The Passing Moment

John Haberin New York City

Photos from the National Gallery of Canada

Among Others: Photography and the Group

Don McCullin

In 1833, Henri Cartier-Bresson photographed a boy, head thrown back, feeling his way by hand along a wall. For that one decisive moment, a blind child has found transcendence.

Look, though, just to the left at the Morgan Library. Sixty years later, with Gary Schneider, another hand takes on a worn and peeling texture much like that wall. It suggests something gorgeous but precarious, even diseased, in art or life. Now look again, further to the right, where Man Ray uses a photogram to a very different end, that of Modernism. Cartier-Bresson's decisive moment has given way to "The Extended Moment,"  in photographs from the National Gallery of Canada. Group portraits from the Morgan's collection extend it further, as "Among Others," while Don McCullin finds the ultimate group portrait of an era in a war zone.

in photographs from the National Gallery of Canada. Group portraits from the Morgan's collection extend it further, as "Among Others," while Don McCullin finds the ultimate group portrait of an era in a war zone.

In my dreams, but only in my dreams, a lone individual can stop the guns. In my dreams, that is, and in photojournalism. The protester in a photograph by McCullin, seated right in the middle of a London street, confronts the Cuban missile crisis and the police bearing down. And they do stop, as if at a barricade, although their line extends well to either side. They are not going anywhere, but then neither is he. McCullin knew perfectly well, though, that the wars never stop and that heroes are hard to find.

The extended experiment

Is that it, then? Has photography's "decisive moment" (as opposed to "Time Management") passed, leaving only ghosts? Henri Cartier-Bresson took the term as the title of a 1952 book that itself became decisive. It summed up for him and an entire generation the meeting of photojournalism and art. And the National Gallery wants none of it. It comes closest to journalism with the damage to city hall right after the Paris Commune of 1871—but here it belongs less to the urgency of events than to early photography, Romanticism's love of ruins, and a tsk-tsk at working-class dreams of revolution. It is just one act in an extended moment from photography's origins to today.

Not that the Morgan's curator, Joel Smith, has in mind a history of photography or photography's last century. The show has little respect for chronology, genre, or subject. Nor is it just a matter of juxtapositions, striking as they are. A small daguerreotype of a nude, like a costume drama without the costumes, gives way to Richard Learoyd's large, vulnerable, and very real nude from 2013—and then to a badly dressed older woman in San Francisco, by Lisette Model in 1945. A golfer's swing in a motion study from Eadweard Muybridge leads to a chambered nautilus from Andreas Feininger, the spirals of a mechanical curve tracer from Konrad Cramer, and to outer space. A cannot stop at B before leading to C, D, and on to infinity.

Like Muybridge, they can extend the moment within a photo as well. After the show's most recognizable image, a mother in the Great Depression from Dorothea Lange, comes Alice Liddell—not as the girl from Wonderland for Lewis Carroll, but as a stylish young woman for Julia Margaret Cameron. After a mother and daughter as social types for August Sander comes first a suburban family for Joel Sternfeld and then an early photographer's personal family album. Still, the extended moment has a way of encompassing everything but its subject. Its juxtapositions amount to formalism. The extended moment has become a one-trick pony.

What then remains, and who gets to decide? What if that moment has always passed, by definition, and what if photography still thrills to its passing? (Geoff Dyer raises much the same questions in The Ongoing Moment—starting, in fact, with a blind person.) The Morgan does have a few decisive moments, like a man emerging from a pothole from Gordon Parks, a rural church from Walker Evans, an aerial mapping from Edward Burtynsky, and an interracial couple from Zanele Muholi half turning on the viewer and half turning away. It has the overwhelming darkness of Versailles at night for Edward Steichen and Prague at night for Josef Sudek. Does it have anything to add, though, about their artistry?

For one thing, it shows photography as an ongoing experiment, much as a daguerreotype or cyanotype was an experiment in chemistry. Not even Camille Corot, the Pre-Impressionist, could resist giving the medium a try. Practitioners took up x-rays and double exposures from the moment of their discovery, and as late as 2009 Alison Rossiter attained her silvery hues by moving a flashlight across light-sensitive paper. For another, the National Gallery of Canada takes its identity seriously. When in doubt, assume that an unfamiliar name is Canadian. Lynne Cohen, for one, composes with a deep red backdrop, in a show way short of color.

The selection does its best to avoid politics, context, or humanity. David Wojnarowicz and Alvin Baltrop lose their place in the AIDS crisis and their own private agony. It would rather pursue cleverness or beauty. Still, it probes the space between abstraction and naturalism—or, with Man Ray, between abstraction and Surrealism. If it feels awkward, the Morgan has had a photography department for only six years. How much it can pin its hopes on more than great books and old masters remains to be seen.

Trashing photography

Richard M. Nixon may have trashed the presidency, but at least he helped with the trash. His face appeared front and center on wastebaskets, amid those of past presidents. No lover of the latest dirt should have been without one, but is this a group portrait? The question comes up again and again in "Among Others." Subtitled "Photography and the Group," it does not exactly promise photographs of groups. Rather, it asks how people define themselves among others.

One might expect no less from the Morgan—and no more. Its exhibitions have as much to do with literature and history as art. Roy DeCarava contributes his photographs of African Americans, but for a book by Langston Hughes. Others mostly lost to history have captured a royal wedding (with a royal family that included Kaiser Wilhelm along with Queen Victoria) and Moscow after the death of Stalin. Soldiers and pilots came together as "living emblems" in two world wars.  Reduced to anonymity, in a tight mass viewed from overhead, they may not be the star of the show, but the darks and lights of their uniforms can still fashion a star.

Reduced to anonymity, in a tight mass viewed from overhead, they may not be the star of the show, but the darks and lights of their uniforms can still fashion a star.

One might expect no more and no less, too, in an age of selfies, and much here is no more professional and no less self-centered. Snapshots of human pyramids appear along with railway surgeons and a swimsuit competition. The curator, again Joel Smith, speaks of "photography's unique capacity to represent the bonds that unite people," and much is just as sunny and superficial. Looking for family tensions in photography by Jeff Wall, racial tensions in Parks, or psychic tensions in Diane Arbus? Look elsewhere. Peter Hujar, for all the blazing intimacy of his portraits, here works toward a recruitment poster for the Gay Liberation Front.

Is a poster a group portrait or even a photograph? What about postage stamps and baseball cards? Does it matter that an unknown photographer created the stamps from female private parts as works or art—or that Mike Mandel posed other photographers for his cards? Recently the International Center of Photography asked to see any number of genres as portrait photos. And here group photography can encompass street photography for Amy Arbus (Diane's daughter), The Americans by Robert Frank, and a collage of magazine clippings by Harry Callahan. More often, though, photographers here are out to construct the image of a nation through individuals.

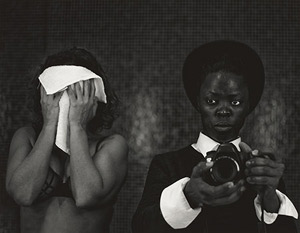

That image emerges only slowly from Hujar's contact sheets. Maybe a Beatles album cover would count as a group portrait, but Jean-Pierre Ducatez shot their lips alone, one at a time. (Seventeen magazine asked which one its readers would kiss, but they do not look inviting.) Richard Avedon assembles the players in an election year one by one, including not just the candidates, but also Rose Mary Woods. Marcia Resnick photographs others looking out on a landscape, making herself the sole point of connection. Eve Arnold shows a woman in training for civil rights activism, but one of just two behind her appears only through his hands.

Every so often, groups emerge from groups, Susan Meiselas pairs shots of performers and onlookers at a strip show. August Sander shows a family, but as part of his larger study of human types. Every so often, too, the definition of a community keeps changing. Art Kane brought a stellar lineup of jazz musicians to a stoop in Harlem, and then Rog and Bee Walker revisit the scene with just women. The frankness of Haiti for Danny Lyon turns up walls apart from Tunisia in a photo still under the influence of Eugène Delacroix. The show amounts to forced themes and lost opportunities, but nothing goes to waste.

Stopping the guns

Faced with Don McCullin, you are likely to think first of two other images entirely—by Jeff Widener of the Associated Press and Marc Riboud for Magnum Photos, the gold standard when it comes to photojournalism. In real life, China crushed protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, and Richard Nixon assumed the presidency and extended the Vietnam War for years. In the photos, though, an unidentified man will always stand inches from the tanks, and a girl will always extend a flower to bayonets on the Washington Mall. In each case, both the real outcome and the decisive moment are crucial to its success. They permit a photograph to testify simultaneously to brutality and to hope. For McCullin, though, both sides in a conflict have a share in its brutality, and their very hopes keep the horrors alive.

He looks into the faces of the police, who seem anything but pitiless, and at their dark but ragtag arrangement. He stands behind the faceless protestor, whose raised sign becomes one more blank. The photo's ongoing moment keeps the world forever on the brink of nuclear war, while its shallow focus sinks Big Ben and Whitehall Street in haze. McCullin grew up in London during the Blitz, and he became a kind of storm chaser in times of war, in Vietnam, Syria, Northern Ireland, and more. He knew the guns and the grenades, but also the long road to violence—in one photo, a road seemingly to infinity. It may be the closest he comes to finding peace.

Images of London's north and east end show people one step above poverty. They are shopping or struggling, but mostly just waiting in line. War, McCullin knows, is like that, too. An American in Vietnam holds the barrel of his rifle as if hanging on for dear life, in "shell shock." The term goes back to World War I, which cost artists, too, their sanity and their lives. McCullin, though, skips the blood to get right to the sweat and soil on the man's skin—and the terror, suspicion, or confusion in his eyes.

They do not make him a hero. If anything, he looks capable of killing the very next person he sees—maybe even the photographer or you. War here is not ennobling but isolating. Which side are you on? So politics once demanded in a more optimistic era, but here there is no answer. McCullin's love of highlights and shadows in black and white does not clarify things, but rather intensifies the human stain.

He avoids the worst clichés of photojournalism, just as he stops short of leaving photojournalism behind. For the newspapers these days, a refugee camp means a mother with her mouth wide open and a dead child in her lap, like a debased pietà. McCullin's anguished women appear instead among friends, oblivious to their comforts. A woman in the Mideast eyes where to throw her explosive, and a man with his weapon craws across an empty hotel, but group photos only intensify the horror. Gunmen prepare to torture their victim before killing him. A soldier taking refuge in a Vietnamese home makes the family album by his side a record of displacement.

This is not the overtly political photography of Danny Lyon—or the artistry and irony of Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand in America. McCullin does not so much disturb familiar feelings as intensify them. When he takes a break for more picturesque shots of ancient ruins, they might have fallen to the same battles. That may explain why he is less well known. The compendium of conflicts cuts close all the same. He knows just how hard it is to stop the guns.

Photographs from the National Gallery of Canada ran at The Morgan Library through May 26, 2019, "Among Others" through August 18. Don McCullin ran at Howard Greenberg through November 16.