The Ceremony of Innocence

John Haberin New York City

Jules Tavernier and Karl Bodmer

Surely Native Americans had suffered enough. They had retreated or died in the face of war, colonization, and disease. And the demands on their land only increased with the coming of the gold rush in 1848 and the transcontinental railway in 1869.

The demand was there for images as well—not of conquest, but of the wonders of the American West and its indigenous peoples. It brought Jules Tavernier and Paul Frenzeny to the camp of Red Cloud, in Wyoming Territory, on commission from Harper's Weekly. By 1874 they had made their way to San Francisco, where Tavernier received another commission, from a banker, to head for Clear Lake, just east of today's wine country. He was dedicating himself more and more to painting anyway, in search of not just new lands and new customs, but of himself.  He found them both in 1878, in Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse. For him, as for the Elem Pomo people, the ceremony stood for world renewal.

He found them both in 1878, in Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse. For him, as for the Elem Pomo people, the ceremony stood for world renewal.

Tavernier was not the only Swiss-born artist finding new opportunities in contested territory. Karl Bodmer was barely into his twenties when he caught the eye of a prince. He had a budding reputation for his river views in and around Koblenz, in Germany, where he had moved from Switzerland, but Maximilian had grander ideas. Back from Brazil, where his work as a naturalist opened European eyes to its native people, the prince proposed an expedition up the Missouri River. Bodmer was years away from his work with the Barbizon school in Paris, but Maximilian found a quick study and willing traveler. They landed in Boston on the Fourth of July, but they were looking beyond white America.

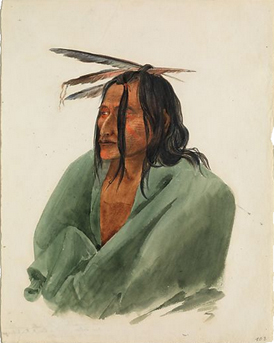

Bodmer's portraits of Native Americans are even now an essential record, in a way that those of another immigrant, Winold Reiss, are not. On loan from the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, they offer a pointed contrast to the westernized paintings and period furniture in the American wing of the Met. Just over forty works on paper describe individuals, but also a way of life. Tavernier, in contrast, rarely goes one on one with his subjects. He paints villages and rituals, like the mfom Xe (or "people dance"), and towering landscapes empty of both. He revered what he saw, but did he bring a morally innocent eye?

Subterranean fire

One might ask that about the public for his work as well and about Western art. Others have seen images of women and other cultures as acts of predation. Native American artists like Kent Monkman and Jeffrey Gibson do their best to reclaim their history. With Jules Tavernier, though, good and bad guys are not so easy to sort out. As leader of the Oglala Lakota, Red Cloud was among the few to have defeated federal troops, but Red Cloud Agency in Wyoming had federal supervision, and Tavernier got there under cavalry escort. Just as important, he was drawn to customs that merge participants and onlookers.

Even apart, Tavernier felt himself in the midst of things. It was a hallmark of Romanticism in literature and art—the observer as creator, and for him that imperative was altogether personal. On paper, he pictures himself at his desk, absorbed in his work, just as on canvas he pictures himself in the vastness of nature. Like J. M. W. Turner, he pictures nature, too, at the center of the action. He prefers sunrise and sunset, for the glow on the horizon and at the very center of the canvas. It rises to a crest, like a triumphal arch or ceremonial fire.

Not for him another and, in the end, finer Romanticism, Bodmer's translucency and precision. Tavernier builds his scenes from stroke after stroke and daub after daub. He values sunrise for its enveloping haze and sunset, for its long horizontal streaks in the darkening sky. They and the verticals of tall cliffs, as in his later trip to Yosemite, frame the action. Trees merge with clouds while a full moon breaks through, for a sense of awe touched by danger. One can feel the cold air.

He brings the same touch to indigenous America. In Village at Dawn, tepees supply the verticals and the gentle diagonals of linear perspective. For the underground chamber of the ceremonial dance, a slit in ceiling interrupts the darkness, far outshining a distant window and small fire. Now the daubs become people, in the very same reds and yellows as at sunset. They form a swirling pattern as they assemble and move. Now they are the action, and their colors shift with the light.

Which are the participants and which the onlookers? An entire community takes part, whether dancing, standing, or seated. So, for that matter, do visitors like Tavernier. His patron, Tiburcio Parrott, is among them, as is Parrott's business partner from France (and recipient of the painting), Baron Edmond de Rothschild. The Met fills out a small exhibition with headbands, jewelry, and baskets, most notably by Clint McKay. Like the dance, they have at once a functional and ceremonial role, in ritual washings. Their geometric patterns and construction, interlacing or coiling, recalls the dance as well.

The show also includes photogravures of and by women, with their own quiet dignity. Yet here, as in landscape, awe cannot dispel the danger. The artist also witnessed a coming-of-age ceremony that entails physical harm. The curators, Elizabeth Kornhauser with Shannon Vittoria and Christina Hellmich of the de Young Museum in San Francisco, speak of "strategies of resistance and endurance," and there was a lot to endure. Tavernier himself moved on, still in search of himself, reaching Hawaii in the 1880s. He could look back on Clear Lake as a point of light in the subterranean dark.

A confluence of rivers

One can see how Karl Bodmer caught the eye of a prince. One may remember his precision and accumulated detail, from painted flesh and head gear to the treasured objects in a sitter's hands. They are far fresher than that sounds, though, thanks to the brightness of watercolor and graphite's softness but also crispness. The Met asks Native American artists and leaders to contribute some wall text, and one all but dismisses the work as "clinical" and "romanticized." Still, that paradoxical combination gets at the very strength of German Romanticism, like the work of Caspar David Friedrich. It could apply to John Constable and J. M. W. Turner in England or to Théodore Géricault in France as well—or to such future Barbizon painters as Camille Corot.

The show opens with two landscapes that recall their art more directly, even as the Brooklyn Museum rehangs its American wing with greater weight to Native American art and people of color. Bodmer sketched the confluence of rivers, because of its importance to trade, and tents where women were tanning hides, but one is more likely to notice the light and moisture in the air. In portraits, too, he is situating subjects both in their culture and in the moment. These are not casual sketches, for all their spontaneity. Most took two sittings. The dense handwriting in a page from Maximilian's journals attests to his quick but detailed attention as well.

They journeyed north and west from Saint Louis, starting in 1833, and their round trip took them a full year and five thousand miles. It covered tribal lands for the Plains nations, but with long stays at Fort Clark, in present-day North Dakota. Native American art now can hardly avoid tales of slaughter and appropriation, as with Monkman recently in the museum's Great Hall, although Melissa Cody proposes something more optimistic. The two travelers, though, found a welcome in native hospitality and offered a welcome in return. One sitter returned for a second portrait—and who knows how many sought them out for a first portrait as well? Each work was a collaboration, and wall text praises how the works "connect to our traditional ways."

They journeyed north and west from Saint Louis, starting in 1833, and their round trip took them a full year and five thousand miles. It covered tribal lands for the Plains nations, but with long stays at Fort Clark, in present-day North Dakota. Native American art now can hardly avoid tales of slaughter and appropriation, as with Monkman recently in the museum's Great Hall, although Melissa Cody proposes something more optimistic. The two travelers, though, found a welcome in native hospitality and offered a welcome in return. One sitter returned for a second portrait—and who knows how many sought them out for a first portrait as well? Each work was a collaboration, and wall text praises how the works "connect to our traditional ways."

Bodmer must have given his subjects considerable say in how they pose. The Met explains at length what they wore and what they carry. They must have explained much of it to him as well. He tried to see them as they wished to be seen, but not as mere flattery. Their faces are dignified but not terribly boastful. Formal portraits at the time dressed American leaders in the trappings of war, but without a wound. These people come in peace, but with the marks of war.

The museum stresses how trade and marriage cemented peace between tribes, and the big fur companies came as a source of wealth and not just a threat. One man wears a fashionable hat. A woman's props show her role as a healer. Nor is paint simply war paint, meant to inspire fear. It includes spots for every time a man was touched in combat, with larger circles to remember bullet holes. It is a proud but sad display.

Life had to have been fragile. The portrait of a tribal chief brings out his vitality and youth, but not even elders are all that old. Whites carried not just guns, but also germs. That one grudging wall label also praises Bodmer's record of life before a smallpox epidemic in 1837, but then cholera delayed his passage west from Boston. Blankets brought what relief they could from wind across the plains. And yet a red one, set against a life-like pelt and the white of the paper, could also stand for a colorful life.

Jules Tavernier ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 28, 2021, Karl Bodmer through July 25.