Dripping with Irony

John Haberin New York City

Ed Ruscha and Course of Empire

A New Yorker knows irony. Detachment, not so much.

We have irony in the very air we breathe, with or without haze from Canadian wildfires. We value a quick mind, even as we know that everything we know is wrong. We know the city's pace and passion, too, and Ed Ruscha opened to members at the Museum of Modern Art right after Labor Day, the same day as the Armory Show. He has the entire top floor, and yet no artist speaks so deeply of and to LA.  When he paints maple syrup or screen-prints chocolate onto all four walls, he is dripping with irony. As for detachment, you bet.

When he paints maple syrup or screen-prints chocolate onto all four walls, he is dripping with irony. As for detachment, you bet.

I have climbed the Pepsi sign in Long Island City, because a New Yorker takes nothing for granted as just part of the neighborhood. Ruscha paints both sides of the Hollywood sign, front and back, as if each were equally iconic, and perhaps it is. He photographs Every Building on the Sunset Strip, for an artist's book. Where a New Yorker would look around to cherish small differences and to remember the haunts that fate has left behind, he loves their collective anonymity, or does he? A retrospective teases out what drew him to California and what he fears for today. It asks where he enters the work and when he vanishes.

What could sound lamer than art in the public interest, especially when the public fails to show up? What could sound more dated, too, like a leftover WPA project still struggling for completion? And yet, as a postscript, his Course of Empire multiplies the ways in which art can respond to pressing needs. It also looks backward to more than one moment in time, for a portrait in miniature of the American economy and American art. I get a smile at older work by Ruscha, such as "Honey, I weaved through more damn traffic today," but how much more? Judging by Course of Empire and his drawings at the Whitney, he can hold more that I ever guessed.

Pop goes text painting

That first accordion book, from 1966, folds out impressively, to almost twenty-five feet. The Strip runs just a mile and a half, but the act of photographing was impressive, too. Ruscha shot from a flat-bed truck. Was he erasing differences or asking one to discover them for oneself? He is not saying, but he returned to the medium to photograph LA apartment complexes and their architecture. He also paints a popular restaurant, on La Cienega south of Sunset Boulevard, as if it were on fire.

He paints LACMA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, also up in flames. Is he mocking its status, fearing its demise, or celebrating a city on fire? He could be deriding its pretension, soon after its construction in 1965, but not its art, right? Was he himself still making art? Hostile critics were asking that about an entire generation, and he was among its instigators. He seems to place everything in quotes, and the quotes are not just his alone.

Ruscha liked to position himself within a solidly American culture. Opening wall text starts right in with a quote, with the offhand grammar of a man of the people. "I don't have any Seine River like Monet," meaning of course Claude Monet at the origins of Impressionism. "I've just got US 66 between Oklahoma and Los Angeles." He does not mention that he first made the drive in 1956, at age eighteen, to study at CalArts (then Chouinard Art Institute), like many an up-and-coming artist. That year Around the World in 80 Days won the Oscar for best picture, and he was going places.

He does not mention, too, that he made it after all to Europe, in 1961, and photographed what he saw. He photographed obsessively in LA as well, often as the basis for painting. His second book sticks to gas stations as far away as Texas. Not that any one photo stands out as art, but then why should anything stand out? Not that he is hiding anything either. He is always open and never on view.

He had his breakthrough with text paintings, like John Baldessari, who later taught at CalArts, but without the reflection on art itself. Instead he runs to such simple messages as BOSS and OOF. Is he bossing you around or crying out against the oppressor? Already he is hard to pin down. It has left him always famous and never quite beloved. I still do not quite know what to make of him.

Those messages sound like sound effects in comic books, and other text paintings feature Annie, the little orphan. Yet he has not a single dot or scene from a comic strip, unlike Roy Lichtenstein. Annie takes its font from the original, as does a can of Spam, actual size. These are brand names, but Spam will never be as bland or halfway inviting as Campbell's soup for Andy Warhol. He paints gas stations but not the larger than life cars of James Rosenquist, like advertisements. Is it even Pop Art?

The fires of myth

Still, this is Hollywood, and so is 20th Century Fox. Ruscha paints it in 1963 as The Big Picture, and it is another breakthrough—clean, clear, bright, and big as its name. He shows the film studio's logo with projection beams behind it, crossing one another against a dark sky. The text in text painting has grown and entered three dimensions. Its overall shape tapers off behind the logo, facing front at left. Hollywood is myth-making, and so is he, while claiming the myth for himself.

He likes the "horizontal thrust," as he called it, so much that he applies it to gas stations from his photographs, with spotlights behind them as well. He must have loved how a station sign reads Standard, another myth. He goes on to indulge in luxury, with residential swimming pools. Nothing else matches that early half decade of work, but almost immediately he draws back. He must have distrusted the myth. He sets it on fire and watches it melt.

The curators, Christophe Cherix with Ana Torok and Kiko Aebi, present his career in sequence, but every step brings a change in theme. Ruscha does not give up a single motif. He just revisits it askance and afresh. Norm's restaurant, LACMA, and the very sky are on fire, a word that enters text painting as well. A C-clamp tugs at the text of another painting, while other text takes on the illusion of muck and goo. He backs off painting entirely for a few years, with such media as tobacco stain, blood (his own), whisky, and gunpowder.

The curators, Christophe Cherix with Ana Torok and Kiko Aebi, present his career in sequence, but every step brings a change in theme. Ruscha does not give up a single motif. He just revisits it askance and afresh. Norm's restaurant, LACMA, and the very sky are on fire, a word that enters text painting as well. A C-clamp tugs at the text of another painting, while other text takes on the illusion of muck and goo. He backs off painting entirely for a few years, with such media as tobacco stain, blood (his own), whisky, and gunpowder.

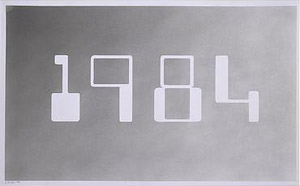

Was this his personal descent into darkness? When he returns to pastel and oil paint, the text is more skeptical—including skepticism about Artists Who Do Books. And then it darkens as well, into outright blackness. Paintings, now larger than ever, have such premonitions of death as the edge of clock face, set eternally to Five Past Eleven. Blocks of black seem to have censored others. This cannot end well.

Ruscha revisits thrust paintings in time to display at the Venice Biennale in 2005. A series of five alludes to Course of Empire by Thomas Cole, and I return to it in more detail below. Here Hollywood's empire has given way to bleak industrial buildings—including the dead end of a trade school, a logo in Chinese, and a tool and die company, with the accent on die. The full retrospective ends a year into the Trump presidency, with the American flag still flying but in tatters. The artist, too, is running out of steam, with few works in the new century. The flag risks a bland realism.

I prefer the deadpan optimism that brought him halfway across the country from Oklahoma City to the Sunset Strip. (He took the same highway to revisit family now and then.) It infiltrates even his chocolate room from 1970. Its wall covering, printed on paper, does not so much as stink. A New Yorker's hopes may lie elsewhere, and so may many a history of postwar art. Still, most of all in the 1960s, he keeps you guessing as he carries Pop into conceptual art.

But of course!

In his drawings, Ed Ruscha turns into an illusionist unlike anything in his early canvases or artist's books. Letters leap into three dimensions, against a background of light and shadow executed with consummate precision. One sees the same patience with the medium as he shows for subject matter in his encyclopedia photographs—also at the Whitney—of Southern California emptiness. The gray may look like pencil, but Ruscha somehow draws with gunpowder, much as another LA artist, Jack Goldstein, reads in advance of a page on fire. It makes Ruscha's painting of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on fire sound dangerous.

With his five paintings after Thomas Cole, Ruscha certainly means to engage the present, too, including the personal and the political. Each invokes one of those prefabricated buildings that line American roads. One industrial building lies deserted, like the Southern California of drawings by Ken Price, behind a decrepit but still menacing wire fence. Another has vanished entirely, leaving little more than a bare tree and threatening skies. Others have suffered "repurposing"—as a chain store or as a new acquisition for the Asian economy. The Chinese characters on a building's face can only add to the disturbing anonymity, even if one has not seen Chen Chieh-Jen's videos of factories in Asia.

Still, unlike the more philosophical abstractions of Lawrence Weiner, a past collaborator, Ruscha keeps looking back. The paintings return to the sites of his 1992 Blue Collar series, when each building played its role in a vanishing lower-middle-class suburban economy. Now you know what happened next. They return to the days of Ruscha's large-scale narrative work, such as the 1968 Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, and the block lettering for building logos keeps up his habit of painting words. In the attention to sky, storm clouds, a fiery sunset, and equally eerie morning light, they remind me as well of the pencil and gunpowder shading in his works on paper, which finally convinced me that I was seeing a real artist. They look back, too, to a time in the twentieth century when political art meant art about the working class.

Of course, they also revisit the 1830s with the Hudson River School, which took his beloved landscape from the state of nature to culture and back, thanks to periods of flourishing, decadence, and violent destruction. Even apart from its subject matter and history, Ruscha's Course of Empire reflects America's global dilemma (what Isa Genzken calls its Vampire/Empire) and art's possibilities for entering the public sphere. Ruscha geared up quickly to fill a gap, as the country's late entry into the Venice Biennale. As usual, the Bush administration has trouble remembering it actually belongs to the international community. Critics have noted that the trademark blankness of Ruscha's lighting actually looks back more to Canaletto's Venice than to Cole's Hudson River.

The Whitney stepped in the next year, in 2006, to fulfill art's public role in its own way, by giving the surprisingly unheralded show a domestic stop. (Have I said often enough how the museum has been taking American art seriously recently?) It temporarily reduced the display of its permanent collection, adapted one of its larger floors since Oscar Bluemner already occupied the second floor, and displayed both Ruscha series on long, freestanding facing walls, angled ever so slightly toward one another. I wish it could have borrowed the original Course of Empire, too. The New-York Historical Society has lent the work in the past—most recently to Philadelphia, for a survey of Hudson River School. Here the photographic reproductions in light boxes look deceptively small and out of reach for Cole's American sublime.

Ironically, while Cole invented American painting's meditation on civilization and the wilderness, he could hardly have imagined America as something of an international empire. Even the Mexican war lay ten years away. Ironically, too, the decaying sites of Blue Collar come closest to Cole's final scene, in which nature starts to reclaim an empty land for itself. Ruscha's latest subject, with the destruction of blue-collar hopes, looks more like Cole's penultimate stage. Maybe one day Ruscha will wend his way back another stage, only to find a teeming despair.

Ed Ruscha ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 12, 2024, "Course of Empire" at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 29, 2006. Ruscha's drawings and photographs ran at the Whitney through September 26, 2005, with a related display of a collaboration with Lawrence Weiner on a book of photographs at P.S. 1 through September 27 as part of a group show, "Hard Light."