Fraud and Theft

John Haberin New York City

Peter Carey's Theft: A Love Story

Who the $#%& Is Jackson Pollock?

The idea of an art world as a unified field and an unstoppable force persists. It enters more than a few sensible critiques of art institutions, including late Modernism's white cubes, global politics, haute bourgeoisie markets, and museums that cannot quite promise an alternative to all these. Call it the last postmodern myth, and at least one novelist calls it his own as well.

Peter Carey has lived in New York for some time, long enough to have an American son—and, now, a tale about how New Yorkers can really ruin a reputation. Naturally the author of My Life as a Fake can hardly write about fraud in the art world without wondering whether the art world is itself a fraud—as if art by its nature did not already traffic in fictions. Theft: A Love Story indeed turns on authenticity, both of art and of its artist hero. Its very title reminds one that even a critic of fakery has to learn to deal in illusion.

Meanwhile, an alleged masterpiece turns up in a thrift shop, and a film about it, Who the $#%& Is Jackson Pollock?, calls their power a fraud. Carey's jaded artist shares the profanity and would surely agree. Just who, however, is perpetuating the fraud?

No truck with art?

Is "the whole art world a fraud," then? One can always count on that theme to sell a few books or magazines. It appeals to a public unease with art since Modernism, even while people pack the modern museum. It appeals to a phony right-wing populism that still plays politically, directed perversely at artists, scholars, and others on the outside of real wealth and power. It appeals to qualms about soaring prices, even as auctions add to a work's aura and the public's reverence. No wonder it appeals, too, to The New York Times.

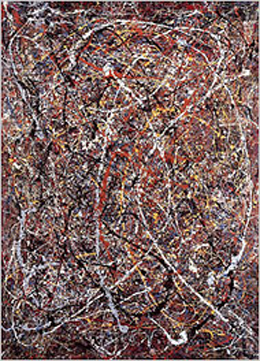

Twice in a week, the paper reports on a painting that may or may not pass for the work of a great American artist. Teri Horton, whom I quoted in the preceding paragraph, bought it for five bucks at a thrift shop, and she has been trying to validate it ever since. Her story pits an outspoken woman against art historians, who dismiss it as worthless. It also makes her the star of a new movie, Who the $#%& Is Jackson Pollock? The film neatly aligns her contest with another, between "the connoisseurs, who insist that a refined eye is the ultimate judge of authenticity," and "the scientific side." Thomas Hoving, former director of the Met, stands in for the former, while the forensic evidence comes from fingerprints.

The film leaves no doubts where its sympathies lie, and The Times clearly shares them. I can see a case for them, too, despite myself. Sure, the paint looks too flat, dense, close in its weave to the canvas edge, matte, and simply boring for Jackson Pollock—at least in a newspaper thumbnail. An unsigned drip painting does not yield its secrets easily, however, and fingerprints sound convincing. According to a Canadian investigator, they match those on a Jackson Pollock in Berlin and others from Pollock's Long Island studio. Still, while I cannot judge a reproduction, and while one may doubt the whole idea of authenticity after Modernism, I can evaluate journalism, and here alarms should be sounding loud and clear.

As in politics, one should be questioning the populism alone. Hoving made his reputation, as New York parks commissioner and at the Met, by opening Central Park and the museum to a larger public. Meanwhile, The Times would not be covering this twice in about a week unless a bigger business than the art world were promoting a movie. Not surprisingly, then, the film's scenario sounds like a market-tested formula. Both a "feisty" woman and a former truck driver with an eighth-grade education—one who hated the "ugly" mess at first and could not give it away? One can hear audiences cheering already.

Horton may look for hidden motives, but no one else's Pollock drops in price if this one sells. Conversely, the movie depends on buying into the worth of a Pollock, so that this one can gain in stature. Moreover, by denigrating visual examination, the film effectively detaches that worth from anything like meaning. One also wonders who hired the investigator, how he obtained the prints, and whether any museum labs got a look. Real science is open and replicable, and art forgers often start with canvas from the right time and place.

Finally, just who neatly aligned those two conflicts—between insiders and outsiders, connoisseurs and science? Attribution always relies on scientific examination, because inspection, knowledge, and understanding go together: they are about developing an informed eye and a receptive mind. Hoving's museum would test the pigments against Pollock's. It would use microscopes, radiography, and other tools to compare the density and weave of paint. And when careful examination does pay off, in what I see and know, it may not have film audiences cheering.

WTF?

So who the $#%& is Jackson Pollock? I often thought that this site would have even more readers if it covered the culture scene and all the arts. Then I might really rate as top critic and insider. A possible solution? Cover movies I have not seen. Oddly enough, in this article I have done just that, and to my dismay it has turned out rather well.

To sum up the plot again now that I have seen the movie, a California trucker bought an ugly painting for a few bucks. Teri Horton meant it as a gift, which already says something about her truculent personality. Who the $#%& Is Jackson Pollock? celebrates that spirit, as a healthy antidote to a conspiratorial art world. Hearing who may have painted the thing, she responds with the film's title. From that moment on, however, she will not give it up until she considers herself and, secondarily, the painting "vindicated."

My having leapt in myself before the movie's release, based solely on two articles in The Times, seems only right. After all, the film is all about judging without looking. In fact, it comes down hardest on those who bother to look. Its chief villain, Hoving, sticks his nose in the purported Pollock, backs off, turns his head at every possible angle, and otherwise subjects himself to ridicule from quick and dishonest jump cuts. The Met's former director even wears a slim, well-tailored suit. In this film, that alone puts him under suspicion.

The story alone sets off alarms. Who painted what truly does matter—and not just to art's inner circle. Rather, understanding art takes words, and one has every right to take into account such minor details as what the work looks like to someone who knows Pollock's style. In the movie, those mean old experts keep asking, too, about the work's history, or provenance: how could a painting by the most celebrated artist of his time leave the Lee Krasner estate, vanish for fifty years, cross the country, and land in a thrift store? Are other pieces by famous artists just laying around pawn shops in NYC right now?

Horton did not suddenly cause the producer, Don Hewitt of Sixty Minutes, to see the light. His program has sneered at those who dare admire such artists as Jean-Michel Basquiat as far back as 1993. And he still looks on hard questions about art as akin to passwords for a secret society. That may explain why the movie speaks with a former museum director rather than a Pollock scholar. The director, Harry Moses, works in television, with such sterling credits as The Guiding Light. And it shows—right down to the feel-good and thoroughly annoying ending, when Horton and her friends enjoy some good old country guitar

But then I probably said all this much better before I finally caught the DVD, which again says something about a shallow, conventional film. It takes on faith the credentials of the fingerprint expert she hired. It never asks other labs to confirm his efforts. It never pursues questions about the reliability of fingerprint evidence—including the clarity of the print or the frequency of a pattern within the population. I hope I do not go to jail on grounds like these.

Love and learn

Peter Cary's novel shares the belief in a secret society. His title cuts more than one way at that: just who or what is worth loving, and what is worth stealing? The painter at the center of Theft: A Love Story leaves no doubt where he stands.

To judge a work, you don't read a fucking catalogue. You look as if your life depended on it.

Just who, however, is stopping "you" from looking? Is it the power of critics, dealers, and museum curators? And is looking enough without their help anyway? In this fraud investigation, keeping track of police, criminals, and innocent bystanders takes real work. The quote, in short, runs headlong into what critics, dealers, and their buyers do.

Do galleries exist to sell art, and do commercial pressures distort art and its public? Sure, and that spells trouble. Chelsea's shopping mall and endless art fairs even apart from the Armory Show do discourage looking, and that encourages work extroverted enough to grab attention. It leaves in doubt art's ambitions to change the world politically, which depend on its place as "symbolic speech," between ordinary speech and an ordinary commodity. It encourages a culture of insiders, critics as curators, and gossip. It puts in question the continuity between art and the avant-garde.

Do catalogs, too, exist to sell art? They do for galleries, where they generate less independent revenue than for museums. They often twist scholarship and critical theory into not just artspeak, but what I call martspeak. However, dealers and their catalog writers also benefit from a working relationship with artists as museums rarely can. I rely on press releases myself all the time.

Museums, too, have money and careers at stake, and they, too, can bury art in words. They have a legal and financial obligation as nonprofits to educate the public. Yet the Met often uses wall labels to skew a work's importance and attribution.

Does the only hope, then, lie in sincere, cranky Booker-prize winners, who are just looking? No way, for dealers in Chelsea's "battle for Babylon" fight hard for work in which they believe. In turn, artist collectives and other attempts to take galleries beyond the fringe have motives, too. Worse, those fringes can create an insider culture, much as with private clubs. Most important of all, no amount of sincerity ensures understanding: it takes more than time, determination, and an expletive to look at art.

Back to bitterness

Art does take words—to inform new habits of looking and to upset crusty, sincere old ones. Art can also upset a trust in unspoiled, authentic beauty. A controversial attribution takes knowledge, experience, ideas, scientific examination, and gut feelings, but the interplay of all these matters whenever art makes one think, feel, and look. In an unnervingly naive chapter title of an unnervingly market-driven book, an economist named David Galenson asks, "Can an artist change?" He has his doubts, up, because his young geniuses do not back down, while late bloomers come upon complexity full blown. Not only artists, however, but viewers do change, as talent and understanding meet experience.

Each skeptic here has a huge stake in the market. That includes TimeOut, Sixty Minutes, a woman with a painting she hopes is worth tens of millions, and a well-reviewed novelist. Each is sincere, too. So why should they doubt that those who stake their lives on art are human beings, too, with the same mixed motives. And why should it make them doubt the value of thinking hard about art? Take one last look at each story.

The film pretends that art attributions ignore scientific methods. Yet it shrugs off chemical analysis that finds acrylic paints in the alleged Pollock. Acrylics did exist, but until reformulation in the 1960s only as runny, expensive stuff Pollock could not have used and might never have seen. He had good reason anyway for preferring the layered translucency of oil, the glow and cheapness of enamel, and their associations with art traditions and household materials. Even Horton's demand for vindication makes no sense, since it implies that someone who never heard of the painter and hated the painting had all the answers from the start.

Carey sets his tale in the Reagan era, which today's inflated prices and egos have left far behind. And his subtitle, A Love Story, suggests that art may have a happier handing than his hero. Australians have a culture wracked by change themselves. A traditional elite, certified by art schools and university entrance examinations, faces pressure from home for diversity—and pressure from abroad to accept a half century of European and American art. No wonder Robert Hughes plays the embattled elitist, even as he writes for popular publications, shuns critical theory, and dumps on emerging art that once served as the mark of an intellectual elite.

Still, one should never confuse a film's or a novel's genuine insights with its characters' grudges and hard knocks, and Carey's look back to the Reagan era has a point. A reactionary decade led to Chelsea just a few years later. Then, too, a president who despised New York had a good lesson for understanding it: as he said of the former Soviet Union, trust but verify. If you allow yourself to trust and to verify, you may come to love art. If you accept neither what you see or what you read, you may end up a bitter, failed artist in a novel.

The idea that contemporary art is all a hoax for insiders dies hard, even as audiences for artists like Pollock and Basquiat soar. The survey haunts me most for pointing to a changing scene, in which the arts sit beside top chefs and new fiction, rather than dive bars and semiotics. If I am looking for a secret society to help me make real money, though, I am banking on the Hewitt group.

Peter Carey's Theft: A Love Story was published in 2006 by Knopf. Those two articles appeared in The New York Times on November 15, 2006, but an earlier article on the proposed Pollock had appeared one week previously, and an article based on an interview with the fingerprint expert appeared December 31.