Before and After

John Haberin New York City

Eugene Richards, Fred Herzog, and Helen Levitt

For most people, "before and after" is a cheesy come-on for a cheesier product. For Eugene Richards, it was a matter of life and death. He photographed his first wife before and after her mastectomy, with equal attention to first her pristine left breast and then a brutal scar.

Richards was never one to shy away from the unvarnished face of mortality, but not only that. He knew, too, to contrast the fear in her eyes on the eve of the operation and the relief in her face afterward, shining and raised to the sky. For him, terror means vulnerability, and vulnerability is a precondition for joy. Not that either has the final word, not when he also photographed what became her final treatment in 1979, raising one finger to her lips in anticipation of her silence. He did, though, take dying as a family matter—and not just for his family, at the International Center of Photography. Meanwhile in the galleries, Fred Herzog finds the blue side of photography in living color.

Street photography, you might say, calls for frankness. It is all about looking the obvious in the face, where others would just as soon turn away. Why, then, did Helen Levitt go in search of masks? A famous image captures three kids on a stoop heading off for Halloween. Well before Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus but without their more sordid view, she walked a fine line between spectacle, extremity, and the everyday, and so did her subjects. For both, life at its fullest meant no holds barred.

A matter of life and death

Eugene Richards follows families from cradle to grave, with perhaps a first communion or a nursing home between them. That could include his family, as with his wife's cancer or with his parents at once together and apart. His father sits at home, in a barely lit room, while his mother stands at an unbridgeable distance, her back framed by the light of a window. More often, though, it meant entering the lives of others. Richards saw them as caught up in larger events, like the fall of the Twin Towers or civil war in Beirut, and larger issues of poverty and race—but first and foremost as life histories. For him, too, the most fundamental fact of life is loss.

Loss means dealing in aftermaths rather than breaking news. He photographs gravediggers and funerals, from Arkansas sharecroppers to a man killed in Brooklyn for his coat. He photographs kids arrested for drug use, eyes wide, rather than junkies shooting up. He travels to Tiananmen Square, but only after photojournalists like Magnum Photos had captured the face of tanks. He photographs a silhouette at Ground Zero in 2001, like the ghost of someone already dead. And then he is back a year later with more dark ghosts on the Staten Island ferry.

Just who, though, is the loser? Maybe everyone, on stages in which the space between actors always threatens to keep them apart. Survivors may have an equal claim along with the dead—like a father contemplating his son's photograph or a doctor covering his face in his hands after the loss of a patient. Ironies abound. A sign in South Boston announces No Niggers Allowed, even as an African American cop shows up to protect the residents. Young blacks in the cocaine epidemic handle both real and toy guns.

Richards has the first solo show to cover both floors on the Bowery, with a hundred sixty works. The curators, Lisa Hostetler of the George Eastman Museum and April Watson of the Nelson-Atkins Museum with ICP's Susan Carlson, can easily juggle chronology and themes, since he so often worked in series—for books, for the Consumer's Union, and for Life magazine. He graduated in 1971 from Northeastern University, where, like Ralph Eugene Meatyard, he studied with Minor White, whose lessons are clear in the silhouettes or an early study in chiaroscuro. Like Robert Frank he crossed America. Like W. Eugene Smith, he saw himself as a witness to both individuals and their surroundings. Street photography here can mean a black kid in Massachusetts raising his arms in a dance or the poster for Wonder Bread behind him.

Richards sees people in context, caught up in more than they can control. A corpse in a Denver hospital lies behind bin after bin of medical clamps, and its death by gunshot cedes ground to so much more. Other assignments took the photographer to a prison farm, to psychiatric hospitals, among the "living poor" in South Dakota, and alongside Doctors Without Borders overseas. Still, a commitment to life stories makes their fate an everyday affair. It can be a joyful or grisly affair at that, if not both. A girl suffers a seizure in a backyard pool, but a return to Arkansas after more than thirty years finds Dorothy's red slippers from The Wizard of Oz.

An obsession with the personal veers often into sentiment, like that of an old man confronting his memories in a wedding picture. And an obsession with "issues" can carry obvious messages. Videos add the photographer's voice to slide shows of the still photographs, spelling things out all the more. A late turn to color undermines the balance of subjectivity and commitment through its appearance of objectivity, and the show's title, "The Run-On of Time," borders on meaningless. It is moving all the same. Real lives are on the line—and real deaths.

The pink door

All of a sudden, photography is taking color seriously. Exhibition after exhibition has celebrated its early champions, each with a reminder of why their choices matter. It helped Joel Meyerowitz capture the intensity of life on the street—and William Eggleston or Stephen Shore the lasting strangeness of America. It brought Raghubir Singh face to face with the shifting colors of India. It took Irving Penn and Jan Groover closer to classic still life or abstraction. Who, then, would dare have questioned it in the first place?

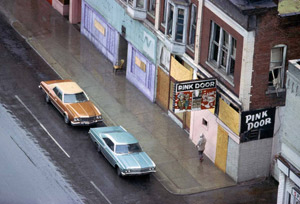

Was it all just snobbery and conservatism, the kind still defensive about art photography, like the AIPAD Photography Show, or still nostalgic for Eugène Atget in Paris? And where exactly were the shocks? Fred Herzog, for one, was always slightly off-color. He captures the dense neon glow of a red-light district. He parks his camera across from a boarded-up establishment in Kansas City named the Pink Door—with ugly brown and blue sedans parked, too, right outside. Their styling would look garish enough today in black and white.

Color for Herzog has something of the marginal and unseemly, much like colorful language. He might not have minded being marginal himself. Born in 1930 in Germany, he moved in 1953 to Vancouver.  Was Europe too frightening in the Cold War or too old world? Was New York too close to the center of the action or too remote from the life he knew? He also took up Kodachrome, relishing the cheapness of its hues.

Was Europe too frightening in the Cold War or too old world? Was New York too close to the center of the action or too remote from the life he knew? He also took up Kodachrome, relishing the cheapness of its hues.

It allowed him a shared medium with amateur photography, just as he shares the awkwardness of his subjects. This is not fashion photography or a freak show out of Ulrike Ottinger, but everyday life. The gallery calls twenty-five years of his work ending in the early 1980s "Modern Color," like a fashion magazine or photography manual from those same years, but do not be fooled. When he shoots a woman in a museum, one remembers not the art but her heavy shoes and the handbag clutched behind her back. One remembers even more the awkward red of her winter coat. Herzog might almost have painted it himself, on an otherwise near monochrome print.

Many of his subjects are looking, like the white woman looking at non-Western art or gamblers fixated on the numbers. As a couple crosses the street beneath (of course) a lavender umbrella, the man looks back. They are all in one way or other voyeurs, and they mark the photographer and viewer as voyeurs, too. Herzog can get away with it, because he is in no way above them, but can you? He is also more sophisticated than may appear. He cannot help noticing that the brown and blue cars almost match the wood and metal siding that has closed, at least from the outside, the Pink Door.

He does not change all that much over the years, but he does become less obvious. He still moves between day and night, from an empty barber shop to the casino, without a sunset in between, but the night has a strange beauty under artificial light. He thrives on the implausible multiplicity of urban signs. They could belong to Singh's overcrowded India, give or take their language. One might still dismiss his transient subjects in hope of something more lasting. Yet Atget himself preferred the "Zone," or shantytowns of Paris, and you are a guilty onlooker, too.

Masking the Depression

Helen Levitt loved the idea of street photography because she loved photography and New York City streets. She grew up in Bensonhurst, in Brooklyn, and spent much of her time in East Harlem and other poor neighborhoods of Manhattan. She admired Henri Cartier-Bresson and in due course got to watch him in action, but she would have traded her old used German camera for a Leica regardless for its portability. One can see something of his grace in a child twirling a ribbon like a hoop. She could not, though, have believed like him in "the decisive moment," not when her subjects would be back on the street again the very next day. She admired, too, Ben Shahn and the Workers Film and Photo League with their urban pursuit of social change, but she has far outlasted their moment of fame.

She found those three kids in 1939, in her mid-twenties, and this was Depression-era New York. While the girl in the back is just putting on her simple bandit's mask, children in many another shot rely on their own paper creations and the grit before their eyes. Two on quite another day treat the dirt on their faces as masks or war paint, while others make it hard to say whether they are fighting or playing. The kid with a ribbon could be wielding a weapon. Adults put in an appearance now and then, but with no effort to rein in the fight or the game. This is a child's world but without a trace of cuteness.

It is also in motion. Levitt took an interest in Walker Evans, too, and they spent a day together shooting on the subway. Her subjects, though, never stop what they are doing to confront the camera like sharecroppers for him or Dorothea Lange. They find their grimy dignity in action. The fight extends to the lintel over a tall doorway. If you are puzzled at how they got there, out a window or up a ladder meant for emergencies, another kid is ascending at left.

Motion is implicit, too, in the multiplication of images. Evans introduced her to James Agee, his collaborator on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, who later wrote the essay for her first book, A Way of Seeing in 1946. And he worked with her and Janice Loeb, the director and cinematographer, on a short film in 1952, In the Street. It looks like her stills connected as in a slide show or sprung to life. She also took his portrait as a thoughtful and attractive young man, and she visited Mexico City in 1941 with his wife and son. One can tell its poverty from New York's by the paucity of buildings, leaving space that swallows up its inhabitants in the middle distance.

This is and is not the city that a later generation would recognize, although Levitt turned to color as early as 1959. It has familiar enough housing, but no shops or street signs to help pin it down. It has graffiti, but in chalk. She later complained that her genre was getting harder, as kids stayed indoors and watched TV—and who knows what she would make of a time when letting them run free would count as child neglect? They are in poverty or at war, even screaming, but never in danger or in pain. They are looking after themselves.

The gallery calls this five decades of her work, perhaps to compete with a retrospective now in Vienna, and she continued making prints until sciatica took its toll well before her death in 2009. Still, most of the show covers just a year or two. She might look better still in narrower shows, each for just a series, but they would all walk that fine line between the imagination and the street. Graffiti becomes the site of a more literal street photography at that, in the sidewalk or the side of a building. One inscription claims a secret passageway, with a chalk button to enter. Press at your own risk.

Eugene Richards ran at the International Center of Photography through January 6, 2019. Fred Herzog ran at Laurence Miller through August 16, 2018, Helen Levitt through December 22.