists worried ever so much about pure painting. Only instead of an epistemological question, formalism here becomes an entirely practical question about art and illusion: however is that done?

For Gary Petersen, for one, how could such off-kilter compositions seem so deliberate? His small paintings seem assembled from strips of colored tape on an off-white ground, in slightly off-kilter and incomplete squares and diamonds. But no, he has built those hard edges and abrasions the hard way, in paint. Halsey Hathaway takes them to a larger and more voluptuous scale, with curved fields whose muted colors clash ever so softly. Some soak into the canvas, becoming brighter close up. Others retain brush marks in a flat but palpable finish, almost the texture of a fabric collage.

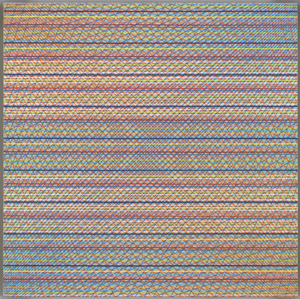

Edges for Rob de Oude edges are even more painstaking, but freehand—and, when it comes down to it, an illusion. His thin, mostly diagonal lines run nearly the breadth of his small paintings, most often in bright primary colors.  Wider diagonals and bursts of light ripple outward from the sheer overlap and juxtaposition. Imagine if Georges Seurat decided to copy Frank Stella and Agnes Martin. The results make an intriguing contrast with Robert Sagerman's dense, leaf-like splotches in Chelsea. His colors look squeezed right out of the tube, into DayGlo autumn foliage.

Wider diagonals and bursts of light ripple outward from the sheer overlap and juxtaposition. Imagine if Georges Seurat decided to copy Frank Stella and Agnes Martin. The results make an intriguing contrast with Robert Sagerman's dense, leaf-like splotches in Chelsea. His colors look squeezed right out of the tube, into DayGlo autumn foliage.

Then again, as new beginnings go, everything here seemed awfully familiar. Brown has simply reopened Storefront after her partner chose to concentrate full time on, yes, Norte Maar. She reflects a widespread revival of abstraction and its "geometric days." Even Hathaway comes close to so many others, like Suzan Frecon. NURTUREart has merely moved closer, to a block as bleak as ever that New Year's Day. The "neighborhood" still extends for miles and miles, as if Chelsea somehow encompassed Central Park.

Gambling on Bushwick

Could Bushwick, then, have gone nowhere fast—or has it finally settled down? If so, should a true Brooklyn artist celebrate or deem it sacrilege? No doubt artists have asked those questions, hopefully and expectantly, in year after year, just as when the Brooklyn Museum boasts of "Crossing Brooklyn." Yet in no time Luhring Augustine had opened its light show to the winter sky. And at least two newcomers to Bogart Street could enjoy the spillover. NURTUREart even called its engaging opening that winter night "Systemic Risk."

This group show seemed downright focused, in a neighborhood of collectives and chaos—with just four artists, a stated theme, and a large work at the center of the room. Still, it was Bushwick, and I could not swear what Daniel Behar's photos have in common with risk, rather than with Brooklyn slackers, and I could not swear what Sujin Lee's animation of a turtle means at all. Even the clear risks were comic and low key. Risa Puno's tilt-table game invites two players to keep their balls from falling into any number of holes in two identical labyrinths, one black and one white, and of course they fail. Along the L train, competition is still friendly, and cooperation still has its limits. Laura Napier's videos invite people to create their own critical mass, in order to cross safely without a stop light, apparently the only recourse for pedestrians in India.

Back outside, I had more to worry about than oncoming traffic. First, though, I had my first visit to Theodore:Art down the hall, where the risks were subtle and the rewards were clear. Dana Bell's colorful schematic figures wring their hands in private anxieties. Alasdair Duncan gives much the same treatment to masks, somewhere between color-field painting and cartoon versions of Paul Klee. Don Voisine is still more abstract, with his black diagonals wedged between colored horizontals, but the crosses become a sign language—as in a show last summer, "The Ghost in the Machine." What could come off as forced pairings instead do what a small group show should do, in reframing images and drawing connections.

Was their wealthy new neighbor taking a big gamble? As Stephane Mallarmé wrote, a throw of the dice will never abolish chance. And Charles Atlas bases his entire show on random numbers. He projects them in white, like Sol LeWitt wall paintings in perpetual motion. Here LeWitt's simple, text-based rules and assistants have become quantitative and automated. One work even starts with a Minimalist grid, like much in the LeWitt collection, covering a gently raised floor and drop ceiling as well as three walls, like an open cage.

Then numbers start to fill the spaces, while smaller signs fly across a second alcove, for Painting by Numbers, like constellations. At one point, they enter a large zero, playing with changing scales in empty space. The third and largest projection consists simply of six numbers, like the ID for an unannounced suspect. As a vertical bar creeps down the long wall and crosses a number, it changes. Each work offers a form of entrapment, and each promises a dazzling openness. Atlas calls the longest work The Illusion of Democracy, but his art delights in illusion and allusion, like that of Joseph Zito, as a kind of Neo-Minimalism or rebuilding Minimalism.

When the curator of "Systemic Risk," Jonathan Durham, speaks of "a transition to a less optimal equilibrium" as "inevitable and often irreversible," he could be offering a parable about art, life, or the neighborhood. Maybe it is too soon to fear gentrification. Sperone Westwater, Salon 94, and Lehmann Maupin still feel like invaders to the Lower East Side—but they had joined the New Museum, a mature gallery scene, and no end of restaurants. That Friday, I stumbled into darkness. Signs of life in the distance made Luhring Augustine's entrance a welcoming retreat. Opening with a light show makes perfect sense, and who is to call it settling down?

Bushwick Open Studios for 2012 ran the weekend of June 1. Related articles track the Bushwick annual event through previous years and in 2013. Gary Petersen, Halsey Hathaway, and Rob de Oude ran at Storefront Bushwick through February 5, 2012, four artists at Norte Maar through January 29, Robert Sagerman at Margaret Thatcher through February 11, Charles Atlas at Luhring Augustine through July 15, 2012, "Systemic Risk" at NURTUREart through March 16, and Dana Bell, Alasdair Duncan, and Don Voisine at Theodore:Art through March 3.