True to Art

John Haberin New York City

Ernst Haas, AND/ALSO, and Photography

Nothing Is So Humble: Prints from Everyday Objects

Early photography promised the unvarnished truth, when painting could promise only the varnish, the artistry, and the lies. Its faces still speak to the present from out of a distant past.

But are they, too, lying? Photography ever since has grappled with its claims to truth and to art. Ernst Haas made those claims vivid when he used color photography, still a novelty in art, to approach abstract painting. He knew all the same how much he was subverting media. Decades later, art is more likely to relish hybrid media, to the point that even abstraction can encompass almost anything. The photographers in "AND/ALSO" downright boast of all that they can "misrepresent," painting included.

No ideas but in things. Those words from William Carlos Williams came to speak for modern poetry, and they resonated in art long after, from Minimalism to this day. So is the solution to stick to the things themselves, or is it in still life that photography comes closest to abstraction? The dilemma extends to other works on paper as well. Now the Whitney makes a point of things, with prints from everyday objects. One might well mistake much of them for photography.

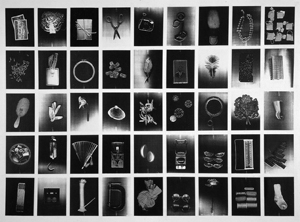

For all his relevance, Williams raises a stubborn question. He was, after all, a wordsmith, and "Patterson," where his words appear, is an epic poem. Can objects serve as a language—or supply its alphabet? They did for Pati Hill in the late 1970s, with what she terms an alphabet of forty-five prints. As their sheer number suggests, it is a rich one, with an exemplary tonal range and such things as razor blades (the old-fashioned kind), a vintage photograph, a hair brush, a fish, a fan, and a limp glove. The six other artists in "Nothing Is So Humble" add to her vocabulary lesson, with recent acquisitions in the museum's collection.

Photography's competence

Late Modernism had two lessons for photography, and unfortunately they disagreed completely. Remember a photograph—a flat, rectangular object employing chemicals to represent the world? Surely it could aspire to the same formal rigor as a painting, and it did. Berenice Abbott could see in architecture the darkness of its shadows, and Walker Evans could pin a woman's Yankee bone structure against the wood frames of a house. Who, then, would complain if others were pushing further, toward abstraction? Who could complain, too, if abstraction no longer meant painting?

On the other hand, as Greenberg put it, formalism demanded that each medium seek its "unique and proper area of competence." How then could photography settle for painting? By the 1990s, Postmodernism called abstraction dead, and appropriation propelled photography into mainstream galleries. A distrust of abstract photography could only deepen. Why should a photograph take its artistry and dignity from the very aura it had dispelled? Ernst Haas did as much as anyone in photography to dispel the aura.

Bruce Silverstein gallery keeps refreshing the history of photography and photography's last century, teaching me names I hardly knew, and it does so again. For Haas, it recreates a 1962 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. It shows him in the decade's slippery space between representation and abstraction or between photography and trompe l'oeil—and it shows that not as excessive refinement, but as lively experiments in a new medium. The Modern gambled on its first show of color photography, and that same year Barnett Newman was about to set aside his "area of competence," abstract painting, to make sculpture. So much for the purity of modern art history. Could "Remote Viewing," abstraction at the Whitney Museum overflowing boundaries in both media and imagery, have the last word after all?

Faced with color photography by Paul Outerbridge and William Eggleston before him, Haas fell in love with color all over again. At the same time, he returned to Modernism for its most impure impulse, collage. A large, irregular field of red could have come from Robert Motherwell, but Abstract Expressionist drawings rarely have the same depth on a scale this small. Impurity for comes with his subjects, too. I could make out two crushed soda cans, enough to wonder where and how they arose. I enjoyed just as much my inability firmly to decipher much else.

Haas is always ready to play around with dogma, whether it identifies photography with documentation, formalism, or something in between. He also took stop-action photographs of athletes, as still more shattered fragments of nature and color. If that takes him closer to photojournalism or the movies, they seem remote indeed from Eadweard Muybridge. Anyone looking for a scientific analysis of motion had better look elsewhere. You may prefer the abstractions, but forget about solving the riddles of art and nature. You can still share in the play.

I wrote this in the present tense, because it was my present, too, but that look back is already fifteen years past. Now painting is no longer dominant or left for dead. And photography is again in play as an experimental medium. Digital techniques, the appropriation of reproductions, the severance of the photographic subject from any necessary space outside studio props—all these make it hard to recognize reality or abstraction. What goes around, comes around. Someone may well be appropriating this show right now and clicking the remote.

Photos of contamination

Early photographers relied on theatrical poses for their truths, like Lewis Carroll, and painterly conventions, like Alice Austen. They wanted to be taken seriously, and that was the way to go. And now that anything goes in art, crossing media has become all but second nature. Kate Shepherd, for one, can start with a studio photograph and with abstract painting. Just a block over in Chelsea, the limits of a medium are the point, in order to break them, but is it still photography? Or is it "AND/ALSO: Photography (Mis)represented"?

When I first caught Michele Abeles, in the 2015 Whitney Biennial, her contribution felt like a "boisterous painting." Would I call it boisterous now? Would I call it a painting? She is one of just six artists in a show of just thirteen works, all of them photographers but not one altogether content with the medium or the label. A show this small and this messy is all about setting and breaking limits. As its title has it, the choice between photography and art is not an "either/or," but an "and/also."

They may add a painterly touch in Photoshop, like Lucas Blalock, or with cardboard and paper cutouts, like Daniel Gordon. Erin O'Keefe studied architecture, until her architectural models and their photographs took on a life of their own. Roe Ethridge collects the work of others, but his handmade book and the wood cabinet on which it rests upstage them all. Even when the photographers do no more than train the camera on the scene before them, it cannot dismiss the evidence of things unseen. Seemingly gilded drapery for Farah Al Qasimi covers a kiosk in Chinese market in Dubai. It preserves the richness of two cultures, even as it attests to twenty-first century commodity culture, closure, and displacement.

Abeles spills out over the picture plane many times over in a single picture. One photograph shows a calendar waiting for someone to add a personal history by writing in appointments. It also contains a bath sandal that has lost its partner but retained its tacky plastic blue. The calendar seems to hang on a tiled wall, but the ceramic tiling is real, and so are the washes of color that cover it. Whoever created the month's illustration has covered up something as well, perhaps a naked body. This is and is not calendar art.

The breaking can come as a contamination. Blalock, who has appeared in shows of "The Photographic Object" and New Photography at MoMA, captures overflowing bookshelves in glorious sunlight, like the welcome to an ideal summer in an ideal home. And then he adds paint with the brush tool, like bacilli and lobster claws floating above. A desk piled with snail mail, with more daubs, similarly alludes to an analogue past and a disturbing present. Ethridge, senior enough to have shown in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, overlays his memorabilia on a pencil, defying the written and the artist's gesture. Whatever those lead-like strips are in that old cabinet, I would just as soon not know.

The show's title, punctuation run wild, signals a little too much postmodern contamination—or just a talented young curator, Chandler Allen, eager to share what she has learned. The press release speaks of "Surrealist pedagogy," "coded systems," and a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé that overruns the printed page. Still, theory has one thing right, the disturbing presence of the body, human or inhuman. In a second photograph by Abeles, scattered tiles come to the surface, over the image of what might be straw or human hair. When Al Qasimi photographs a bird in the hands of its trainer, its hood seems like cruel and unusual punishment. When Ethridge isolates a horse against a red background, it could be regal or afraid.

Crossing limits can take time, like crossing a physical threshold without the key. Some things insist on their distance and their chill. Gordon has an overflow of sensation, in still life. Why then do the vegetables appear so glossy or in silhouette? O'Keefe's wood and felt models concentrate their color and light, but they also squeeze urban design into two dimensions, in public spaces devoid of people. Could they have already departed, for a less certain future?

Ideas and things

"Nothing Is So Humble" has a modest lesson plan, on the floor for the Whitney's education department, and another artist, Sari Dienes, supplies the title as a poet herself. "Bones, lint, Styrofoam, banana skins, the squishes and squashes found on the street," she writes. "Nothing is so humble that it cannot be made into art." And that raises questions, too. What does it take to make everyday objects into art? Dienes skips the banana peels, in favor of ink rubbings of the street, including sidewalks, gratings, and manhole covers.

I do not mean to ask what is art, that tedious old question, but rather what is too arty? How much do these artists, as curated by Kim Conaty, have to transform objects and their images before they become art? Can art ever, in that startling vision of William Carlos Williams, allow things to be themselves? Pati Hill's objects look ever so real, but as spooky as photographic negatives. They are also now and forever in the past, thanks to her nostalgic choices and the brute fact of printmaking. She claims their transformation into musical instruments as well, with an egg slicer her harp.

Things take on a ghostly but ever so immediate white for Dienes, for whom the street becomes her picture plane. And then similar patterns and textures become abstraction for Kahlil Robert Irving, on a larger scale and with a startling intrusion of color. Virginia Overton feels Modernism's urge to abstraction, too, leaving me without a clue to a print's origins. Her beam in Socrates Sculpture Park for 2018 summer sculpture transformed Minimalism into a playground swing. Here her soft-ground etchings boast of neither purpose nor materials, only faint traces and a fragile beauty.

Things take on a ghostly but ever so immediate white for Dienes, for whom the street becomes her picture plane. And then similar patterns and textures become abstraction for Kahlil Robert Irving, on a larger scale and with a startling intrusion of color. Virginia Overton feels Modernism's urge to abstraction, too, leaving me without a clue to a print's origins. Her beam in Socrates Sculpture Park for 2018 summer sculpture transformed Minimalism into a playground swing. Here her soft-ground etchings boast of neither purpose nor materials, only faint traces and a fragile beauty.

With her sculpture in motion the year before, on a terrace of the Whitney, tall black windmills pumped air into tanks of aquatic plants. Was it an ecosystem to itself or a transformation of ecology into art? The artists raise the question with their processes as well. Apart from Overton, most avoid traditional printmaking in favor of pressing the things themselves up against a plate or glass—in what are called calligraphy and Xerography. Ruth Asawa carves a potato before using it as a stamp or as movable type. It, too, has a cryptic alphabet.

These techniques recall photograms, like the rayographs of Man Ray, who placed objects on photosensitive paper. They would fit right in with contemporary abstract photography. Even at their spookiest, though, they benefit from a print's belief in things. Zarina Hashmi, or simply Zarina, uses wood scraps as relief prints, echoing her materials in her image, of fencing in the round. If things here have become confining, Julia Phillips assigns confinement a gender. She stretches hosiery to the point of broad tears and gaping holes even before running it through a press.

Do objects, then, speak of life? In her wire sculpture, Asawa can sometimes suggest egg crates, and Zarina has used cut canvas as her Shadow House and black strips as a shorthand mapping of her travels. Phillips has also fashioned black ceramics into body parts, laying them beside a corkscrew and forceps. Are they household objects or instruments of torture? With prints, the artists can dial down the threat and dial up the sense of wonder. They can look for ideas in things.

Ernst Haas ran at Bruce Silverstein through June 11, 2005, "AND/ALSO" at Paul Kasmin through August 21, 2020, and "Nothing Is So Humble" at The Whitney Museum of American Art through April 18, 2021.