Black Blocks and Red Stripes

John Haberin New York City

Censorship, Jenny Holzer, and Three Flags

Why should one accord the distinction between text and image so much weight? Both express something—or many things. Both may enter through the eye. Both may go into a work of art. Consider two apparently simple examples, of all too familiar signs and symbols, but of little more than black bars and red stripes.

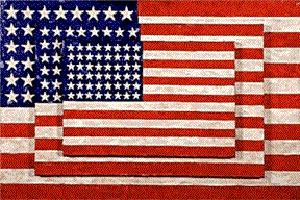

Perhaps more than anyone, Jenny Holzer has restricted contemporary art to text. Long before, Jasper Johns put stenciled words and familiar images on equal footing. Yet Holzer has turned to canvas while obliterating most of the words. And with Three Flags, Johns left out the words entirely.

Plain language

Each artist bends over backward to respect traditions of the pure, painted image, but with very different strategies. Stranger still, each now ends up mired in conflicts over politically charged signs and symbols.

As well they should. Holzer's redaction paintings appeared in 2006. Torture is, for a time, the declared policy of the United States, thanks to a travesty of democracy—an agreement between members of one party, reached in the office of the vice president, rather than open debate in the senate chambers. (Another artist, Jill Magid, in fact dramatizes the "Bybee memo" that justified all this.)

It is no longer the work of a few bad apples, nor a false rumor planted by left liberals about dark chambers that never existed. It is no longer the very pretext for an otherwise unprovoked invasion, bringing democratic values to a nation ruled by an evil tyrant. It is no longer the last resort for a lone, courageous agent faced with a ticking bomb. Those are last year's excuses, before the half-remembered nightmares of medieval witch trials and Stalin's gulag became standard operating procedure, wrapped neatly in that American flag.

Long before all that, Johns took on one of the most familiar signs in any language, written or visual, and now a proposed flag-burning amendment risks reducing it to a partisan message. And now Jenny Holzer has adopted the medium most associated with fine art, painting, but in order to display declassified documents, including those detailing the most painful abuses of war, back before America admitted and embraced them. Maybe art can never quite abandon words, at least without shutting me up. And that suggests a further connection between text in art and obliteration, the politics of censorship.

What, then, is at stake when art adopts words—or effaces them? Is art itself text? A related review looks at Jenny Holzer at the start of a new administration. A 2009 retrospective covers fifteen years of her work. Here I set aside the long view for a question as urgent as her crawl screens.

To introduce art and text, I have chosen two artists known for plain language—the language of LEDs, inscriptions, and stencils. I could have chosen other incandescent text, by Monica Bonvicini, not to mention block letters from Lawrence Weiner or antiwar scrawls by Raymond Pettibon. Either way, words themselves create the art object. They seem, too, to speak for themselves. Yet I have also chosen works that efface words or eliminate them entirely. Confused? You are already off to a good start.

Effacing the difference

Jenny Holzer's canvases should shake anyone up concerned about art and censorship, only starting with people who assume that she despises painting. Holzer's crawl screens rely on industrial materials and a transient, commercial medium. Her occasional monumentality, with the same elliptical texts carved in marble, treats art and hypocrisy with equal disdain. Besides, the sculpture, too, picks up Minimalism's anti-esthetic, much as the crawl screens animate and disperse tubes of fluorescent light from Dan Flavin. How, then, can she make painting so appealing?

Without question, her latest acts of protest look strangely elegant and go for wildly high prices. Yet even in painting she is adopting a technique that, with Warhol, once meant its death, and she gives his silkscreen a black mark, many times over. Her black streaks replicate the mark of censorship, but they stand as well like raw flesh for Leon Golub for other absences—lives that have paid the cost of lies, torture, and war. With the blur of Gerhard Richter, Richter's late work, and Richter's photorealism or the smear of an Andy Warhol silkscreen or Warhold Rorschach test, any visual indicator appears, as Derrida might put it, under erasure. That suggests how, in the hand of an artist, the marks of a censor may paradoxically release meanings.

Holzer's show included one crawl screen, and the medium has me straining much as ever to make out a message that I might have begged to avoid. Her paintings, in contrast, make a great deal of text easy to read. The government alone, they seem to say, bears responsibility for any omissions, and viewers who will not attend to every word abet the crime. One document recalls a previous era of us versus them, singling out the painter Alice Neel and her "consort" as obvious communists. A declassified memo after the first Gulf War shows Colin Powell's three-page response to criticism of defense policy—reduced to letterhead, a paragraph of polite evasion, blocks of magic marker, and an official signature.

However, the bulk of the show keeps up with the headlines, and any trace of humor vanishes. Like Edmund Clark, Holzer records abuse of power in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantánamo Bay. As yet another irony, here the censors omit nothing of the horror but the names of detainees, reducing every single instance to a relentless, handwritten alphanumeric code. The anonymity compounds the brutal maltreatment, suggesting that both aspects of the machine of war crush a human identity. Up close, the weight of evidence is crushing, too, and so is its avoidance by the press and television. From a distance, the black marks and the worn surfaces characteristic of silkscreen becomes more haunting, as if stepping away these makes lives disappear yet again.

While some canvases stick to black type on white backgrounds, others adopt garish color, and still others appear sober and burnt. The documents also multiply voices and points of view—as art will. They range from official investigations and records of interrogation to the first-person accounts of both soldiers and civilians. Yet if everything justifies presenting this as art, should you wonder how Holzer can put so much effort into addressing a self-selected audience of gallery-goers and collectors? Rather than preaching to an atonal choir, why not gather the indictment as a book, like the articles of impeachment that currently sit among new paperbacks in chain stores? I think not, but any qualms should vanish right across the street, where photographs document Holzer's projections on public buildings.

Few will recognize the sources, from Walt Whitman and Wislawa Szymborska to the vernacular. They blur the distinction between lyricism and politics, the personal and the political—with their intersection that much more the domain of art. Photography lends the texts a physical dimension, too, as if tearing at the words. Gazing at the central New York Public Library or Rockefeller Center last fall, one could take the façade for granted and deal easily with the projected words. In a gallery, the bending of light around pilasters becomes inescapable, adding further layers of distance and, yet again, a perplexing beauty. And yet my qualms remind me that art's place in the political arena always remains an open challenge.

Capture the flag

Who could imagine the Fourth without the flag everywhere in sight? And the Whitney has ushered in the holiday with a classic sighting. In its museum-wide celebration of American art, a Jasper Johns flag painting welcomes visitors to the third floor. It looks so bright that one can safely forget he later rendered the flag in gray.

But suppose a constitutional amendment, banning desecration of the flag. Would those images still have a home? Now, no one at the Whitney is complaining or apologizing. Three Flags even flies high on the museum's home page and in advertising for the exhibition. "Full House" also leads to a lesser-known and less-colorful flag, Mapplethorpe's photo of an icon nearing the end of its days. Have I, then, asked a stupid question? Do not be so sure.

For one thing, do not underestimate the artists. Of course, Mapplethorpe has gotten museums in trouble before, and his image dates three years after President Nixon's resignation and two years after the fall of Saigon, perhaps the last time that the flag occupied such contested ground. However, for Johns, too, art's loyalty to American values seemed anything but certain. Abstract Expressionism had everyone talking about whether American culture had triumphed, and the state department even took an interest in its public-relations value.  One can see Johns as turning against the New York School in all its triumphs. He painted his first flag in 1955, only a year after Senator McCarthy's censure, with memories still fresh of cultural figures grilled on Congress— and he would not consent to a public display for three full years.

One can see Johns as turning against the New York School in all its triumphs. He painted his first flag in 1955, only a year after Senator McCarthy's censure, with memories still fresh of cultural figures grilled on Congress— and he would not consent to a public display for three full years.

Perhaps Johns meant no disrespect when he made a flag look so stiff and made it far too "in one's face," literally so, to salute. Perhaps he did not anticipate a Democratic "surrender monkey" when he painted his White Flag. Still, do not underestimate politicians out for an easy moral victory either. The 2006 Biennial took no flak for distributing free posters of torture at Abu Ghraib, by Richard Serra and so apparently far from his sculpture and drawing, but the press and politicians leapt all over Amy Wilson for that same image not long before. "Full House" is taking no flak either, but what if the Whitney sought funding for exhibiting closer to Ground Zero near the National September 11 Memorial? What if Mayor Giuliani were again the next mayor—or president?

Also do not underestimate the passions of ordinary citizens or the complexity of the issues they would face. You would have to decide, say, whether to keep displaying a flag as worn and weary as Mapplethorpe's or, conversely, to trash it. Others, perhaps the government, would get to ask what you mean by that decision, especially as no one can remember an actual flag burning for the law to target. Such ambiguity endangers the arts far more, too. For every work of art that seeks to send a clear message, many more refuse to do just that, by their very nature as art. My preceding history notwithstanding, politics may hardly have entered Johns's mind.

Protests against America merit defense, because they may call for policy in America's best interests—or because the right to protest is itself in the interest of democracy. Protests that try to seize the higher ground of American interest, where both sides stand for the constitution and a nation's standard of justice, occur far more often, and they, too, deserve protection. However, one should not overlook either how often art gets in trouble because it refuses to give answers one way or another about what it or America means, and people prefer easy answers. I myself cannot say for sure in which category to place controversial images on display this past year, including a flag draped across a gallery by Hans Haacke before his emptier show at the X-Initiative, a flag straitjacket by Lisa Charde, or a flag that James Lee Byars may once have soiled with his shoes on his way to a typically come-what-may event in Southern California. That ambiguity is keeping museum lawyers busy right now, but it also has a lot to do with why your own thoughts and actions need protection. You may not think of Jasper Johns when you hear about a flag-burning amendment, but maybe you should.

Is an image text?

Is an image then text, and if not, why do people keep wanting to censor it? Surely image and text belong together, as what another show has called "Drawing Time, Reading Time." One goes too far in leaving documentation to a museum gift shop or in divesting a library of art. Yet what strikes me most is how readily many artists and critics have abandoned the distinction. Call it the legacy of Cubist collage—or of a Modernism that, after Postmodernism, refuses to go away. Call it the triumph of Dada, structuralism, the Internet, or call it just the press release and price list by the gallery door.

Everyone understands text and images alike as ways both of communicating with others and of expressing oneself. Everyone interprets paintings with words— except, perhaps, when the act of interpretation produces another work of art. Whether one is just learning about art or looking for fuller understandings, mute astonishment just will not do the trick. No wonder that postmodern critics, especially those influenced by Jacques Derrida, often use "reading" when they mean interpreting, understanding, or even just looking at art. They have ceased to think of art and text as a shared space, to the point of speaking of art as text.

Conversely, some critics talk about the entirety of reality as reduced these days to mere images. I include both conservative fury at declining values and still other post-structuralists—those influenced by Jean Baudrillard. However, suppose I could set heavy politics and heavy theory aside. Even then, books, magazines, and TV alike get one absorbing words and images together. One-of-a-kind artist books conjoin text and image still further.

Why, then, might the distinction between art and text still matter? Why might a different artist than Holzer, Simryn Gill, have excised text entirely by hand rather than blackened it? Why would I wish to swim against such strong critical and cultural currents? How could a reactionary critic over in England, John Carey, ever hope to regain the distinction to prove the superiority of literature to the visual arts?

I might start with the brain: people may have the ability to perceive images "hard wired" into the mind. People understand mirror images as themselves, but most monkeys do not. The brain may make perspective's illusion as natural as looking through a window, even if history teaches how much else goes into such a convention.

Images may or may not come hard-wired into the brains, but they definitely do not come hard-wired in exactly the same way that text does. For one thing, images do not need to refer to anything, although they accrue associations right and left, whereas words belong to a language, which supposes meaning. Images can vary freely, becoming new images. Letters, in contrast, are so discrete that one perceives the same word when the serifs on its letters grow longer or vanish entirely. Grammatically, linguistics since Noam Chomsky argues that every language has a structure, which we learn only because we are born that way. Semantically, Structuralists say, words mean by contrast with other words, whereas images carry meaning in a far more fluid context.

Art as text as metaphor

Artists often feel that culture gives too little weight to the distinction. They so hate when critics and the public reduce their work to its supposed meaning and message. They often remind me how little I understand what they do. As Laurie Anderson famously said, "writing about art is like dancing about architecture." Ironically, even the artist's book gains in resonance when one can hold it in one's hands, like a bibliophile betrayed by an age of digital and disposable text. A "downtown" type like Anderson expresses much the same nostalgia for that immediate, personal experience as an "uptown" collector of rare books.

Yet here, too, I have gone too far. Art reaches its viewers through what they know, which means through their insights and their words. And a healthy postmodern distrust of the media's power over perception and conduct embodies a healthy political skepticism as well as the air of a bad science-fiction movie. I suggest seeing art as text as a powerful metaphor, but still a metaphor—and so itself both art and text. Art as text amounts to more text, which allows it to spin out new meanings, including insights into its own limits. One often thinks of iconography, the symbols in a Renaissance painting, as a visual language akin to accounting or hieroglyphics—and yet it contributes to a felt realism and functions in a context of representation.

If art, then, refuses to separate itself from text or to become text, what happens when one encounters text as part of art? One encounters it in ever-changing ways, as when Jennifer Bartlett pretends to codify the vocabulary of abstract painting. A viewer today expects that encounter, starting at least with Cubism, and the collaboration between poets and artists helped give birth to Dada. In other words, in other words.

Does inclusion of text within art, then, efface the distinction, by joining the two, or cement it, by giving text the weight of a found object—or perhaps the risk of infection from a foreign body? It may depend on how one examines the text. It may depend, too, on what kind of frame one puts between the work and the world. With Robert Rauschenberg, the Met argues in its exhibition of his "Combines," letters often function as shapes, but not always and never exclusively.

Text in art, then, must literally take shape, and its language no more aspires to having the final say than any other image. It points to past dialogues bereft of their conclusions and to past meanings now bereft of their words. Not surprisingly, quotations going back to Cubism often come from newsprint, where past events took shape in a newspaper's signature, decorative, block type. It also often overwrites other images or other words, as in the boldly tangled histories of David Diao and Mickey Smith.

If these strategies seem to resemble those of a political censor, that suggests another feature often common to text art, anger. Going back at least to Berlin Dada, art came as the bearer of bad news. When art makes headlines and artists read newspapers, it is not solely because the artist comes into confrontation with the public, but also because the work reveals angry divisions within its publics. Art as text and reality as mere image are both revealing, but only because both supply metaphors for angry divisions within experience—and so does art. No wonder people so often wish to suppress it.

Jenny Holzer's paintings and crawl screen ran at Cheim & Read and her photographs at Yvon Lambert, both through June 17, 2006. They help one to talk about political art. Accompanying reviews look at a Jenny Holzer retrospective and Holzer at the Guggenheim. A related article looks at artists who combine abstraction, color charts, and text.