Poetry and Privilege

John Haberin New York City

Poetry and Patronage: The Laubespine-Villeroy Library

Barbara Wolff and the Book of Ruth

In 1580, Pierre de Ronsard wrote in praise of the Laubespine-Villeroy library. Open it to me, he pleaded, for "tant d'hôte étranger"—such a strange host or such a host of strangeness. Books are like that, Ronsard surely knew, as France's leading poet. So many strange encounters lie between their covers.

With "Poetry and Patronage," the Morgan Library displays first and foremost the library's fine bindings. It displays, too, the inner circle of the French court that made it possible. Just as much, though, it asks of them and the Renaissance how much they are strange or familiar today. The Renaissance asked much the same about the classical world that it claimed to bring back to life.  As a postscript, Barbara Wolff could be elevating her art or returning to her roots not long before at the Morgan, in illuminating the Book of Ruth. The possibilities unfold in the shape of an accordion book.

As a postscript, Barbara Wolff could be elevating her art or returning to her roots not long before at the Morgan, in illuminating the Book of Ruth. The possibilities unfold in the shape of an accordion book.

Fanfare for the common king

The Renaissance in France was Ronsard's world as much as anyone's. As late as the next century, Jean Racine's stately tragedies can feel strange today compared to Shakespeare. Yet Ronsard already wrote in modern French, give or take a few spelling conventions. (Pardon me if I have regularized it for you.) In his sonnets on lost love, his classicism seems more biting, terse, and modern still, and he had pride of place in the library. Even now, scholars know a contributor to its artistry as only the Ronsard binder.

He also, though, knew how to play the game. He wrote those dedicatory couplets to Nicolas de Villeroy, with "no equal under the vault of the heavens" and all that. He had found a patron in Claude III de Laubespine, who did the real work of compiling a library—and who passed it on to Madeleine, his sister, and Nicolas, her husband. Claude was the confidant of King Charles IX, just as his father had been and just as Nicolas became secretary of state. Claude made good money from the job and even more from marriage, and he poured it into his books. They show his erudition, but also, the Morgan says, a man's "wealth and taste." Any reference to "Sympathy for the Devil" and the Rolling Stones is purely coincidental.

Yet death shaped their every act. Charles ascended to the throne at age nine, and Claude died in 1570, at only twenty-five. Ronsard wrote his eulogy. A portrait from the workshop of François Clouet shows the boy king soon after his ascent, but already canny and reserved—with fur in his cap and sleeves as the sole trappings of royalty. (Clouet himself rendered Claude in chalk, and the Morgan blows up a reproduction on the exhibition walls, as a backdrop to his achievements.) It balances maturity and youth, luxury and restraint.

The bindings display the same virtues. They have their plush leather and intricate gilding, with curls that depart freely from a calculated symmetry. Other and finer binders are known only by the name of a workshop, that of Mahieu Aesop, or as favored by their patron, Jean Grolier. The effect today is a show of wealth and the decorative arts, with nary an author's name on the covers. (Remember that they did not have to catch a casual browser's eye in a bookstore or online, and Claude could be trusted to organize his library as he pleased.) Yet the patterns stop just short of flowers and other details from illuminated manuscripts, like the Morgan's own "pages of gold."

They were leaving the distractions of medieval art behind, in favor of a new discipline and a new learning, and their contents do the same. Authors include Xenophon, the creator of history, and Theocritus, that of the pastoral in poetry. Just as striking, though, they favor what was then the latest thing, like many a library or book review today. The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of Francesco Colonna amounts to a wild ride through ancient myths and his dreams. Ronsard prepared and revised his collective works for the occasion. And then comes one last twist, with contemporary authors who inhabit the past—like Jacopo Vignola, whose Five Orders of Architecture (with detailed illustrations) rests alongside Vitruvius on architecture among the classics.

They still have their "fanfare," as the gilding style is known today—although such scholarly labels as "primitive" and "empty" fanfare may not mean much to you or me. Mostly, though, they are setting forth a course for Europe. England's claims to France were becoming distant memories, and Charles could command a dynasty and a nation. He could also command a place in a multinational elite, and still other volumes in the library take up statecraft. You may associate the Medici princes with the Renaissance in Florence, but Catherine de' Medici was the power behind the throne for a time as queen mother. Poetry and patronage asserted privilege and power.

Unfolding Ruth

Long before the craft and creativity of today's book art, there was the illuminated manuscript. Did the Italian Renaissance come about because of the public bombshell of the Gates of Paradise and early Renaissance sculpture? The Northern Renaissance had its roots in privacy and in privilege with a Book of Hours and illuminating the "The Medieval Hunt." In turn, long before the graphic novel became fair game for adults, books and prints could serve as folk art. The barely literate could find solace and guidance in the Medieval Housebook or a chapbook. Some even call the Crusader Bible the Morgan Picture Bible, like a child's picture book.

The Morgan has dedicated itself to both histories, although luxury most often wins out over a popular art. One can feel it just entering J. P. Morgan's library (enough for it to have its imitation in the New York Public Library). Still, a show upstairs stresses the appeal of woodcuts to Alfred Jarry, as akin to his own performances on behalf of the people. And Barbara Wolff has literally two sides to her artist's book and book art, in Hebrew and in English. She also has two sides in its elegance and accessibility. The curator, Roger S. Wieck, illuminates them with twelve medieval works from the collection.

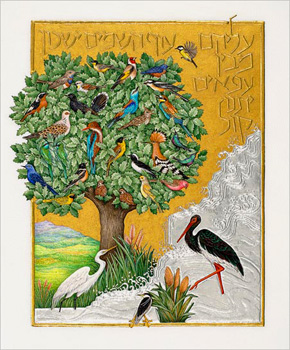

More and more, the Morgan has staked its future on contemporary art—part of a trend that has driven or torpedoed too many museum expansions. Wolff has shown here before, with "Hebrew Illumination for Our Time" in 2015. She then spent the next two years on the Joanna S. Rose Illuminated Book of Ruth, with calligraphy by Izzy Pludwinski.  As its name suggests, she worked on commission for a wealthy patron, who has donated it to the museum. Still, it could almost pass for a children's book without Beatrix Potter and her friendly rabbits. A child might enjoy simply unfolding the accordion.

As its name suggests, she worked on commission for a wealthy patron, who has donated it to the museum. Still, it could almost pass for a children's book without Beatrix Potter and her friendly rabbits. A child might enjoy simply unfolding the accordion.

A child could also appreciate its silent music. The eighteen-foot vellum gives its text plenty of white space, in black and a golden yellow, and the color illustrations on the Hebrew side have a winning simplicity. A bird's white wing unfolds against a hint of blue sky as the wing of god, while Ruth parts from Boaz at sunrise, in a pure landscape in much the same shape as the wing. If her placing herself at his feet in the biblical account has sexual overtones, Wolff leaves that to the grown-ups in the room. Other images convey Ruth's devotion in little more than the grain she reaped and the flowers she knew as perfume. Patience and pleasure appear, too, in the rewards of a sandal and wedding belt.

One can see her folk heritage at the Morgan, but also just how much has changed since the thirteenth century. Several bibles have only slim stacked illustrations on a page of small text, while the Crusader Bible has big blocks of flattened figures against flat colors. Either way, they are all about people and their acts—often paired and almost always gesturing. Wolff sticks instead to the objects that define their place in the story. (On the English side, she also sticks to black.) Even when Ruth embraces her mother-in-law, Naomi, the two women appear as little more than a bundle of linen.

The emphasis on things accords with material wealth, in a story about how Boaz, by marrying a widow, did his duty to keep her late husband's legacy in the family. The reticence of objects also accords with the multiplicity of contemporary interpretation. Ruth's sticking with her mother-in-law, accompanying her to Bethlehem from a foreign land, working in the field, and finding a new husband have been seen as selfless or as active—and the priority of two women together as a proto-feminism. (As it happens, the Crusader Bible is not really a bible, but rather a compendium of biblical stories of almost exclusively male heroes, but here it has room for Ruth.) She has a context, too, in the decisions facing Jews on their return from their Babylonian captivity in the sixth century BC, assuming they chose to return at all. Wolff extends the naturalism of her past work, with people few and far between, into the territory of immigration and exile today.

"Poetry and Patronage" ran at The Morgan Library through May 16, 2021, Barbara Wolff through October 4, 2020. A related review looks at Wolff and Jewish tradition.