The Body at Day's End

John Haberin New York City

David Hammons and Around Day's End

For an artist so elusive, David Hammons has intrigued gallery after gallery and entered museum collections. For an artist so committed to irony, Hammons has also done more than anyone I know to confront visitors with the African American experience. And for an artist who has sold snowballs on the street, he has done it all with warmth and passion. Besides, he sold those snowballs in Harlem, in person and in the cold.

Any wonder, then, that he began by literally throwing himself into his work? True, his Body Prints went on view only years later, against his wishes. And sure, he has filled a maze of rooms with nothing but gallery-goers and pencils of dim blue light.  I have written about this and other shows, so I leave you to read more there. It helps, though, to see him now at the Drawing Center in something more like painting—and to see why he gave it up for what has since taken him to a pier along the Hudson and his Day's End. The Whitney also looks back to his inspiration in Gordon Matta-Clark and "Around Day's End"—but turn first to the backstory, in his Body Prints and blue light.

I have written about this and other shows, so I leave you to read more there. It helps, though, to see him now at the Drawing Center in something more like painting—and to see why he gave it up for what has since taken him to a pier along the Hudson and his Day's End. The Whitney also looks back to his inspiration in Gordon Matta-Clark and "Around Day's End"—but turn first to the backstory, in his Body Prints and blue light.

Wrapping himself in the flag

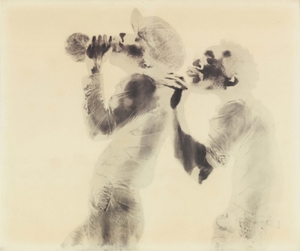

David Hammons landed in LA at age twenty, in 1963, and studied at the Otis Art Institute with Charles White. A strict realist, White may seem a strange choice. Yet Hammons took up drawing, too, with everything he had. Starting in 1968, he used his hands, but without a brush on the one hand or the childlike innocence of finger-paint on the other. He also led with his forehead, chin, and butt. Then, too, White painted The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy, a mural at Hampton College, and Hammons made his art a challenge to conventional views of American democracy.

Among the first Body Prints, he appears naked but for an American flag, his hands raised in prayer. He calls it Pray for America, but he could just as well be praying for his poor, gaunt African Americans self. The flag motif appears again and again. It cloaks him in red, white, and blue or in black and white. Another title speaks of him as a black man first and an American second, and he must have relished the irony of "wrapping himself in the flag." Protestors then were using that metaphor to criticize the phony patriotism of those demeaning civil rights and supporting the Vietnam War.

The flag is a portent, too. Hammons will create his own in the red, black, and green of the Pan-African Coalition, and a body print applies those same colors to a map of the United States. As another title has it, Close Your Eyes and See Black. It speaks, like his elusive later art, of the invisibility of African Americans to those who would just as soon not see. At the same time, he makes it clear that seeing is not believing. In reality, he is not even wearing the flag, which he adds as a screen print to the transfer print of his body.

Clothing, he knows, can create or delimit one's identity, as in fashion, and he also cloaks himself as a woman, as Sexy Sue. For all that, though, smearing his body with grease and pigment has a frightening immediacy. It lends him the ghostliness of a photographic negative or the skeletal reality of an x-ray. The question of visibility also appears as he leaves his greasy hand print on the glass of a door labeled Admissions Office. Blacks, he implies, can see in but cannot enter, while those inside may refuse to see out. For them, a black man is at best an enigma, and a screen print tosses in a jigsaw puzzle piece as well.

Hammons also incorporates a window shade, and he admired how Betye Saar the appropriation art of Robert Rauschenberg and combine painting to a black woman's ends. He could also think of the prints as performances, and he admired the black performance art of Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger, the dancer and sculptor, as well. One can see his selling snowballs later as one part anti-art and one part performance. After a group show of "100 Drawings," the Drawing Center leads, in fact, with that aspect of his work—photos of Hammons (with his pants on) applying himself to paper. For once, you can almost get to know him. He is having fun.

Hammons also incorporates a window shade, and he admired how Betye Saar the appropriation art of Robert Rauschenberg and combine painting to a black woman's ends. He could also think of the prints as performances, and he admired the black performance art of Senga Nengudi and Maren Hassinger, the dancer and sculptor, as well. One can see his selling snowballs later as one part anti-art and one part performance. After a group show of "100 Drawings," the Drawing Center leads, in fact, with that aspect of his work—photos of Hammons (with his pants on) applying himself to paper. For once, you can almost get to know him. He is having fun.

Not all is black in the prints either. He doubles himself, as The Wine Leading the Wine, and turns himself into a playing card, effectively calling a spade a spade. His nipples serve as the Itty Bitty Titty Committee. Yves Klein in France had rolled his body on canvas, but Hammons rejects Klein's associations of gesture with Abstract Expressionism. He is playing by his own rules. Still, by 1980 prints had started to look much like painting, and he had been spending more and more time in New York and on other things. He had exhibited at Just Above Midtown, the black-run gallery, and it was time to take what he had learned and to move on.

Pier review

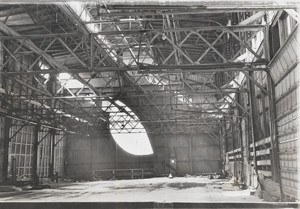

Decades after selling snowballs on the streets of New York, Hammons is still braving art's gatekeepers and the elements. His latest began true to form, on an icy river and with the barest of proposals—a sketch without text or a signature. He could look out from a Hudson River pier once stood (as seen in the photographs of Every Ocean Hughes) and a warehouse lay abandoned. Gordon Matta-Clark (who also created Hit and Run Gardens) took a blowtorch to it just when Hammons was applying himself to paper. It has become the subject of "Around Day's End" a look at the downtown scene back then. First, though, Hammons proposed the bare outline of a warehouse open to the elements, as his own Day's End, after Matta-Clark's original.

As always when it comes to an artist as impressive and deceptive, do not expect too little or too much. Where is his own mark or, for that matter, a sculptural object, and where can one stand to see it between water and sky? But then not even Matta-Clark could capture the city's landmarks or let in so much light. From the north, a square bay frames One World Trade Center even before one pulls out a cell phone to snap the picture. From across the street, its metal rods have a grace all their own, with a gently curving top rising to a new peak midway through. But then it is meant to be seen from passing cars or by cyclists, joggers, and New Yorkers out to enjoy the clouds and sun.

It is meant to belong to everyone, and legally it does. the Whitney paid the costs, but the city and state own the property, which is to say Hudson River Park, and Hammons did not receive a penny. It might never have come about were it not restoring or recreating what was there, while leaving the pier to one's imagination.  The law bars new construction along the Hudson. The artist's appreciation of the site makes a telling contrast with the ugly display of wealth nearby and at the Hudson Yards a mile away.

The law bars new construction along the Hudson. The artist's appreciation of the site makes a telling contrast with the ugly display of wealth nearby and at the Hudson Yards a mile away.

This Day's End came to completion on a damp April Thursday, although a crane still ran through it, with workers still perched at the far end. It had its formal opening for invited guests in May at, well, day's end, when Hammons, once again true to form, made no promises to speak or to attend—although Julie Mehretu, partway through her Whitney retrospective, did. Supporting steel and concrete cylinders could not yet blend into the river, although they promise to become more encrusted with life. The work should cement the museum's place here as well. A new Whitney by Renzo Piano opened in 2015 but feels familiar enough by now, as does tourist traffic along the High Line. Museum-goers have a fine view of Day's End looking down.

Like any riff or recreation, the work belongs ambivalently to past, present, and future. It pays tribute to an earlier time and a literal breakthrough, and Hammons, no longer new to New York, knew them well. He pays tribute to those days as well with his spare geometry, which Weinberg compares to the Minimalism of Sol LeWitt. Like painting then, he is drawing in space. You might prefer a Hudson with more amenities, like another winery or public restrooms. Still, art matters, too, and so does remembering.

Remembering can only look back. Crime is down, but so many opportunities for artists are gone. Hammons at seventy-eight is not getting any younger, and an avant-garde is not coming back. Who would have recognized in the old warehouse the elegance of its outline? But then Hammons was never all about tearing things down and letting things melt away. As an African American, he has too much to remember.

The best of times . .

The Meatpacking District lay all but abandoned, its piers rotting and empty apart from men seeking sex. An artist who ventured there received a warrant for his arrest. The twin towers were rising, not as an emblem of prosperity or a target for terrorism, but as a massive eyesore that few could love. The Bowery was still proverbially for bums. Did gentrifiers in Battery Park City scorn a powerful public sculpture? David Hammons pissed on it.

It was, in short, good times in downtown New York. Or maybe it was the best of times for art and the worst of times for a bankrupt city, but the Whitney wants to remember the good. A show of twenty-two artists sees them in collaboration, in challenge to the existing order, and at play. It commemorates Matta-Clark, who took his chain saw and blowtorch to the warehouse on pier 52 of the Hudson, as if to give the decade what it deserved. In reality, he was just letting in the light—pools of light amid the ruins, for Day's End in 1975. He got off without arrest.

A lot has changed since then and since the scene at Club 57, notably the arrival of the Whitney itself at the foot of the High Line. The museum is still bringing change at that. It commissioned Hammons, who never did meet Matta-Clark, to build his bare frame on that very site, on a pier that no longer exists. He calls it Day's End as well. With luck, it will overshadow Little Island, the park on an adjacent pier already in progress, with money from Barry Diller, the media mogul, and Diane von Furstenberg, his wife. Their vanity act rises on a cluster of white mushrooms—like upscale coffee funnels to keep the wealthy awake.

Hammons really did piss on Delta Sprint, a tilted arc by Richard Serra in 1985, as well as toss sneakers over the top. It was not, though, in the spirit of competition, and artists knew it. Serra, for one, had joined half a dozen others in solidarity, in the emerging shadow of the World Trade Center. They contributed photographs and postcards to preserve the view and to provide instructions for enjoying it—"in anticipation," one card reads, "of the equinox sunset." "Around Day's End: Downtown New York" opens in the Whitney's lobby gallery with a grainy film of the original Day's End, but Matta-Clark, too, had a head start. He had pulled off another incursion onto the piers on the Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The Whitney has at best selective memories of the years from 1970 to 1986. For all downtown on the margins, Soho was going gangbusters, and East Village art was just getting underway. If you stepped over a few druggies out on the street to get there, you may have felt halfway proud of your dedication to art or utterly ashamed. Christo must have felt the same ambivalence when he wrapped a hand truck as an ominous bundle. Martha Rosler announced her ambivalence with The Bowery in Two Inadequate Symbol Systems, photos broken by a dazzling number of synonyms for drunk. It plays off postmodern "theory" of the time, while refusing to be bound.

Not all is good news. By the show's end, gay men were dying of AIDS—the agonizing story told by Alvin Baltrop and, among the losses, Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz. Jean-Michel Basquiat speaks on paper of mass ghettos and work for "chump change," while Martin Wong paints, all too convincingly, a gated storefront. Still, the men in Hujar's photograph enjoy their felt necessity for masks, with paper boxes over their heads. Joan Jonas and her friends cannot stop playing around either, on film for Songdelay. As they revel in the mud, a hula hoop, and each other, they must wish that day never came to an end.

David Hammons ran at the Drawing Center through May 23, 2021, and his river project fully opened at sunset on May 17. "Around Days End" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through November 1, 2020. A related review looks at four shows by David Hammons.