Dreaming of Abstraction

John Haberin New York City

Searching the Sky for Rain

Paul Loughney, Richard Roth, and Julia Rommel

Deep within a basement tunnel lie some troubled sleepers. For SculptureCenter, they are dreaming about and questioning abstraction. They are also "Searching the Sky for Rain."

If the connections here look suspect, some days it seems that everyone is questioning abstraction. It comes only naturally with the revival of painting. Paul Loughney does it by literally blackening Cubism and Richard Roth by not so literally packing it in boxes.  How else to place painting in both two and three dimensions? Julia Rommel does so, too, when she finds that she can no longer paint according to plan. And she likes it that way. My fall tour of abstract painting leaves me wondering how a critic can judge.

How else to place painting in both two and three dimensions? Julia Rommel does so, too, when she finds that she can no longer paint according to plan. And she likes it that way. My fall tour of abstract painting leaves me wondering how a critic can judge.

Waking slow

A basement is an awkward place to be searching the sky, but the show is all about waking into knowledge and into art. Five recumbent figures by Eric Wesley have their own pedestals, widely spaced and running the length of the tunnel. They are New Realistic Figures, and all are philosophers, from Plato and Confucius to Postmodernism. In an alcove upstairs, a slowly unfolding slide show hones in a single restless face. You must trust Shahryar Nashat that he will wake to a catalog of Cy Twombly. Small ceramics by ektor garcia suggest a living nightmare.

It could be a long awakening—and only for the privileged few. If you do not recognize Jean, Gilles, and Michel as philosophers from their first names alone in Wesley's titles, you do not deserve to know. If you do not know Edward Said, in a portrait by Charles Gaines, for his merciless critique of "orientalism," you are part of the problem. If you are the sort who treats Twombly's abstraction as a sleeping aid or a talisman, you may be worse. As wall text explains, the sole question is this: "who has the right to abstraction?"

That may sound strange, given the realistic figures and a paucity of abstract art. Carmen Agote bases avocado and iron patterns on a water filtration system in LA, and Johanna Unzueta has a drawing high on a wall, but whatever are they doing in an institution called SculptureCenter anyway? Polished red by Jala Wahid enlarges a cow's liver, for those who take abstract art as a clue to the beauty or ugliness of nature. Wesley mounts large circles of stained glass on metal poles, but that is about it. Riet Wijnen's diagram of canons and exclusions in abstraction could take a page from William Powhida. Like the show, he positions his questioning within a broader sense of rights—of who has the right to speak at all.

For me, the pursuit of diversity is never enough, because it is only just beginning. For the Center, it also ignores "the ways in which the art industry regulates, classifies, compartmentalizes, and essentializes difference" in the first place. Like criticism of Dana Schutz at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, as a white woman speaking against racism, it is about who owns diversity. Mandy El-Sayegh takes the question personally, papering the walls with newsprint while borrowing from the family attic. Tony Cokes outlines the civil rights movement before, you know, white liberals made its leaders into icons, in text slides backed by a pop song. Rindon Johnson's long titles for his limp rawhide run to lectures themselves.

One has to defer way too often to the artists as authority figures—a shame in a show questioning authority. It is a shame, too, in that insider knowledge can get in the way of some playful art. Wesley's circles on poles represent, or so he would like you to believe, not magnifying glasses but burritos. Gaines also sets his numbered squares on Plexiglas in front of a photo of Central Park both to deconstruct and to amplify its beauty. When Tishan Hsu lays green ceramic tiles on a cement landscape, he brings indoor plumbing to the desert. Michael Queenland tosses about latex balloons and trash bags, as if to say that the party is already over, but at least it had first to begin.

As Theodore Roethke put it, "I wake to sleep and take my waking slow." Others are listening to SculptureCenter itself. Rafael Domenech lets its walls bulge inward like a vulnerable human body. Becket MWN plays on the basement infrastructure, while a plastic shed by Jacqueling Kiyomi Gordon serves as an "acoustic tent" for "canceled frequencies of the building," but is that enough? Is it even true? No, no one has the right to abstraction, because art is not a right but very possibly a greater good—and no one has the right to stop it.

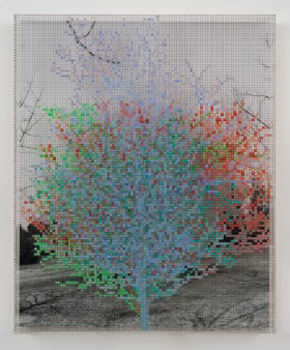

Cubism after dark

For all its visual acuity and its mind games, Cubism had little time for black. Not Paul Loughney, who updates it for the millennium and carries it into the night. One can recognize his spiraling, colliding sepia tones from Analytic Cubism or early Francis Picabia. One may not recognize the equally fragmented black fields in which they move.  Small works bring them together in collaged paper. A more impressive assemblage obliges small ones to find their way across adjacent black walls, rooting them all the more firmly in time and space.

Small works bring them together in collaged paper. A more impressive assemblage obliges small ones to find their way across adjacent black walls, rooting them all the more firmly in time and space.

One cannot recognize in the least their source. Loughney leaves in bits of newsprint on white like flashes of artificial light, but never enough to make out their message. Their stock looks stiff and reflective, and he depends for their quality on fashion or other upscale magazines. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque meet Andy Warhol, only to skitter off into abstraction. A show called "Confetti of the Mind" sounds like eye candy for lazy eyes, and Loughney has no problem with a playful sophistication. He places his work within the contexts of Modernism and pop culture while putting off its meaning for as long as he can.

One can see why Picasso and Braque worked in daylight—although I would not be so sure about Juan Gris, much less Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. They worked before the electric grid reached a majority of homes and artist garrets, and they worked in the still-life tradition. They pictured breakfast tables with the morning newspaper, not glossy advertising, because they were disassembling time while bringing news. Forget all that. Part of the condition for the revival of painting after Postmodernism is that there is not much news about art left to bring. It has necessarily become eclectic and hyperactive, translating formal constraints into repetition and excess.

Distinctions between genres are breaking down, too, even in the interest of abstraction. In a summer show, Rose Kallal set translucent materials in plinths lit from within, as "Polyphase Transition Tesseracts." They carry interior design and architecture into virtual assistants and mobile devices. She also sets the same parallels and color fields in motion on a large screen. It is easy enough to animate dull abstraction with digital video, and many do. Here, though, painting, craft, and new media unfold together in real space and time.

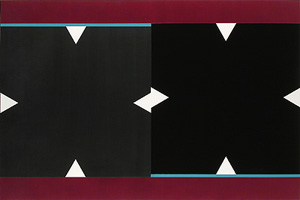

Richard Roth has his boxes, too, but decidedly low tech. He describes the work as acrylic on panel, but the panel has deep sides, on a scale ranging from a cookie box to an easel painting. They carry a pattern into depth, as a continuation or a counterpoint. A trapezoid descending into black meets its match in a slimmer trapezoid against white. Circles, adding up to a rectangle bulging in all directions, take on color. The thick border around a blue rectangle becomes further rectangles—and the edges of the box.

Roth's fields of black and color have a contemporary parallel in Don Voisine and Gary Petersen. They, too, are back, making their already complex compositions cleaner and livelier by messing them up. Roth also recalls the glory days of shaped canvas and "art as object," but he is literally painting outside the box. He does not so much build a composition on the shape of the frame as paint across it. He names the show after Spuyten Duyvil, or "spouting devil"—the turbulent waters separating Manhattan Island from the Bronx. He must like how the edge of the mainland has shifted, as mere humans filled the natural passage and dredged a canal.

Riffing on abstraction

Artist statements often run to boasting—about the media they have mastered and the big ideas they have in mind. Julia Rommel sounds more as if she is confessing to how little she understands. "Each painting," she writes, "quickly strayed from its initial plan," and then it took her ever so much longer than she expected to undo her mistakes and to follow where it was going. Still, her pride is showing. With her fourth show at a Lower East Side gallery, Rommel might have every reason to think that she has her style down by now. And plainly the appeal of painting for her is that she does not.

She runs to large rectangles of quiet but light-drenched colors, sometimes overlapping or set askew. Thinner bands serve as frames or punctuations, often with brushwork running looser along them, but also thinner and drier to the point of grain or stippling. The use of the rectangle to anchor a composition while resembling a window onto the light recalls Richard Diebenkorn, and so does her color scheme. Up close, one can see her slowing things down that much more with cuts and creases. One can see the stippling as self-reference as well, representing the artist's hand like the broad brush for David Reed. In the process, familiar elements become hers.

Should I be surprised, then, to run into much the same elements just days later in Chelsea? Shane Walsh shares a contrasting geometry and brushwork, although each canvas has a predominant color. In place of folds, he has collaged canvas as a slight intrusion into the third dimension, like iron-on patches. As with Rommel, the big gestures and colors throw one back, while the intrusions draw one close. The gallery compares his compositions to those of Frank Stella and the brushstrokes to those of Roy Lichtenstein, but I am not so sure. Still, the grain and curves have something of the etched steel in Stella's transition from painting to relief sculpture.

The gallery may have another reason to invoke Lichtenstein. It sees in Walsh everything from Pop Art to video games. Again I am not so sure, given the unbroken abstraction. But then any show, like Rommel's, called "Candy Jail" might not mind the comparisons either. Anything goes these days, from realism to abstraction, now that painting is back but formal demands are gone. Anything goes, too, in recycling signatures from artists past.

That is why some critics deplore "zombie formalism," and I am not convinced by that either. Still, the thought captures a real dilemma. If anything goes, where is it going, and what counts any longer as "derivative art"? Take another reference to Stella, in bands of color derived from the painting's edge in Rachel Hellmann. She uses shaped wood rather than shaped canvas, fanning well out of the picture plane as with Elizabeth Murray. And then, for a further surprise, the fanning becomes the mere illusion of a third dimension in watercolors.

Neither the freedom nor the recycling sounds all that auspicious, but it may help to see them together. Each artist here is riffing on much the same chord progression to a different end. Amy Sillman likes those chords, too. Maybe it is just my bias in favor of abstract painting, but I can take pleasure in that. It makes judging difficult, and I feel guilty picking anyone out for praise or blame. But then maybe critics should take their playbook from Rommel's proud and humble confession.

"Searching the Sky for Rain" ran at SculptureCenter through December 16, 2019, Paul Loughney at Lesley Heller through October 20, Rose Kallal at Lyles & King through August 3, Richard Roth at Margaret Thatcher Projects through November 2, Don Voisine at McKenzie through June 9 and Gary Petersen through October 20, Julia Rommel at Bureau through May 5, Shane Walsh at Asya Geisberg through May 10, and Rachel Hellmann at Elizabeth Houston through March 22.