Stillness and Light

John Haberin New York City

Lynn Umlauf, Mary Corse, and Dorothea Rockburne

Painting would not have staged a comeback for a new millennium if it had stayed the same. And the recovery of older artists and women would not have made sense if it told you what you already knew.

Sometimes, though, a healthy reminder will have to do. Lynn Umlauf and Mary Corse emerged on the east and west coasts around 1970, but they never really went away. They have never blended abstraction with boisterous or enigmatic imagery, although both have found inspiration in landscape and Umlauf in dance. They have not made hybrids of painting and new media, although Corse had to work her way out of sculpture. She also experimented with sources of light. They showed that they could make pale colors and fragile materials emerge before one's eyes as tokens of stillness and light.

Talk about crude oil. For Intersection, Dorothea Rockburne poured heating oil on a plastic sheet, from a roll only partly unfurled on the floor coming out from the wall. Even in a 2018 recreation at Dia:Beacon, the cracks are showing. Then she placed paper on top, to assert its geometry and, if only briefly, to interrupt the blackness. Is it an endnote or a continuation of the process? Is it a part of the wall or the floor?

Keep from being sculpture

Lynn Umlauf first exhibited back when painting was supposed to evoke nothing but itself. So naturally her work evokes its time. The gallery quotes an interview with David Shapiro, for Flash Art in 1977: "I want to take the sensuality out of my works and leave only the physicality." She could be describing a black painting by Frank Stella, Christopher Stout, or Tariku Shiferaw today with the unrelenting sheen of its house paint and the wood of his stretcher turned to jut more thickly in your face and off the wall. Her more recent sculpture presents a tangle of wire and metal like his later work as well, but with a color and clarity that he might envy.

Still, it is not so easy to separate the physical and the sensual, and Umlauf has the twists and turns of biomorphic abstraction. Born in 1942, she worked at the time in pastel and acrylic on paper glued to canvas. The seams show, and cut edges threaten to unravel before one's eyes. The collision between color and bare canvas approaches early shaped canvas for Elizabeth Murray. And the collision between pastel drawing and irregular outlines approaches gesture for Mel Bochner in the 1980s. Unstretched canvas can never fully identify itself with the wall at that, like the far more sculptural twists of Lynda Benglis, with their allusion to the body, fabric, and dance.

The work is sensual in another way, too, in its association of color with light. "I don't refer to air and space," she said in the interview. "I refer to light." Nor is it the artificial light of the gallery. Could it be the light of her studio on the Bowery or of Italy, which she loves? Painting might turn out to evoke something beyond itself after all.

The pale blues, reds, yellows, and greens might belong to the Italian countryside and its architecture, and Umlauf says that they remind her of fresco and terra cotta. Bare canvas becomes one more color among others. The colors become more pronounced on paper, which also reaches further off the wall. Cut and peeled back to allow more space for drawing, it brings out what is going on in the paintings as well. She includes four triangles and two trapezoids, leaping across the space of the gallery. Mostly, though, she manipulates a single shape on the wall—and only the color, she adds, will "keep it from being sculpture."

It is easy enough to extend the catalog of fellow painters, starting with Michael Goldberg, her husband up to his death in 2007. The identification of single colors with their support has a parallel in Brice Marden or Ellsworth Kelly. The use of lines and gradations to dissolve color into light recalls Agnes Martin. Umlauf has nothing like their lightness or their weight. Her very muteness makes her more of a painter's painter. But then painting was supposed to be about paint.

Paul Corio earns his gradations the hard way, shape by shape—but is it all a matter of chance? He, too, looks back to a more systematic time, in geometric abstraction. He says that he determines his shades based on the winning horses at a racetrack, found outcomes evident in divisions of a curve snaking its way around and across the canvas. A single blue takes over a pattern akin to old floor tiles that, from moment to moment, might appear to be receding into or projecting out from depth. A single tile becomes a color wheel grading into white. It recreates design, architecture, and the tools of a painter's trade through the daily rhythms of his work.

Subtlety and impact

No one goes to the art fairs for subtlety. Who has time? Artists know that they have to make an impact, like Mary Corse at the 2017 Armory Show. And she did, with a huge square on a still larger field. Still, she can never leave the subtlety behind. Both square and field, after all, were shades of white.

Few artists can "do" both subtlety and impact. Her last gallery show took on a second life only as one exited into bright sunlight, much as artificial light and collector impatience flattened her work at the fair. "A Survey in Light," at the Whitney, opens with a painting eight feet high and twenty feet long. As one moves across, its thirteen vertical bands become different combinations of from one to three grays and whites. One can see, too, the horizontal smears as she laid down acrylic and glass microspheres, as aspects of radiance, reflection, translucency, and matte. Associate the layers with figure and ground, but at your own risk.

Agnes Martin and Robert Ryman can do white on white as, respectively, subtlety and impact. Corse can do both, but not necessarily at once. That constant back and forth also sets her apart from Ad Reinhardt, with his demands for an emerging perception of black on black. It links her to California Light and Space artists like Doug Wheeler, with their use of such nontraditional materials as resin and marble dust, in sculpture and installation. Born in 1945, Corse studied at what was to become CalArts before settling in Topanga Canyon for a further exposure to landscapes and natural light. She is, though, always a painter.

The curators, Kim Conaty with Melinda Lang, see her as a painter of light, but they could just as well have called the retrospective a survey in materials. On film, Corse stresses the determined craft of laying those materials down. Craft also takes a learning curve, and she studied enough physics to incorporate Tesla coils as an additional source of energy and light. One can narrate her career in terms of changing materials at that. She starts in 1964 with shaped canvases governed by a physical frame and triangular white columns. As one circulates, they shift from painting to sculpture and back, while the band between them shifts from gray to the "negative space" of the viewer and the work.

The curators, Kim Conaty with Melinda Lang, see her as a painter of light, but they could just as well have called the retrospective a survey in materials. On film, Corse stresses the determined craft of laying those materials down. Craft also takes a learning curve, and she studied enough physics to incorporate Tesla coils as an additional source of energy and light. One can narrate her career in terms of changing materials at that. She starts in 1964 with shaped canvases governed by a physical frame and triangular white columns. As one circulates, they shift from painting to sculpture and back, while the band between them shifts from gray to the "negative space" of the viewer and the work.

Soon come small stacked planes of Plexiglas and acrylic, light boxes with their blinking Tesla coils, and finally painted rectangles. Their geometry can include notched corners, symmetric verticals and horizontals, and at last the microspheres. A few works along the way incorporate black ceramics for a rippling surface evocative of water or mud. They incorporate an additional source of light and space in the museum. Now and then they incorporate the viewer's shadow as well. They unfold on an increasingly large scale, so that just two dozen works add up to a lifetime.

One can see them as progressive discovery, right and wrong turns, or continued experiment. One can see them, too, in terms of the back and forth. Their polar opposites are apparent in that opening mural from 2003. It is about figure and ground, flatness and depth, light and space, motion and stillness, optics and materials, industrial parts and the artist's hand, vertical and horizontal, left and right, shades of white and shades of gray. Titles also mention black light and black earth, and she often sets work in pairs. One might go to her more celebrated peers for subtlety or impact, but one can go to her for the dualities.

Not so crude oil

To choose between opposites for Dorothea Rockburne, one would have to place the work once and for all as painting or sculpture, and nothing about Rockburne is as crude as may appear. You may remember her most, in fact, for an exercise in lightness. She folded and unfolded paper, letting the creases and their shadows take care of the design. Make that some of it, for she added pencil, oil, and aquatint to each of five sheets, along with an etched X at their centers. In a photograph, areas above or below a fold take on a deeper contrast, but still in shades of gray. Even in person, you may never know where printing or drawing begins or ends, but you can hardly help knowing that the folds define X's as well.

They are among just six works from around 1970 at Dia:Beacon. While Dia prefers her dark side, it shows her as both massive and meditative. One can see her there in context of another crude performer, Richard Serra, but free of his calculated aggression. One can see her on the way to Robert Ryman, between materials and surface, but with more than white beneath her white.  One can see her, too, after literal light shows by Robert Irwin, Dan Flavin, and François Morellet, but with her hand in everything. Morellet sets his neon fixtures at regular intervals, on the floor of a cavernous dark room, like a mine field. (For the work's protection and not yours, a guard tells you where to walk.)

One can see her, too, after literal light shows by Robert Irwin, Dan Flavin, and François Morellet, but with her hand in everything. Morellet sets his neon fixtures at regular intervals, on the floor of a cavernous dark room, like a mine field. (For the work's protection and not yours, a guard tells you where to walk.)

Born in 1932 in Montreal, Rockburne took an interest in Egyptian art, astronomy, and mathematics, as predecessors in order and eternity. Algorithms in math surely influence her recipes for a work's production—just as for an early Adrian Piper or Sol LeWitt. Yet she passed through Black Mountain College as well, like Robert Rauschenberg, and its esthetic of chance and the ephemeral. She worked with the Judson dance company, and the white sheets hang high on the wall, as if in flight. She also grew close to Carolee Schneemann, who knows a thing or two about crude materials in performance. With that plastic on the floor, she leaves unstained areas to either side of the blackness, and the cracks sparkle—just as Tropical Tan leaves fields of bare steel above and below her tan paint's wrinkled finish.

Dia shies away from her mathematical rigor or later paintings of the heavens. (I have gathered earlier reviews elsewhere, for a fuller account.) It includes Domain of the Variable on the scale of a gallery, with peeling chipboard to one side and grease to another. Rockburne left it to cook, as she put it, for the show's rare touch of color. A horizontal crack in cement unites the four walls while bringing out the contrasts. She reinforces the line in charcoal as it runs through the projections into the room.

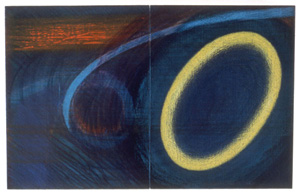

Cooking makes perfect sense for such fiery colors. Red washes into yellow and reddish brown into purple. They take her closer to painting, but also to earthworks, much like color for Michelle Stuart a few rooms away. Stuart's 1976 Sayreville Strata Quartet derives from her work with the Army Corps of Engineers. Her tall rubbings take their colors and textures from an abandoned brick quarry in New Jersey. Like Rockburne on paper, they also blur the distinction between drawing and materials. The association of the earth with its strata hints at process in her art, while quartet links the layers of earth and art alike with mathematics and music.

For Rockburne as well, the sides of her art come together in person and in time. She even connects the two parts of her Set with a plus sign. There, too, crude oil, tar, and peeling add up to a clear but unstable geometry. The two sides run together more plainly still with Ineinander Group, where two rows of paper progress from dark stains to creased white. When I photographed a work by Corse just one room away, the black ceramic appeared as mottled brown on white, thanks to reflected light. With artists like these, Minimalism can be crude, but never just black and white.

Lynn Umlauf ran at Zürcher through June 30, 2018, Paul Corio at McKenzie through April 29, and Mary Corse at The Whitney Museum of American Art through November 25. The shows of Dorothea Rockburne and Michelle Stuart are temporary but ongoing at Dia:Beacon. Related articles tour later work by Rockburne and Dia:Beacon.