No Second Thoughts

John Haberin New York City

Frank Walter, Della Wells, and Yvonne Wells

Everything for Frank Walter was a throwaway—and everything a discovery of who and where he was. At his death in 2009, the black artist left thousands of paintings and drawings on top of hundreds of hours of tapes.

That is just for starters. His two thousand photographs run mostly to Polaroids, because what could come more quickly, with no chance for second thoughts? A stack of paper, a single manuscript, reaches easily to one's waist. Who would dare to turn its pages even if one could touch? Who would dare, too, to call it a memoir, a fiction, or a lecture on art? And still he sought, as the show's title puts it, "To Capture a Soul."

To be sure, there is hardly a soul in sight at the Drawing Center. An African woman in pencil may not count as a portrait, no more than a young Fidel Castro nearby on the wall. They are emblems of something more lasting than a lifetime, much like his carved wood after African sculpture. If they are also suspiciously generic, he could live with that. Like all of nature, they respond to him. Does that make him an outsider artist—and what about the sophisticated African American art of Della Wells and (no relation) Yvonne Wells?

Climbing the family tree

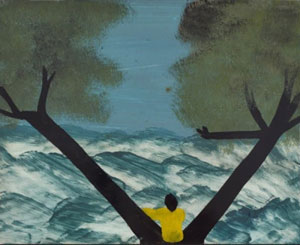

For so undisciplined an artist, Frank Walter stuck to a task long after another would have moved on. He could well have been high-functioning autistic in his embrace of ritual, his refusal to hide anything, and his absence of confession. If there is a self-portrait anywhere in his work, apart from the body of work itself, it lies in an otherwise anonymous man up a tree. Yet he left his native Antigua in 1953, still in his twenties, to find the other half of his heritage, and he remained in Europe until 1961. Another artist might have spent those years in museums, to claim their tradition as his own, or immersed himself in white, African, and Caribbean communities for their humanity and culture. Walter headed for the library.

Or rather he headed for libraries, that marvel of English cities, because he could do nothing singly. And there he turned out one family tree after another. Naturally they are dense to the point of illegible, their words covering entire sheets. Who can say what sprang from library research, what from a remembered oral history, and what from an active imagination? They have a curious echo in drawings of actual trees, their leaves a splatter of red and black akin to an explosion. This artist's god does and does not lie in the details.

Back home, he pursued the same uncanny mix of the obvious and unexpected. Maybe you know Antigua for sunlight and white sand. Walter sees rippling water in a dark wood, even as it emerges into the light. The sun rests on a mountain peak, like the product of a volcano. Animals are sketchier (and awfully cute), but they tend to one another when they are not looking at him. A cow jumps over a fence, if not the moon.

If they border on nursery rhymes, Walter wrote music, too, in typically sloppy but mostly accurate notation. Anything can go into the mix, and anything can as a ground for oil—including photocopies, disks of auto insulation, backs of unsold Polaroids, and boxes of film. The curator, Claire Gilman, arranges things roughly by subject, because she has no choice. Work from nearly sixty years is almost entirely undated. It may not be consistently great either, but he never have cared for greatness. He wanted only to see himself as part of a larger world.

If Walter leaves things a bit sketchy, Josh Smith embraces the charge. "This is how it is," he writes—and it has to be, because it finds completion in what is yet to come. "It refers forward," he claims of his work, but for once it also looks back, and he conceives his show in the Center's back room as an homage to Walter, as "Life Drawing." Is this real life? Since his debut in the 2009 New Museum "Generational," Smith has become an art-world favorite for what another group show called "everyday abstraction." Here, though, he tends to leaves, fish, birds, and palms as well.

If Walter makes art his fever dream and culture his library, Smith has appeared in a show of "The Feverish Library" as well, and he still piles it on. I have dismissed him more than once as slapdash, glib, and cheesy. There is no doubting, though, his facility and charm. Even the Grim Reaper looks anything but grim. Can he make Walters self-conscious childishness look downright grown-up? Maybe, he seems to say, there are limits to adulthood.

Sunshine on a cloudy day

For Della Wells, it is always a sunny day. Butterflies are free, and sunflowers rise with the sun. Sunlight suffuses her exuberant collage, to the point of a bright yellow sky. Even clouds and shadows are blue. Girls and women wear their Sunday best, indoors and out.  It will never rain on their parade.

It will never rain on their parade.

They got sunshine on a cloudy day, every day, so why are their faces sulking, angry, determined, or scared? Wells knows their feelings well, and she is on their side all the same. This Is Our House, a title declares, and she is out to make it hers—and to share it with others as African Americans. Her latest work, dense and colorful, is a wild ride. It can be hard to believe how well it coheres into something so recognizable, familiar, and comforting. Beverly, Don't Let Your Fears Paint Your Picture, another runs, and Wells never will, but the fears will not go away.

Nor will the stereotypes in the face of history. Watermelons can turn up anywhere, high up on flagpoles or resting casually on a shelf. So can chickens, gazing up at Beverly herself, peeping out from a tote bag, or behind a brush. Both dare to compete with the American flag. In another artist, like Kara Walker, stereotypes would signal satire or shame. For Wells, they are just business as usual, funny, and fun.

Not that her actors will ever settle for stereotypes. That shelf holds books along with a slice of watermelon, looking downright scholarly. This is the black community, and it demands to be taken seriously. It is also changing before one's eyes. The front of one building pasted onto another becomes a church. Wait a Minute, another title warns, but do not wait too long.

Think again, it warns, and collage here demands rethinking. It can be hard to know indoors from out—or magazine clippings from drawing and paint. One portrait is Simply Paul, but nothing is quite so simple, and Paula has a red circle over one eye like a bruise or a lens, Beverly a black one. Another clipping turns standard-issue packaging into a yard sign: Fragile / Handle with Care. You had better take care, too, before assigning this art your own stereotypes and expectations.

Wells, a self-taught artist at a gallery dedicated to just that, has the obsessive imaginings of outsider art and the subject matter of folk art to boot. Still, she is way too self-aware for the labels, and her collage looks back to Romare Bearden and others as well. Above all, it will not sit still—not if that would allow white eyes to define it. The show is "Mambo Land," but another yard sign promises antiques. To Paula's right, a girl rises past the borders of the picture, literally and metaphorically, leaving only her skirt and feet. Now in her seventies, Wells, too, is rising, but with her feet on the ground.

Half-crazy quilts

Yvonne Wells could have been a classic modern painter and a class act. Well, maybe just once, but a work from 1994 would be eye-catching even if it were not hanging right there over her gallery's front desk. Four rows of red squares run nearly nine feet across, set against black. Simplify, simplify, simplify, it says, not minimally but boldly. So what if each row broadens to include a mish-mash of colors and zebra patterns, and the black has a slim white border. These are her African American Squares.

Wells has a flair for stitching chaos together just long enough to keep it under control. An earlier work has an uncharacteristic lightness, with touches of color running here and there through a still lighter field. Never mind that it may yet unravel, for this is Untied Knots. Still, the two works introduce what may seem at first a welcome change for the gallery as well. It specializes in dense renderings of black and Caribbean culture, in fabric and paint, by such artists as Willie Birch, Shuvinai Ashoona, Myrlande Constant, and Dawn Williams Boyd. Eye-opening as they were, was it getting to be too much of the same?

Wells marks a turn to clarity and abstraction, or does she? She, too, uses "assorted fabrics." as the gallery terms her medium. Tapestry and hangings serve as painting everywhere these days, so fine. Keep looking, though, and her patterns make a point of quilting, starting with the show's earliest work, Round Quilt from 1987. She makes explicit her debt to African American craft with her latest as well, The Gee's Bend Way. Her designs may run out of control even by that standard, too. She does, after all, have Crazy Quilt.

She weaves not just abstraction, but a way of life. That mad design includes a bare branch, a pumpkin smile, and a cross. A striped quilt holds, she says, a sprit face. Wells calls another fabric an apron. A woman's work is never done, especially an artist's. You can judge whether she is sincere about either one.

That sounds duly pious in the manner of much of art's diversity. Maybe so, but another work has half a dozen Crown Royal labels—enough to get everyone drunk, whoever they be. The logo disturbs the regularity of jigsaw shapes in white while anchoring them in black. Once again, Wells is crazy but focused. Unnamed creatures enter here and there as well. When she calls one That's Me, maybe it is.

The show does not run in anything like chronological order, but then Wells does not change all that much over time. While the choices become increasingly representational, she sticks to her guns. Still, she can seem to take the easy way out. Her abstraction does not sit still long enough to create a signature image, and representation does not settle firmly into a culture or a myth. Still, she bridges boundaries between both worlds, with a degree of skepticism about both. She also has those reds.

Frank Walter and Josh Smith ran at the Drawing Center through September 15, 2024, Della Wells at Andrew Edlin through August 9, and Yvonne Wells at Fort Gansevoort through November 2.