Where to Be Modern

John Haberin New York City

Winold Reiss and Kwame Brathwaite

Ming Smith in Harlem

What was all this about modern art? A century ago, Americans came to Paris to see for themselves. Europeans, though, could not stop talking about America, and a young German took them seriously. In 1913, Winold Reiss packed up and moved to New York.

He did not approve of what he saw. New Yorkers were so behind the times, he thought, "like Germany sixty years ago," and he set out to teach them a lesson. He had immediate success in poster art, not all of it for worthy causes, and he applied his skills to market himself. He promoted his studio as a school, although it may not have had many students.  It did, though, oblige him to reach out, and his instinctive outreach opened his eyes. From Harlem rooftops to midtown restaurants, he finally encountered Modernism—one of two encounters, along with Kwame Brathwaite, at the New-York Historical Society, while Ming Smith at MoMA adds a portrait of Harlem for today.

It did, though, oblige him to reach out, and his instinctive outreach opened his eyes. From Harlem rooftops to midtown restaurants, he finally encountered Modernism—one of two encounters, along with Kwame Brathwaite, at the New-York Historical Society, while Ming Smith at MoMA adds a portrait of Harlem for today.

Sometimes all a people can do is to plead for life. Black Lives Matter does, achingly so. Yet Black Power long before refused to plead for anything, and Brathwaite took it to heart quite as much as Smith even now. He had already taken up photography, with those around him as his subjects and a concern above all for dignity. He has not exactly entered the history books, but many of them did, and he was more than happy to put them first. They were, after all, first and foremost performers, and their chosen arenas were jazz and fashion.

From Harlem to the future

Looking back, it is hard to say whether Winold Reiss had found New York too modern or not modern enough. When he arrived at age twenty-six, he had not yet known what a later work called City of the Future. Red Studio, by Henri Matisse in France, was just two years old and languished in a suburban studio. Cubism was still a work in progress, and German art before the terrors of World War I was just starting to catch the buzz. Reiss had his German academic training, and it shows in everything he did. His faces have a compulsive detail and polish.

Was he ever "An Immigrant Modernist," as the show has it? It was the clash between the two influences that liberated his art, tradition and the modern. They brought him commercial clients, but also the urge to look beyond commerce to all five boroughs of the city. Work in advertising confirmed his need to communicate, and commissions included high-backed furniture as well. They immersed him in Art Deco, which guides the typography of his posters and the black curves of his wrought-iron gate. They taught him the fusion of art and design, long before the Bauhaus in his native Germany.

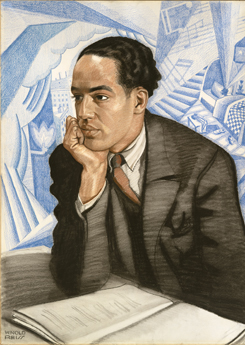

More liberating still was the face of other creative artists around 1925, starting in Harlem. He had a talent for mingling with talent, including Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, and Alain Locke, the philosopher of the New Negro and the Harlem Renaissance. Yet he treated ordinary people with the same precision and panache. You may distrust a white visitor as reveling in the exotic, unable to see through African American eyes. And he headed west as well, like Karl Bodmer from Switzerland before him, for Native American portraits. Yet he treated his sitters not as specimens, but as peers.

Reiss has real limits, as an academic and a "face painter," already half-forgotten at his death in 1953. He lingers over loose hairs, discerning eyes, and the texture and complexion of skin. And then he stops short, leaving much of the canvas sketchy or blank. He may reduce clothing to its outline in a single curve or the background to a near abstract fantasy in stippled blue. It may hint at a subject's concerns or not. If you did not know that Robeson was an actor, the others writers and activists, you would not find out from him.

The disjunctions turn on that collision between the traditional and the modern, and the casual finish loosens things up. What starts ever so academic comes that much more alive, and Reiss treats white sitters the very same way. One remembers the traces of a veil on his wife's flesh and the feather hovering over her head. Isamu Noguchi, so improbably young, cannot be bothered to tighten his tie. A girl's blanket veers on the decorative surfaces popular in art now. The most stylish of the lot is a librarian.

As curators, Marilyn Satin Kushner and Debra Schmidt Bach with Nalani E. Ikemoto devote the final room to his second career—as an architect and designer, from the Restaurant Crillion in Manhattan to the Hotel St. George in Brooklyn and the Shellball apartments in Queens. Here, too, Reiss had his contradictions. He has his allegiance to Art Deco, but his murals, now destroyed, depict ancient Egypt and the Middle Ages. He saw himself as helping to create public spaces, but with private property and emblems of luxury. Still, that golden city of the future, for Longchamps restaurant in 1936, is a marvel. As an airplane nestles into the New York skyline, dwarfing the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, he had at last become modern.

Black power in performance

Richard Wright wrote of black power in 1954, but it became a demand only later, as African Americans looked at the civil-rights movement and wanted more. Kwame Brathwaite turned to photography at barely twenty, and his small show rushes by in the space of just a few years, at the Society. He joined the Black Arts movement, which lasted just a decade after its founding in 1965, and helped found the African Jazz-Art Society and Studios, or AJASS, which staged concerts by Max Roach, Miles Davis, and Abbey Lincoln. Already, though, he was turning the spotlight elsewhere. He photographed a man smoking in a ballroom and musicians from behind. The houselights are lowered, but it is the audience that glows.

He sought out those who sought the spotlight, especially women. They pose in ostentatious jewelry, like its designer, Carolee Prince, herself. In no time, Brathwaite shifted to color, in a larger format, to close in on faces. Still, he had his group photos of fashion models, on stage and on pedestals, as a place to show off. They had their catch phrase, too, black is beautiful, and it, too, was political. They marched for it, picketing a wig supplier, and Brathwaite photographed the demonstration. They called for a more natural look, one that did not cater to white ideals of black beauty, and they called the style natural.

It must seem newly relevant today, a time of hopes for diversity in art. Museums look back to the 1960s for jazz photographers like Roy DeCarava—and black photographers like Ming Smith in the Kamoinge Workshop. They bask in tokens of glamour and identity, like Kehinde Wiley on his high horse. Whatever happened to irony and anger? Can one truly speak of natural and fashion in the same sentence? Brathwaite asked people to "think black, buy black," but was he already selling out?

It must seem newly relevant today, a time of hopes for diversity in art. Museums look back to the 1960s for jazz photographers like Roy DeCarava—and black photographers like Ming Smith in the Kamoinge Workshop. They bask in tokens of glamour and identity, like Kehinde Wiley on his high horse. Whatever happened to irony and anger? Can one truly speak of natural and fashion in the same sentence? Brathwaite asked people to "think black, buy black," but was he already selling out?

Not that he was above hard questions, unsettling to this day. He found his calling when a photograph of Emmett Till in his casket shook him up. Those who decried a painting after it in the 2017 Whitney Biennial as too white and too brutal should remember that the photo appeared in Jet magazine. Still, Brathwaite was slow to anger. He adopted the conventions of fashion as his own, even when it came to portraiture, politics, and jazz. In a double portrait with Abbey Lincoln, a young Max Roach looks like a supermodel himself.

Brathwaite may have felt the urgency of the moment, but he was always at ease. Born and bred in New York, like William Klein on the edge of Harlem, he was at home in the city. When he photographs the Marcus Garvey Day parade, the marchers might be just hanging out. When he attends a jazz concert on Randall's Island, the group photo looks thoroughly uncomposed. Roach on the drums seems in no hurry at all. You can hang out, too, on sofas of freestanding circular cushions, like a drum kit in black and white.

That is not to make too much of fashion photography. Nor is it to forget how often museums are selling out to the fashion industry, right down to street clothing by Virgil Abloh at the Brooklyn Museum. Still, the combination of ease and high style is provocative, and it conveys the politics behind the natural. So does the installation, curated by Aperture in collaboration with Brathwaite himself. His women were Grandassa models, after the writings of Carlos Cook, a black nationalist who referred to Africa as Grandassaland. A museum dedicated to New York has its own new-found land.

Harlem in a blur

Ming Smith picked a tough time to move to New York. Crime was beginning to rise, and hopes for an African American were past beginning to fall. The idealism and achievements of the civil-rights movement were harder than ever to maintain, and the hard science that she had studied at Howard University was not providing answers. The Harlem Renaissance that had drawn Reiss and Brathwaite was long past, although the music played on. Yet Harlem is where she came, and role models were all around her, in the arts and on the street. In her photos, it all went by in a blur.

Smith herself creates the blur in black and white. Not that she is lax in focusing the camera, and she does not always narrow its depth of field. A selective focus does play its part, suiting the isolation of a woman on a Greyhound bus or men in a crowd. Both in their way are looking for a way out of the loneliness. Yet a young man in a pool hall commands the room through her sharp focus and his cagy stance. Another takes the direct way down from a Harlem stoop while older men take their disciplined time, as Jump, and the camera gives equal attention to both.

But no, she cultivates the blur through long exposures and attention to light. Those and wild camera angles dare one to pick out men and women in a crowd, and the Million Man March and West Indian Day parade seem to take place at night. The spooky highlights piercing their mass could almost be artificial lights, like those in a shot of the Apollo Theater. They are haunted, like the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris or an isolated wood-frame house. They are haunted, though, not by ghosts but by the living that she came to know so well. She calls upon you, too, to acknowledge them—from immigrants dressed in white for work to a mother and child in a diner, Deciding.

They become actors in a drama and in seriously rough times. Duke Ellington on television shows his age, and an eerie cloud of light holds him at a distance from the TV screen. A Harlem sunset has its own breathtaking drama, carrying James Baldwin to the sky. An entire series picks up on motifs from August Wilson, a playwright. Still, they are all the stuff of life, famous or not. Smith has Charles Mingus, the jazz great, standing tall, but also kids, to judge by their white shirts and ties, in a school orchestra or band.

Long exposures convey the passage of time, and a drama has its narrative energy and direction, too. "The image is always moving," she says, "even if you're standing still," and one can easily forget that most of her subjects are at rest. One can forget, too, that her commitment to photojournalism is also a commitment to community. She makes a point of barriers between black and white when she photographs a man on the sidewalk with American flags behind glass. (It has its parallel in black women reduced to window shopping for Gordon Parks.) Still, MoMA omits that photograph and subtitles the exhibition simply "American."

Smith arrived in New York in 1971, and the black photographers in the Kamoinge Workshop invited her to join them the next year. Race and identity are at stake—but, as I wrote after Smith's photographs helped launch a black-run gallery in Chelsea, identity for her is tied up in mystery. The small show in MoMA's lobby gallery duly heightens the mystery. The curator, Oluremi C. Onabanjo, leaves some photos unlabeled, printed directly on the wall. Hung salon style, or all over the place, they contrast with the darkness and light of work in series, hung in a row. Identity as a matter of pride in art today will never be as moving or, ultimately, grounds for hope.

Winold Reiss ran at the New-York Historical Society through October 9, 2022, Kwame Brathwaite through January 15, 2023. Brathwaite died April 1, at age eighty-five. Smith ran at The Museum of Modern Art through May 29, 2023. A related article looks at Smith in the galleries.