Panoramas of New York City

John Haberin New York City

The Grand Concourse and the Queens Museum

Most New Yorkers will never see the Grand Concourse, unless on the way to Yankee Stadium. And if they so much as set foot on the old World's Fair grounds in Flushing Meadows, they are probably Mets fans.

They are missing something, though. They are missing an architectural record of at least four generations. They are also missing glorious art deco details, the spaces where others were swept away, and the vital street life that has sprung from the desolation.

For me, the ghosts of New York will never clear. On a return to the Queens Museum, I find quite another panorama of New York City. I had not seen its more than nine thousand square feet since the 1964 World's Fair. By the time I returned, my father had died three years before. As a postscript, when the Queens Museum of Art dropped the part about "art," was it trying to tell us something? I am afraid so, and as its new name for fall 2013 comes with new architecture to match.

Forget the Bronx

Paintings and photographs preserve the past, even as they darken and fade. With architecture, forgetting and remembering are human actions on a grand scale.

People will always build and mock memorials, but architecture is different. Here conservation and attribution are not museum artistry hidden from public view, but the work of community groups or entrepreneurs. Destruction is not just the work of time, but abandonment, exploitation, and "urban renewal." And stasis is neglect. All sides have an interest in forgetting the turnover of human lives, in the present. They have a lot to forget.

There you go. I just fell into grand abstractions myself. New York will do that to you. I had been meaning to walk the Bronx in search of art deco masterpieces, but what one really sees is the frighteningly slow or rapid pace of change. In real-estate terms, a once-vibrant Jewish community vanished in the blink of an eye, thanks to a world war, generational change, upward mobility, and despair. Ever since, one can spend a long time looking for signs of change and signs of hope. More Brooklyn neighborhoods have turned over in those years than I care to say.

It is easy enough to slip into lobbies, like Jacob M. Felson's Fish Building at 1150 Grand Concourse. Just ask. These are not doorman buildings. A woman chastised a maintenance worker for letting me slip past. Then she smiled and asked me if I liked it. She was proud of having lived there for thirty-one years.

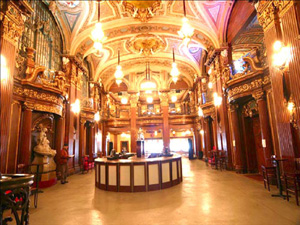

I should have told her that she must have lived there as a child. And she should be proud. She has survived, and the Fish Building went through landmark hearings the summer I visited. I could also have run on about the painted shields on its elevator doors, the abstractions nearby, or the aquarium mosaic outside that earned the building its name. Further north, Loew's Paradise may no longer show movies, but its gilded ceilings, carved doorways, lobby statuary, and sweeping stage must make a thrilling backdrop to concerts. More often, though, buildings have been stripped bare, from apartment façades to life itself.

A synagogue with its imposing pillars and portico has become a Seventh Day Adventist temple. Another synagogue has been absorbed into the Bronx Museum. A preposterous imitation of the Palazzo Farnese sits back from the street in midblock, at 166th Street, like an abandoned empire. If America once borrowed the Biblical image of a city on a hill, this is a small hill indeed. One mural at the Fish building could sum up the Bronx all by itself. Beneficent gods and swans sit with their backs to a dying or transcendent Jesus, and it is not easy to decide which.

Barreling through

Forgetting is easy. Not even the AiA Guide records who made those tiles—or the quaintly pastoral mural, bearing a quote from Joyce Kilmer, in the lobby at 910 Grand Concourse. Architects like Felson, Horace Ginsbern, or William Hohauser mean little now. Emory Roth did his best elsewhere, with the San Remo and Beresford on Central Park West. His compass-like lobby at 888 Grand Concourse looks cramped and dark. The Concourse thrived on mass anyway, at least as much as the details.

The boulevard earns its impact from its width and relative uniformity. Buildings often play curved edges against straight ones and slanted windows, in block-like apartment towers less than ten stories tall. Louis Risse, a French civil engineer, got the idea in 1891, and it came to completion in 1914. The architecture began to take shape only in 1928, and construction ended about a decade later. The style may not make it into a history of architecture, only a history of New York. It defines a neighborhood, just as the rusticated brownstones of the Upper West Side contrast with the cleaner or more ornate Upper East Side.

As for memorials, one has the restored Lorelei fountain in Joyce Kilmer Park. Or one can just look up, as architecture insists. Besides, I prefer the hulking pink marble monuments across the way, on the terrace of the old Bronx County Courthouse at 161st Street. Depression-era realism loved bulky groups, with human labor as both majestic and entrapped. Ben Shahn and his wife put the same mixed feelings into his murals for the General Post Office at 149th Street. Workers strive, triumph, and lay down the law of solidarity along with Moses, but they can never break free of tight spaces and row after row of their product.

Shahn's paintings are said to have faded, but he was a lousy colorist anyway. In fact, the darker reds may add a glow. One may as well focus instead on layers of destruction. The Cross-Bronx Expressway barrels through, thanks to Robert Moses, starting in 1948. Architecture intrudes here and there with its own record of change. One building adds the Miami kitsch popular in the early 1960s, a Miami firm has clad the Bronx Museum in glass, and a hospital imitates Michael Graves on the cheap.

The old courthouse still has the best site. Rafael Viñoly added a much-praised replacement two blocks east, in 2005, but mostly it replaces the concentrated mass of marble with an endless mass of aluminum and glass. I can only hope from photos that it looks better at night. I walked from the foot of the avenue to Fordham Road. While the Concourse runs nearly two miles further, to Van Cortland Park, it is already a long, dreary way from 166th Street to Loew's. On the subway home, I could see the pit where Yankee Stadium stood since 1923.

So much has dissolved along the way into fiction. Bonfire of the Vanities or Howard Cosell's "Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning" quickly became callous substitutes for urban history. People forget. I should know, for my habit of summer walks goes back to exploring Central Park with my father. He grew up on the Grand Concourse, somewhere near Yankee Stadium. I no longer know where.

A small world after all

On leaving the Queens Museum of Art, I had another glimpse of the past. Cordoned off, at the end of a long ramp, rests a replica of the Pietà. Michelangelo might have gotten lost on the way from Corona. I almost did—past the soccer players, rockets and miniature golf outside the Hall of Science, and wildlife hidden behind the fence of the Queens zoo. Maybe I was bound to get lost. I was looking for myself nearly forty-five years before.

For a nine-year-old in New York, the World's Fair was one big amusement park, the successor to Freedomland in the Bronx. How often and patiently my father took me there, and where is my patience now? Leaving the museum, I looked for traces of us both. To the west I could see the fair's heliport, now a restaurant, and to the south Philip Johnson's New York State Pavilion. Even at the time, its circular plaza, flanked by observation decks on stilts, looked painfully empty. Now crossed by only a thick wire canopy, it lies in ruins.

Museums are supposed to connect people to the past. The replica of the Pietà arrived as a kind of body double, for fear of theft or damage to the original, which made its trip to the 1964 World's Fair. Even before today's museum blockbusters, thousands took the moving sidewalk at the Vatican Pavilion for their moment in history. I had no interest in art then, but I shared the excitement. As kids will, though, I came for the future, like GM's Futurama II and Walt Disney's "Magic Skyway" for Ford. Who knew that Detroit's next century would mean cash for clunkers?

Museums are supposed to connect people to the past. The replica of the Pietà arrived as a kind of body double, for fear of theft or damage to the original, which made its trip to the 1964 World's Fair. Even before today's museum blockbusters, thousands took the moving sidewalk at the Vatican Pavilion for their moment in history. I had no interest in art then, but I shared the excitement. As kids will, though, I came for the future, like GM's Futurama II and Walt Disney's "Magic Skyway" for Ford. Who knew that Detroit's next century would mean cash for clunkers?

If all museums display the past, this museum's past is very much its own. Where the Met turns its back on Central Park, the Queens Museum belongs inside and out to Flushing Meadows–Corona Park. Before barreling through the Bronx, Robert Moses commissioned its heavy stone walls, modernist lack of ornament, and spindly classical columns for the 1939 World's Fair. It served again as the New York City Pavilion in 1964 (still an issue for Charisse Pearlina Weston today). Along with contemporary art, it holds mostly souvenirs—like an IBM Selectric typewriter or dinosaurs from the Sinclair Oil Pavilion. Its glory, also left over from the fair, is an enormous scale model of the city.

Coming to the panorama from the main floor, one overlooks Manhattan's Upper West Side, something a more modest model by Christina Lihan never reached, and it is fun picking out familiar landmarks from among its nine hundred thousand pieces. So what if I never found my high school or first apartment building? This version of New York real estate had its last major overhaul in 1994, and here the Twin Towers still stand. Every so often the lights dim, for sunset and sunrise over Central Park. New Yorkers will take special pleasure, too, in seeing New Jersey entirely grayed out. One has the same sense of freedom and control as in walking the streets of the city.

The control part lasts only a minute. Rafael Viñoly, the same architect who remade the Bronx courthouse, designed the ramp as a simulated helicopter ride. Heading up to the mezzanine, one passes the far edge of five boroughs. Before long the city itself takes over, and Staten Island alone extends further than I ever imagined. Before long, too, the city hovers in that space between past and present. Coming back to earth, I might have found myself in either one, wondering where else I could go.

Postscript: a museum after art

Four years later, a renovation roughly doubles the space for exhibitions, if not solely for art. Now six rooms wind around an atrium—enough for the museum's collection of Tiffany glass, memories of two world's fairs and a community theater, and three shows of art. The atrium does its own share of winding as well. One must squeeze past a curving wall to catch a handful of artists in residence. Or one can forget the whole thing and head straight for the museum's permanent wonder, that scale model. Grimshaw architects have altered its room, too, with an added glass panel and entrance stair facing the atrium.

This is about access. The Queens Museum has aimed not for esthetics but community. If visitors never so much as leave the atrium, fine with the museum. On opening weekend, a marching band accompanied me inside, much of it in costume, and a mariachi band played as I left. An alcove behind the curved wall held a ping-pong table, with (a sign promised) games to resume at 3. The family crowd included few Brooklyn hipsters, although the scale model has become frozen in time when gentrification set in.

Temporary exhibitions, too, insist on community. The Queens International has the borough's ethnic diversity built into its name, and the local artists have roots from Asia to Israel, while a few guests have made it in from Taiwan. This biennial looks more like a high-school art fair, although some artists add creative reminders of Queens—like Zeynab Izadyar, whose rotating dials have more to do with flight paths than the time, or Matthew Volz, whose actual clocks give each borough its own time zone. Pedro Reyes, a Mexican artist, promises to hold a People's UN (to make a pUN) in the atrium, with plywood cartons as seating. Bread and Puppet Theater long made populism its theme, and Peter Schumann introduces its actors in a smeared black and white, as somewhere between plain folk, monsters, and victims. In his Shatter Worlds, they cover plaster casts, that huge curving wall, a "chapel," and a "library."

Expansion may have come at the expense of a skating rink, but every element speaks to its place in the park. One can now enter from either side—by the Unisphere from the 1964 World's Fair, already a symbol of global unity, or closer to the nearest subway, if nearest means all that much after half a mile. That entrance also faces the parking lot and Grand Central Parkway's brutal cut through the park. The architects have clad that side in opaque glass, covering the original square, flat columns from its days as the New York City Pavilion. (It also briefly housed the United Nations, before the organization found a home in Turtle Bay.) They treat the building as one more shiny object and a place to play.

They obliterate not just a style but a history. How strange to boast of pulling hundreds of objects out of storage while effacing the building. The exhibition spaces, too, seem designed more to overlook the atrium than to exhibit art. One could easily mistake their dull walls for movable partitions, but they actually reduce the museum's options. Before, it had space for a tall painting by Dorothea Rockburne, but also smaller rooms suited to photographs by Andrew Moore. Now one has only white boxes, narrow alcoves, and a theater that had better not expect many guests. Even the replica of the Pietà looks set aside for a long-overdue trash disposal.

If the architecture's failures recall the Brooklyn Museum, they should. There, too, a costly renovation hides the façade behind glass and steel, and there, too, exhibitions can become all too politically correct. And there, too, art and visitors alike may end up lost in the lobby—although wasted space and commercialism have also marred the New Museum, MoMA, the Morgan Library, plans for the Whitney, and much else by Renzo Piano. It is hard to address communities without market research, even if that means shunting art aside. I still cherish the Queens Museum for memories of an older New York, but I may not find them. Maybe for once a museum atrium has found a place for its neighbors, but not as much in the way of a museum or of architecture.

I first revisited the Queens Museum in August 2009. After expansion, the museum opened to the public October 9, 2013. The 2013 Queens International ran through January 19, 2014, Pedro Reyes and Peter Schumann through March 30. I walked the Grand Concourse in August 2010. The scale model of the city in Queens also plays a special role in "never built New York."