Piety in Excess

John Haberin New York City

Painted in Mexico: The Late Baroque

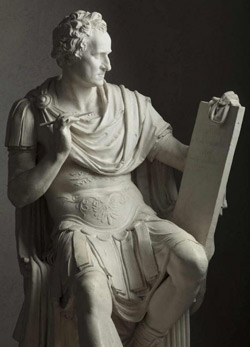

Antonio Canova's Washington

For a few months, the Met's European history extends deep into modernity and the Americas. "Painted in Mexico" unfolds in its wing dedicated to the twentieth century, concludes in 1790, and opens with the height of Baroque excess. Apotheosis of the Eucharist even sounds formidable. Angels and cherubs fly everywhere and nowhere in its towering oval, above the adoring Saint Francis and Saint Clare, and so does the brushwork.

Juan Rodríguez Juárez sets them all in the blond haze of soft flesh and a sunlit sky, with the gilded vessel of the sacrament at its very center. If that were not enough, a painting next to it shows the altarpiece where it long stood beginning in 1723,  the convent church of Corpus Christi in Mexico City. And then a third painting shows the church itself behind a spacious park, with an aqueduct bringing water to a growing city. Together, they situate Baroque painting in Mexico in a wider and wider world. Speaking of Europe in the New World, when North Carolina wanted a statue of George Washington in 1816, it turned to Italy. And when Antonio Canova looked for a model, he turned to antiquity—but first the wider world in Mexico.

the convent church of Corpus Christi in Mexico City. And then a third painting shows the church itself behind a spacious park, with an aqueduct bringing water to a growing city. Together, they situate Baroque painting in Mexico in a wider and wider world. Speaking of Europe in the New World, when North Carolina wanted a statue of George Washington in 1816, it turned to Italy. And when Antonio Canova looked for a model, he turned to antiquity—but first the wider world in Mexico.

Pride and prejudice

That world does not end with the borders of Mexico City. A viceroy commissioned the stiffer second and third paintings, attributed to Nicolás Enríquez, to convince King Philip V to support the convent in what, after all, was then New Spain. Franciscans attend to their business in the church interior, ignoring the altar, much like noblemen strolling about in the height of fashion. The Alameda Park modeled itself on the most stately of European gardens. And the New World returns the favor. The Met claims it for a fresh view of European art and its age.

You may have heard this story before. Just last year, an early Baroque painting by Cristóbal de Villalpando took two floors of the Lehman wing—a site more often associated with Post-Impressionism and the Robert Lehman collection. Others, speaking of the Met's twentieth-century wing and twenty-first century demands, have made the case for a global Modernism—including Bauhaus photography, Latin American architecture, Tarsila do Amaral, Lygia Clark, and Grupo Fuente in Brazil. Here, though, a museum banks on unfamiliar names and, to my mind, art's least inviting century. It also asks tough questions about what counts as proper European or American art. Just who were these guys?

The show is about pride but also prejudice. Painters boasted of their pure blood and Juárez of a dynasty. He, his brother Nicolás, and their cousin Antonio de Torres descended from painters. For the Met, they also set things off with a new style and new iconography, or religious signs and symbols. (Who outside the Vatican ever heard of an apotheosis of the Eucharist?) Yet their very excess corresponds to the decline of the Baroque on both continents.

Matters of prejudice also mark their subjects. The period introduced a new genre, costa, for paintings of mulattoes. Marriages between "barbarians" and whites produced more or less proper offspring, while those between indigenous Americans and blacks had to settle for the perverse miracle of albino children. Otherwise, local people and places appear only in religious processions, with colorful clothing. But then upper-class portraits and religious scenes dwell on surfaces as well, from brocaded dress to inlaid vessels. This is getting messy.

Surfaces and piety alike speak of excess. When Juan paints an Ascension, Jesus strides through the sky as if on his way to a street fight or a feast, while Jesus for Torres outdoes in musculature those who elevate his cross. At the death of a saint, for Francisco Antonio Vallejo, stars fall into the sea. From a sacrament to the Assumption of the Virgin, there is always room for another saint or another angel. Even as a child, Mary displays acts of piety that put mere humans to shame. At the same time, surfaces can always give way to a vision.

A revelation structures many a composition, just as a miracle takes up many a painting. That death of a saint has an actual opening in the sky and onto heaven. Portraits tend to stick close to the picture plane, as for Caravaggio at the dawn of the Baroque, often with a glimpse behind them and a leap into a far smaller scale. A revelation accords, too, with the frequent use of text, where the voice of the academy blends easily into the voice of a god. Some paintings incorporate books of instruction, both religious volumes and art manuals. Portraits often have a long inscription at their base, as a reminder of the subject's worth.

Old world and new

The show's very layout scrambles instruction in art with instruction in feeling. It has no use for chronology, which is fine: this style is going nowhere fast. Jumping around also allows names to recur, a huge help in dealing with a hundred works by artists difficult to remember. For all his excess, one can always count on Juan for a touch of skill and sanity. He brings dark eyes and spidery fingers to a self-portrait, and he alone gives a noble sitter a frankly worn countenance.

Instead, the show starts with the dynasty and the growth of "informal" academies, interrupted by religious narratives by "master storytellers." Then come still more genres—in costas and landscapes, noble portraits and nuns, and finally religious allegories and smaller paintings for private devotion. Almost all reflect the struggle to make sense of either piety or nobility. Many religious icons might have been carried in procession, blending new-world customs and old-world church rituals. (Francisco de Zurbarán may have intended paintings to be held aloft a century earlier, but they never did make it across the Atlantic from Spain.) Portraits may boast of wealth, aristocracy, or devotion.

Painting struggles, too, to embrace or to escape either world. The curators, led by LACMA's Ilona Katzew, represent institutions in the United States, Madrid, and Mexico City. They also translate the show's title as Pinxit Mexici, to stress that artists knew enough Latin to use it as a signature.  Juan's golden haze and soaring cherubs look back past Giambattista Tiepolo, a near contemporary, and Tiepolo's skies to Correggio in Renaissance Italy, and Enríquez closely follows Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci for a Baptism. Panoramas draw on Charles le Brun from the 1660s, while the preponderance of sweetness and light reflects Bartolomé Esteban Murillo in Baroque Spain. Painters worked on copper, as in Europe, for its chilly sheen.

Juan's golden haze and soaring cherubs look back past Giambattista Tiepolo, a near contemporary, and Tiepolo's skies to Correggio in Renaissance Italy, and Enríquez closely follows Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci for a Baptism. Panoramas draw on Charles le Brun from the 1660s, while the preponderance of sweetness and light reflects Bartolomé Esteban Murillo in Baroque Spain. Painters worked on copper, as in Europe, for its chilly sheen.

And then the native landscape intrudes, cautiously. The martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, perhaps by José de Ibarra, takes place in front of darkly glowing blues in the hills. Yet the section for "Paintings of the Land" has little in the way of land at all. Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz presents Mexico City as decidedly civilized vistas—with a plaza, a terrace, and a port. Even Ibarra's blue has as much to do with colorful surfaces as a view onto depth. But then independent landscapes were a novelty in North America then as well, and the Hudson River School was decades away.

Uniting them all is not their naturalism but the revelation. An overflow of devotion can mean softening the blow of the divine or the human. Ibarra's Sebastian bears the arrows of his martyrdom, but not their wounds. His Ecce Homo is so unmarred by torment that it appears to sweat blood. In allegories, statues in churches or processions seem to sweat as well, on their way to coming alive. Once again, the painting of piety has become the painting of a work of art.

The show has its embarrassments and then some, but also the pleasures of surface and vision. It also has the interest of what it leaves out. The weariness of Mexican peddlers, again by Ibarra, looks forward to a reality that art and culture still cannot confront. A clock and pocket watch as signs of wealth show how close they were to novelties, much as in medieval time at the Morgan Library. A folding screen tries to embrace both the courtly leisure of a French fête galante and native American customs, but it cannot be fully at home with either one. The old world of Baroque Europe is dying, and a new world in art is unable to be born.

Inventing America

When it comes to George Washington, either Italy or antiquity may sound unlikely, not even at the Frick. This is not the iconic profile or the man of action. The tricorne hat and powdered wig are gone, leaving just a few curls above a high forehead, prominent nose, and downcast eyes. Washington's sword is no longer at his side but at his feet, beside its sheath, and ancient armor covers his chest. A hand is raised from his side as well, holding a pen, while the other hand holds the tablet so that he may write. This is a different kind of hero, one capable of action, but also of restraint and thought. One might count him as a companion, a compatriot, or a model.

He may sound unlikely for another reason, too. Historians still debate what a historian, Gordon S. Wood, called the radicalism of the American Revolution. Did it build on representative government in England—and hold England to account? Or did it create something new, without an aristocracy and with a more active role for government in ensuring freedom, in what Gary Wills called inventing America? Either way, whatever is its first commander-in-chief doing in classical or modern Rome? Yet Thomas Jefferson himself chose Antonio Canova, who turned for a fitting likeness not to one of more than a hundred paintings by Gilbert Stuart, but to a sculpture by yet another Italian, Giuseppe Ceracchi, a quarter century before.

The president was seventy in 1792, but one would hardly know it from Canova's update. Why should one, for he had been dead sixteen years by 1816, and ideals had changed? America now demanded a place on a larger stage, with room for Italy. Art had changed, too, with the muss and fuss of the eighteenth century giving way to Neoclassicism. Jefferson, remember, adopted Roman architecture to his home in Monticello and the University of Virginia. Romanticism, too, was underway, although the statue will have none of it—and Canova, born in 1757, sat for his own brushy portrait, also at the Frick, with Thomas Lawrence.

Then, too, America was a source of changing ideals all along, and so was Washington. It was a nation of first colonizers and then immigrants, like Thomas Cole of the Hudson River School soon after, and a German, Emanuel Leutze, painted Washington Crossing the Delaware. Besides, Washington had set a precedent by stepping down, as general and then after two terms as president. And that is Canova's subject, for he shows his hero penning his farewell address, dedicating himself to the rule of law. The tablet so far shows only the Latin for law, homeland, and liberty—and Washington's armor likens him to Cincinnatus, the Roman general who stepped down rather than become dictator for life. Canova got so into these ideals that he had a history of the revolution read to him while he worked.

He did not have much to show for it, solemnity and silliness aside. A fire soon consumed the state capitol, which collapsed, crushing the statue to bits. North Carolina never quite arranged for its restoration, leaving a modest exhibition without its centerpiece. Yet Canova took pains. Loans from his birthplace in Possagno, near Venice, follow the process from two pencil sketches (one sharing a sheet with a study for an equestrian monument of another ruler) through four terra cotta and then plaster studies, or bozetti. He came up with a rough composition, extended its legs and dropped the toga, nailed down the pose with a nude(and no, please, this is not a daring or exploitative "naked George"), and then clothed it again and brought it to a finish. He was methodical enough, too, to have produced a full-scale final model, or modello, which has a room to itself in place of the real thing.

Washington took pains, too, in constructing an American ideal. Like Benjamin Franklin in Paris, who sat for portrait after portrait, he saw that as just one more part of his job. When he posed for Jean-Antoine Houdon, he lay on his back to endure a life mask. Sure enough, too, this was to be, at least for a time, a Neoclassical ideal in three dimensions. One can walk around the sculpture, to encounter it in profile and face on as well as in a quarter turn from the front. One finds a man both larger than life and resigning himself to the human.

"Painted in Mexico: 1700–1790" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 22, 2018, Antonio Canova's Washington at the Frick through September 23. Related reviews look at the Baroque in Mexico and Canova's late work.