The Modern Art Factory

John Haberin New York City

The Noguchi Garden Museum

In one of the quietest corners of the Noguchi Garden Museum, in one of the most reclusive corners of New York City, for just one slow summer, hangs a photograph of a woman. Caught from behind, her turbaned hair and bare body bathe in a soft light. She could be kneeling in the sunlit air that even now fills the former studio and workshop. Like the museum itself, she promises an experience that no New Yorker should miss.

No, I do not mean Man Ray's classic, doctored photo—those two f-curves outlined on a naked torso. His pun still surprises and challenges. Man Ray crosses the limits of the arts and of representation, not to mention propriety. This woman has just enough sex appeal to tease and capture the eye, just enough purity and calm to lull and appease it. She seems well at home beside the museum's polished and rippled stone.

In fact, I had not seen a work of art at all. I had seen an ad. It comes amid memorabilia, in a temporary exhibition of Japanese lanterns by Isamu Noguchi. Two other photographs show the floor displays at (ready?) Bloomingdales. If a trifle overcrowded and showily out of focus, they look gorgeous to this day. The display in real life looks even better.

From factory to museum

What does that say about the artist's fabled serenity as he dealt with reality—including the reality of the marketplace? What does it say about Modernism's fabled optimism? At least while asking, one might as well head out for one of the city's most neglected treats. By the very nature of utopias, one might well start to miss it. (A separate article looks at the Noghuchi Museum's renovation and 2009 reopening. Still another returns again on the museum's fortieth anniversary.)

It makes sense, really. While I shall incorporate insights learned from Man Ray, this story truly belongs to the Noguchi Garden Museum—further restored and renamed a few years after this 2001 review as simply the Isamu Noguchi Museum. Everything about the place speaks at once of the avant-garde's twin poles, gritty reality and a world to itself. Start with the museum's location.

It stands well apart, a long stroll down Broadway (or a short ride by bus) from Astoria's increasingly multiethnic community. A block away, I had the East River waterfront almost to myself. Even then, I had trouble finding my way as I left the struggling Socrates Sculpture Park only a block away. With art along the Brooklyn waterfront down for a year of park restoration in Dumbo, I felt lost. I looked right past the Noguchi Museum's factory façade, failing to spot the attractive entrance wall around the corner. Yet Noguchi chose the spot for a practical reason as well as the joys of solitude—for suppliers of stone nearby.

He must have liked Vernon Boulevard, too, for commerce of his own—his deliveries to clients. Now a tour bus uses the traffic-free streets to hit the borough's art attractions, starting with P.S. 1. Now, too, a ferry docks on Vernon Boulevard half a mile away.

Inside, one could phrase the dilemma as upstairs and downstairs. Think of it as servant's quarters versus a great man's independent means, only no one has hidden the hard work upstairs. No one would dream of trying.

One enters through sleek, late-modern architecture. Noguchi added its bareness, rich materials, asymmetries, and open spaces as he transformed the 1927 building into workspace—and then workspace into museum. An opening room holds a second, summer 2001 exhibition besides the lanterns. Two dozen works, on loan from Japan, show the artist at his most assured. They extend the course of other late work on display, both elsewhere on the ground floor and in the enclosed, airy garden outside.

From servant to artist

At the very end of his career, Isamu Noguchi worked on a large, roughly human scale. Like living animals, too, the sculpture sprawls oddly without losing stability. It rests on the ground without stands or supports—except where the base transforms the art object itself. Moving around a room's central partition made me think of wandering in a zoo as a child. Yet late work has become completely abstract. Dark materials suggest the monochromes of late-modern painting, in Noguchi's contemporaries from Mark Rothko through abstraction today. Arbitrary changes in texturing echo and subdue a painter's more extravagant gestures.

The layout upstairs becomes only slightly more prosaic, like a maze of numbered boxes. It could represent a deliberate shift backward, to the architecture of an earlier Modernism. Noguchi's career shifts with it. Its twin poles of art and urban reality do not.

One gets a brief tour of the sculptor's early career in Paris, under Constantin Brancusi. He learns effortlessly Brancusi's imagery and materials. One meets again those bronze skulls and slim, towering birds. Noguchi also has his fling with Surrealism, in tight arrangements of small objects. He then grows more abstract, but also more at home in the conscious, the familiar, and the prosaic. He is finding his way to a personal style, away from Modernism's dark interiority.

Elsewhere upstairs, the California-bred artist struggles in his role as public servant. He returns to Japan, where he also grew up, to commemorate victims of the atomic bomb. Later on, he worked alone and with Louis Kahn, the architect, on playgrounds along the Hudson River that would have made Sanford Robinson Gifford proud. Not one plan got built, in Japan or New York, but the artist never lost his utter self-confidence. For Manhattan, Noguchi submitted his projects again and again and again. A room devoted to the Japan project makes a fitting memorial quite by itself—only now, to an artist holding true to himself.

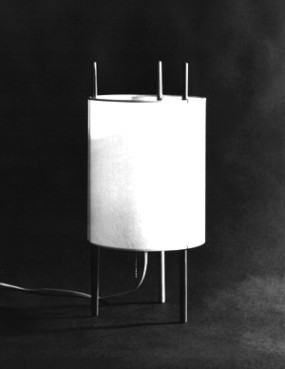

And then I remember those lanterns. I had faced work for reproduction and retail, blatantly decorative and functional, and I had fallen in love. One sees Noguchi paring Japanese tradition and its cheapened offshoots, building complexity anew. First the wooden rims go, and then the designs get trickier. The ample show takes care to show the construction. I could imagine myself taking a lamp out of its box, where it lies collapsed. I wanted to assemble it piece by piece for my own living room.

I liked especially some large boxes, bound only by freely hanging curtains. Peeking within the vertical, one discovers a surprise—not a bare bulb, but a second geometric structure. Imagine an enclosed ceiling lamp for the imagination's private chamber. In the play of light and form, along with its unapologetic marketing, I felt again the agony of late Modern art. I stood again between outside and inside, public and private, the institution and the imagination.

From utopia to earth

I thought of a play just on the edge of limits, too, as I walked again in the garden downstairs. I started by following the garden path, in its careful course past each work. Yet I could not resist breaking off to the small, loose stones for a closer look. I could not help running my hand through a slim sheet of water that trickles off the fountain.  If art here tumbles on the edge of nature, so did I.

If art here tumbles on the edge of nature, so did I.

The factory versus the museum, the special exhibition versus the career history, the market versus the product—each tells a similar story. Noguchi speaks to a modern artist's difficult identity as source for a richer art. As an American high modernist, with roots in three countries not long ago at war, he may well define the puzzle.

Noguchi settled in New York, heading more and more for abstraction, but he never fully outgrew the School of Paris. He kept that opposition of fragmentation and studied elegance. He relished both the escape into the unconscious and an ostentatious public persona. He looks back to early Modernism in its newfound purity, but also in its readiness to reshape every detail of modern life, right on down to furniture design. Yet he also looks ahead to Modernism's dissolution, in a newly burgeoning art marketplace. And it works—for modern art's long, remarkable moment.

Modernism has taken on the burden of utopia. Like utopias since at least Candide, it has had to face Voltaire's original charges—escapism and failure. For progressive critics of today's art world, that translates into self-involvement and selling out. It reminds conservative critics of their hated government arts funding, from Soviet projects once to sacrilege now.

Optimism and escapism, commercialism and failure, they could easily sum up, too, this artist without a country. Only Noguchi's history suggests some complications that this postmodern picture leaves out. Not everything succeeds in Queens, but so much does all the same, and modern art itself can, too. Think of the Modern and its collection, if only in brief, coming to MoMA QNS.

Noguchi's work may hang onto dreams of pure art, thoughts for the war dead, or care for children at play. His museum, in turn, often makes room for other artists in pursuit of legacy, like Gabriel Orozco. Each time, it accepts strong, positive moral commitments.

Modernism's ground zero

Perhaps most of all, Noguchi never rests on his pedestal. Like the avant-garde's self-questioning, his identity crisis keeps evolving. He gets rid of pedestals anyway or, like Gonzalo Fonseca, makes them one with the work.

He sticks close to the ground, shaping it with rises, arches, sunken areas, and enclosures. For his Ground Zero, he takes a memorial arch and bell from Japanese traditions. However, he also planned a tomblike underground for the names of the fallen. For New York, he may have picked up on the layering of levels, walks, highway, and riverbank already found in Riverside Park. The playful dips also remind the curators of Minimalism and earthworks, just then entering art.

The artist never got his way. The curators suspect that an American stood a poor chance in Japan, given who dropped the bomb. Certainly Noguchi raised unsettling issues of imperialism and guilt for a war's devastation. Then, too, the park plans could simply have died in a decade of urban neglect. They could hardly compete with Robert Moses's determination to level much of the city.

However, I suspect that he came off just a bit too arty for that public—and also not quite close enough to the comforts of a textbook. He stood further than I often remember from Surrealism's shattering of earth and sky. He stood further, too, than the curator's think from the fuss of later European sculpture, like that of Jorge Oteiza, from Minimalism's theater, or from mass-marketing. He really did want to sink into the earth. His calmness of spirit could not anticipate modern art's breakdown.

Escapism and failure, perhaps Modernism always needed them to succeed. No wonder the opposite mistakes, illustration and stardom, nurture Postmodernism now. In the anti-utopia of today—in the politics of New York's Ground Zero and a National September 11 Memorial, in its High Line and High Line extension, or in installations like those of Phoebe Washburn—one sees the same problem as in facing corporate empires, only intensified.

How long will the play of Modernism and Postmodernism last in the face of all that? For now, as in the garden, I can only cherish my memories and accept the risk.

The loan exhibition from Japan of late works and the display of lanterns ran at the Isamu Noguchi Museum through the summer of 2001, the exhibitions of collaboration through January 26, 2014. The museum reopened with a new hanging August 28, 2024, in anticipation of its fortieth anniversary. Socrates Sculpture Park remains open summers as well. Other related reviews revisit Isamu Noguchi and his museum for his encounters with Saburo Hasegawa and Christian Boltanski.