When Global Art Was New

John Haberin New York City

Ileana Sonnabend: Ambassador for the New

Jasper Johns: Regrets

I was late getting home from a studio visit way south in Brooklyn, because the artist was delayed on the way from the art fairs. And that started a lively conversation.

Now that art never stops, was the destination worth the detour? Step into a fair booth or an upscale gallery, and one could be almost anywhere, amid much the same cast and much the same international style.  The very name Miami Basel speaks not to a place, but to a global scene. Surely you are above that mix of media, of casual realism and gestural abstraction, of extraordinary polish and a determination to shock—all on an ever larger scale. And surely things were different fifty years ago, when Ileana Sonnabend made herself "ambassador for the new." No doubt, but one might have second thoughts after a show at MoMA of that very name, a tribute to her as dealer that looks curiously like art today.

The very name Miami Basel speaks not to a place, but to a global scene. Surely you are above that mix of media, of casual realism and gestural abstraction, of extraordinary polish and a determination to shock—all on an ever larger scale. And surely things were different fifty years ago, when Ileana Sonnabend made herself "ambassador for the new." No doubt, but one might have second thoughts after a show at MoMA of that very name, a tribute to her as dealer that looks curiously like art today.

Meanwhile Jasper Johns sends his regrets. Not that Johns, whose solo show opened Sonnabend's Paris gallery in 1960, has failed to put in an appearance, although one can search high and low without success for his outline. Still, he leaves more than a trace. The thirty amazing objects of "Jasper Johns: Regrets" take a single image through its paces, in pencil, watercolor, ink on plastic, aquatints, monotypes, and two paintings. He even displays the copper plates for several prints. He is just wary as ever of saying too much—or of leaving anything unstated.

Ambassador for Soho

MoMA honors Ileana Sonnabend with a double portrait by Andy Warhol, as he turned more and more from death and disaster to flattery and celebrity. A plank by John McCracken leans against a wall, as it did so often back then, while bathers by Roy Lichtenstein and Tom Wesselman add a touch of glamour and pop culture. Piero Manzoni's sealed metal drum holds a thousand meters of ink on paper, but it could just as easily have once again held his own shit. A violinist's grating repetition of a few bars from Igor Stravinski, thanks to Jannis Kounellis, hardly disrupts the Greek artist's soothing oil on canvas. Bernd and Hilla Becher set out their gridded photographs of a vanishing industrial landscape. Something blurry plays out silently on video, and it takes patience (or the wall label) to realize that Vito Acconci lay under a gallery floor, jerking off.

You may look to the past for an age of "slow art," but you will recognize the formula from today. At least you have every right to think you do, in a show that ends chronologically with Jeff Koons. Yet Sonnabend was taking chances every step of the way, just as she did in bringing Robert Rauschenberg, who first exhibited among friends at Betty Parsons, to Leo Castelli's gallery before starting her own. She opened her Paris gallery to introduce the new American art to Europe. And she opened her New York gallery in 1970 as an ambassador for Arte Povera in America, like the "igloo" of slender insect-like legs by Mario Merz or the "living sculpture" of Marisa Merz. She kept up with the Pop Art of Claes Oldenburg and James Rosenquist, the Minimalism of Robert Morris and Mel Bochner, the LA conceptual art of John Baldessari, the Neo-Expressionism of A. R. Penck, the blend of cartoons and abstraction in Carroll Dunham, and much else along the way.

If art like this could be anywhere, Sonnabend had long been in transit. A photo album by Christian Boltanski speaks implicitly to his father's trials in hiding from the Nazis, but for Sonnabend it might have testified to her and Castelli's plight as European Jews. As Leslie Camhi argues in a catalog essay, Sonnabend was truly at home only in art. Born in 1914 in Bucharest, she was seventeen when she married Castelli, and they escaped Europe by a most circuitous route. Castelli opened his gallery in their living room on the Upper East Side in 1957, two years before their divorce—and they helped make Soho an art scene on a September day in 1971, when their galleries, John Weber, and Andre Emmerich opened together at 420 West Broadway. It must have been quite a night.

MoMA insists on Sonnabend's independence. Ann Temkin, curator with Claire Lehmann, places her in a line of such pioneering women dealers as Peggy Guggenheim and Betty Parsons. Not even Camhi mentions Ivan Karp, a force for Pop Art at Castelli's gallery in the 1960s and then at OK Harris, or Paula Cooper, who preceded them all in Soho. A show of just fifty works devoted to an existing gallery sounds loaded regardless. One might mistake it for a plea for donations, like the gift from the estate of Rauschenberg's Canyon in 2011, with tax exigencies for the estate and conditions attached that included this very show. That combine painting, its stuffed eagle still soaring above a pillow suspended like testicles, looks far too cramped as the centerpiece.

The show feels oddly like business as usual for a woman who put art above business. Her father's money backed Castelli's first gallery, in prewar Paris, and she sold work that she had collected to keep her galleries and her artists alive. Still, Gilbert and George in their suits, like Michelangelo Pistoletto's cut-paper couple against mirrored steel, anticipate Chelsea's crowded elegance today. Haim Steinbach's black ceramics, a polyurethane animal by Peter Fischli and David Weiss, and Ashley Bickerton's Tormented Self-Portrait in corporate logos and leather—they and more anticipate its irony and its chill. Even Bruce Nauman with his neon and histrionics, Terry Winters with his watercolor Schema, and Jan Groover with her gorgeous still-life photographs feel the weight of the present. They also make me think of a later ambassador for the new, in fiction.

In The Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushner's novel about fatalism and promise in the mid-1970s, an artist leaps from motorcycle gangs to Minimalism and from Soho to Rome. For all the energy of the prose and the coming-of-age narrative, she portrays artists and dealers then as into one thing, attitude. If that sounds more like LA in the present, the author is young and lives there. Did Sonnabend's generation precede art's globalism, refuse it, or usher it in? Is there a point in looking back?

Johns sends his regrets

That single image in Regrets belongs to Lucian Freud, the German-born British painter—or perhaps to Jasper Johns, to Francis Bacon, to its photographer, to anyone who looks, or to no one at all. Bacon commissioned John Deakin's photograph of Freud around 1964, as a source for his paintings. Jasper Johns in turn came upon it in an auction catalog in 2012, the year after Freud's death. He thus connects two English artists known for their effusive agonies and their adherence to representation, while appropriating them for an art that refuses both. If one has been following or bemoaning the record auction price for Bacon, one may suspect Johns of doing the same, but of course he is not saying. His place in the art world hovers over the series all the same.

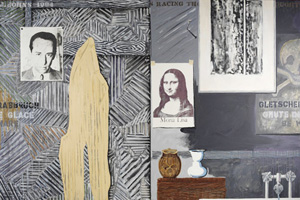

At least since the death of Rauschenberg in 2008, he has every claim on the status of greatest living American artist. Born in 1930, he must also know that he will not be that forever. And reflections on his career have long entered his work, as in the studio interior of Racing Thoughts in 1983 or a 2015 video of his garden by Mary Simpson. From the first, though, he has multiplied a handful of images in a hall of mirrors. A ruler hanging motionless against the area that it might have swept out, a target held uncomfortably in one's face, three flags superposed, or a map with its boundaries as fluid as encaustic and oil—they all reflect on their own making without quite admitting that it took an artist to make them. They are only what they are and more.

At least since the death of Rauschenberg in 2008, he has every claim on the status of greatest living American artist. Born in 1930, he must also know that he will not be that forever. And reflections on his career have long entered his work, as in the studio interior of Racing Thoughts in 1983 or a 2015 video of his garden by Mary Simpson. From the first, though, he has multiplied a handful of images in a hall of mirrors. A ruler hanging motionless against the area that it might have swept out, a target held uncomfortably in one's face, three flags superposed, or a map with its boundaries as fluid as encaustic and oil—they all reflect on their own making without quite admitting that it took an artist to make them. They are only what they are and more.

With Regrets, things are murkier than ever and yet no less literal. Even in black and white, Johns sees shades of gray, but then Jasper Johns in gray often has colors as well. The largest work in his new show, a painting, develops its gray through a great deal of color. As so often, Johns combines a found object with its mirror image, to create a semblance of symmetry or a disguise. Is the somewhat lighter gray surrounding a darker area just off center a veil, and is the space just above the darkness a skull? Is the word regrets, in cursive off to one side, the artist's signature, or is he sending his regrets? In time, one can make out Freud's presence or maybe absence, but it sure helps to go back to the photograph.

In time, one can make out Freud's presence or maybe absence, but it sure helps to go back to the photograph. Bacon being Bacon, the Brit preferred Freud seated in bed, nearly doubled over, with his hand to his face as if unable to face the camera or to bear his very existence. And Johns being Johns, the artist of In Memory of My Feelings, he chose a reproduction long since cracked, crumpled, paint spattered, seriously cut off, and folded back. Any jagged edges come with the image. As for the word regrets, he at some point had a stamp made so that he could dismiss more quickly myriad invitations to appear. Still, the word looks handwritten, and he does send his regrets.

The skull, the grid, the image of Freud, and their reversals come and go throughout the show. Johns displays each state of a print, as distinct as for Paul Gauguin, leaving it to the viewer to decide whether he is revealing his process or denying the very possibility of progress. One print includes directions to the printer to enlarge the stamp, and a separate series, of the numbers 0 through 9, bears the imprint of a mesh, rags, coins, and string. They are like a sign language that conveys nothing but the artist's hand. A pencil drawing after Freud also includes the words Goya? Bats? Dreams?—a reference to The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, an etching by Francisco de Goya among Goya's last works. Does it matter that Freud never gets out of bed, that Johns approaches art like a logic problem, that this may be among his last works, or that the words are a series of questions?

Johns takes each and every technique and runs with it. Ink can run or gather, pastel on charcoal on watercolor can take on unexpected textures, and the white of an aquatint can glow like neon while the black can resemble a cylinder lamp. He still juggles the twin impulses of late Modernism—from conceptualism to subtle abstraction and from a denial of authenticity to a space for personal expression. Can those two sides get along? The sources of Regrets do not connect all that closely to everyday life, and the stamp and the photograph do not have all that much to do with one another either. Still, it takes a virtuoso to send these regrets.

"Ileana Sonnabend: Ambassador for the New" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through April 21, "Jasper Johns: Regrets" through September 1. Related reviews look at Johns in retrospective and Johns through his "Catenary" series and Jasper Johns in gray.