Beyond the Numbers

John Haberin New York City

Howardena Pindell and Sam Gilliam

As Rope/Fire/Water comes to an end, a long vertical crawl begins against an otherwise black screen. It might be the credits to an old-time movie, but for the words above: Black Lives Matter. Howardena Pindell has given names to the dead—more than a thousand, per a tally at the list's end. Her video, though, is not about the ongoing deaths from police violence, but rather a context in slave abuse and lynchings over more than a century.

It starts with another, more frightful tally for their cost in lives. As she says at The Shed, "the numbers say everything," except when they do not. There are also the names behind those numbers and their stories. There are also, too, images, and the show gives a further context in her collage abstractions and other works.  It is a long overdue challenge to put those pieces together. They go well together, too, with a black artist dedicated to color in two and three dimensions, Sam Gilliam

It is a long overdue challenge to put those pieces together. They go well together, too, with a black artist dedicated to color in two and three dimensions, Sam Gilliam

White paintings and black skin

Howardena Pindell has found two audiences over the years, and they may not even know that one another existed. Search for her online, and the first search suggestion will take you to Free, White and 21, her sole earlier video. It has entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, stood out in "An Incomplete History of Protest" at the Whitney, and has had people admiring and squirming no end since 1980. More often, though, she has appeared in shows of African American artists and at her gallery—in each case, for near monochrome abstractions on unstretched canvas. They gain their relief surfaces from cut photographs, museum matting, and more canvas, but chiefly from paper salvaged from hole punchers. Had Pindell been in charge of hanging chads in Florida for the 2000 presidential election, every ballot would have counted.

She made that first video at what must have felt to her a career peak. Born in 1943, she had nailed down a Yale MFA and a curatorial slot at MoMA—without precedent for a black woman. She had helped found A.I.R, a gallery by and for women that survives, last I looked, in Dumbo to this day. (She has since taught for many years at SUNY Stony Brook.) She had, though, survived a car crash the year before, in 1979. It must have got her thinking all the harder about who she was and who she and her country had been.

Free, White and 21 proceeds simply enough—disarmingly so. Facing the camera, she speaks of indignities received, starting but not ending as a child. When she pauses between stories, you can hear the sounds of a metronome ticking off every second and of traffic blissfully passing by, in case you missed them all along. Just in case, too, that you overlooked the sensation of a lecture, she endures one herself. Every so often a white woman interrupts to complain about the chip on Pindell's shoulder and about not turning her experience into art the proper way. Of course, the artist plays that part as well, in a blond wig, sunglasses, and tape for white skin.

Both parts feel heavy handed, but the stories and the hectoring alike ring true. Besides, if it is a lecture, Pindell is lecturing herself. She peels away the tape just short of painfully to reveal herself. For one last twist, she then appears with a bandage covering her black face, unwrapping it slowly but surely to reveal, well, I leave it to you to see. Certainties, she seems to say, are easy to come by but no less art and no less true. And then she went right back to her abstract art as, many a title called it, her autobiography.

Those titles have a point. She began her series while still at MoMA, where she scavenged materials. She stuck then to rectangular canvas in almost pure white, two tokens of the latest thing, as with Robert Ryman, but with a coarser surface. That surface, like the frayed edges of canvas, also bring home another imperative of their time, art as object. As she started over in the 1980s, she turned to rounder and more irregular shapes in still greater relief. Layers now include not just dots from a hole punch, but ovals and more. Pastels dominate.

The softness suggests the "abstract Impressionism" of Philip Guston before he gave it up for something more agonized and biting—with his Klan figures as an acknowledgment of racism. (If that has led to a show postponed as un-P.C., all the sadder for racial justice.) Still, Pindell's work is physical, personal, and even confessional. Blues derive from ocean life after a trip to the American Museum of Natural History. Later whites take pleasure in a snow day for kids in New York. Glitter brings one up close to appreciate its texture, only to see the sparkles vanish before one's eyes.

A display of lynching

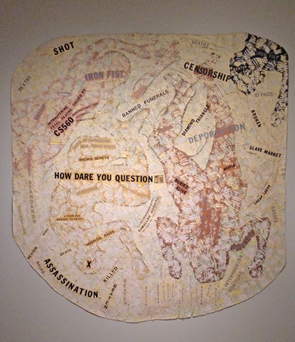

Can anything bridge her two audiences? She was dealing all along with her skin, in and out of white. Some reliefs bear the traces of her body, no doubt still on her mind after the car crash. The show, though, misses out on the chance to ask. The curator, Adeze Wilford, has way too few works for a retrospective like one that recently skipped New York. One might never know that some paintings riff on race more directly by incorporating text, like one at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Once again, The Shed seems out to live up to its name by leaving most of the floor wide vacant, with its next "Open Call" still to come.

Still, it has commissioned Rope/Fire/Water and two new assemblages, more pointed than the ones at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. One extends the video, as the story of Four Little Girls. The girls, killed in Birmingham, appear in a framed photo at the center of a heavy blackness. It bears the tally (those numbers again) of similar deaths in the civil-rights era. It also hangs above a comforting wealth of discomfortingly burnt toys on the floor. The second assemblage, of much the same size and blackness, recites the plunder of lives and resources by Belgium in the Congo—and by Columbus and his successors in the Caribbean.

The conjunctions may seem forced, despite their historical accuracy. As on video, they veer toward sentiment or another lecture, only to stop just short of either one. That back and forth may well account for their impact, and I can still feel the plushness and burnt edges. Two slightly older works look further to history. Their shapes allude to African DNA, she says, but surely also to the chains of slavery, and one actual chain hangs nearby. They also display photos of African totems and more text, enough to stand as due memorials.

The new video has its bridges, too. If her first video posed the personal side of racism, this represents its public side. Not only is it about American history, but every lynching was meant as a public display, to teach "those people" a lesson. They also served as entertainment, if hardly art, to the point that whites took bone fragments as souvenirs. If it comes so many years after her first video, Pindell proposed something like it earlier. Like Black Lives Matter, it has found its moment.

It is all about remembering, and she also speaks of the need to "cite facts" and to "give credit." It ends with brief credits after all, and each story cites its source as well—from Ida B. Wells and other activists to scholarly texts and new media. As if determined to stick to the facts, Pindell narrates the whole with hardly a trace of expression. She betrays surprise only briefly, when she recounts whites among the victims. (Naturally she has the numbers there to back her up.) The screen remains nearly an unbroken black for sixteen minutes, apart from the subtitles spelling out her voice and the metronome.

The stories are ghastly enough on their own, and you will not soon forget them. Some are famous, like those of Emmett Till and Medgar Evers, but many more are not, and the very anonymity of lost lives matters. I did not know of a children's march in 1963, where water from police hoses ripped off skin. As for the blank screen, images appear when they played a role in cruelty as a public message. Some circulated as postcards. I can only hold out hope to grasp better the place and quality of Pindell's images as a whole another day.

Color as mass

You can always count on paintings by Sam Gilliam to pop right off the wall. No, scratch that: what comes off the wall is color itself. He kept at it to the end at that, but with an unexpected closeness to the wall. Work in Chelsea from his last years thickens in the process, defying the lightness of his earlier unstretched canvas. Was he still first and foremost a colorist?

If you know Gilliam at all, you almost surely know him for curtains across the gallery. Born in 1933, he is forever linked to the Washington Color School (as in the nation's capital), along with Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis.  For Noland or Louis, stain is a matter of design, with clear symmetry and emblematic imagery in targets and veils. For Gilliam, it could be tie-dyed canvas left out to sing or to dry. As with Charles McGill, coming off the wall situates abstraction between painting and sculpture, but which comes first? But then why choose?

For Noland or Louis, stain is a matter of design, with clear symmetry and emblematic imagery in targets and veils. For Gilliam, it could be tie-dyed canvas left out to sing or to dry. As with Charles McGill, coming off the wall situates abstraction between painting and sculpture, but which comes first? But then why choose?

That generation did not. Critics in the 1960s loved to talk about "art as object" in the same breath with "flatness," for painters like Frank Stella. Gilliam might seem to prefer the first, when, after all, a painting literally bars the way. Yet it is color that, first and foremost, pops. He made clear the potential for Southern blacks and black abstraction, but he preferred to talk about color for its own sake. The very lack of design may have left him less visible than Noland, Louis, or (also at times in Washington) Alma Thomas, but there the physical object and its shape have their role as well. What happens, then, when Gilliam sticks to the wall?

For one thing, approaching his death in 2022, it returns him to the epic scale and rectangle of color-field painting. At the same time, the plot thickens. Paint itself does, heavily clotted to the point that color emerges both as image and highlight. Most of the paintings could almost be monochrome, give or take the interruptions. A mostly white painting would look just plain creepy without them, while a blue one would lose its depths of shadow in shades of blue. Store-bought glitter enters as well.

Canvas and its support thicken, too, with beveled edges. These are massive, labor intensive works, an unexpected turn for an older artist. Maybe Gilliam was consciously defying death. He may also have been looking for a greater simplicity after the stains. A smaller back room holds another late series—smaller, flatter, and still closer to the wall. There colors overlap and descend like lightening, as if to show that he, too, could paint. Out front, though, color comes down to the beveled rectangle.

Clotting and glitter can make anyone cringe. Signs of mass and effort in an older artist can make anyone wonder what he himself really did. They do, though, what big paintings are supposed to do: they take time and demand attention. Think of them as just another way to make color pop. It may take mass to produce color and color to produce mass.

Howardena Pindell ran at The Shed through April 11, 2021, Sam Gilliam at Pace through October 28, 2023.