Closing the Book

John Haberin New York City

Marcel Broodthaers and Warhol by the Book

Has any artist had a shorter and stranger career than Marcel Broodthaers? In 1964, at the ripe old age of forty, he created his first work of art from an edition of his poems. Meanwhile, someone else back then was moving away from a career in books—and not whom you may expect. First, though, Broodthaers and his poems.

Make that unsold copies of his poems, in a volume called Pense-Bête, their pitch-black covers half open and their pages scattering to the winds. The rough plaster and skull threatening to encase them forever have their ugly side, but also a resemblance to coral, its accretion a sign of life. And then in 1968 he declared himself an artist no more.  From the first, though, he had not given up on poetry, and at the end his art had only just begun. The more critical of the arts he appears, the grander his aspirations and installations. At the Museum of Modern Art, his life unfolds as one long, leisurely work of art.

From the first, though, he had not given up on poetry, and at the end his art had only just begun. The more critical of the arts he appears, the grander his aspirations and installations. At the Museum of Modern Art, his life unfolds as one long, leisurely work of art.

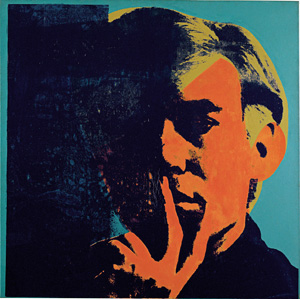

People often mention that Andy Warhol began as a commercial illustrator, but no one seems to ask: was he any good? With "Warhol by the Book," the Morgan Library has an answer. He was very good and, more surprisingly, not all that commercial. He was both skilled and childlike, savvy and happy to go along for the ride. He was a publisher as well as a creator, and he returned to books for their own sake when his need to work for a living was a thing of the past.

Breaking the mold

Others have died young, like Georges Seurat and Eva Hesse, or burned out in pursuit of a single idea. Marcel Broodthaers lived only to 1976, but he had a history along the way. The curators, Christophe Cherix and Manuel Borja-Villel with Francesca Wilmott, set aside a room for his poetry, in a retrospective of some three hundred objects. It could pass for the display of rare books and manuscripts at the Morgan. As a poet, Broodthaers had been fashioning a vocabulary, and later works weave it into hand-drawn text, much like a hero of his, René Magritte. Where Magritte declared that this is not a pipe, this artist draws pipes and declares that this is not a work of art.

Broodthaers lived in a bilingual country, Belgium, where he founded a gallery for just his work, but he never wrote in Flemish. As a poet who had carried messages for the Resistance and flirted with Communism, his first allegiance is not to a nation, but to language. He likes puns, both visual and verbal. While he does display a bone as Femur d'un Homme Belge, he dedicates much of those four years as an artist to mussel shells and broken eggshells, and the French for mussels, moules, also means molds. When he converts them into a black painting, like Christopher Stout or Tariku Shiferaw, he is walking on eggshells and breaking the mold. Moules frites, or steamed mussels and fries, is also pretty much the Belgian national dish, and when he paints the word veritablement, he is questioning not only the truth in painting, but also the painting or dining table.

He gave up art only to declare himself its curator. He spent the rest of his life on what he called the Musée d'Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, or eagles. And there, too, he was cultivating a vocabulary. It suggests royalty soaring to the heavens, but also the detachment of an artist not satisfied with the museums and platitudes of others. A poem had spoken of the "melancholy bitter castle of eagles," and he was prepared to maintain his own bitter redoubt. Rooms standing for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries contain decorative arts, but also weapons.

Still, irony would carry him only so far. He was friends with Joseph Beuys, and his imaginary museum looks ahead to the critical stance of a museum for Barbara Bloom and Postmodernism's "Pictures generation." Yet it identifies just as strongly with André Malraux decades earlier, looking to the entirety of art's past as a feast for the imagination. Broodthaers collects his favorites, like postcards of J. A. D. Ingres, and surrounds them with the trappings of French music and palm trees. He transfers to canvas the names of writers in English and German, from Oscar Wilde and Lewis Carroll to Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Nietzsche. For a true poet, text art can never be as bloodless as for Lawrence Weiner or John Baldessari in America.

Even his melancholy looks to the culture he wishes to preserve, like his filmed close-ups of collage by Kurt Schwitters. Besides Surrealism, his disjunctions derive from the classics of French poetry. He calls a poem "Le Voyage" after Charles Baudelaire, finds his role as a trickster in turning the pages of a fable by La Fontaine, and the sadness of his verses or a black coffin is straight out of Paul Verlaine or Arthur Rimbaud. He highlights the spatial character of broken lines in Stéphane Mallarme by effacing them in black. He is paying tribute to poetry as art or poetry in art, while placing it, as deconstruction would say, "under erasure" (in French, sous rature, or more literally crossed out). A "visual tower" of ceramics painted with eyes suggests a poet's or an artist's vision, but also a serious distrust of the all-seeing eye.

A personal vocabulary can look at once too impersonal and too private, like a work familiar from MoMA's collection, a white cabinet and table laden with eggshells, and maybe he had limits as an artist after all. Yet Broodthaers at his closest to poetry looks both ways, caught between love of the past and fear for the present. Pense-Bête means a memory aid, but as a wedding of thought and a wild beast. La Problème Noir en Belgique ("The Black Problem in Belgium") savages his country's colonialism with black skulls and a newspaper clipping from Le Soir (literally "the evening") about the Congo—but then his work, too, is painted black. His museum is an assault on commerce in art and the originality of the avant-garde, as with screen prints of gold bars captioned copy and imitation. Still, I bet he liked mussels.

Children's books for grownups

Everyone knows The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (from A to B and Back Again), and everyone knows how much Andy Warhol liked to collaborate with others at his New York studio, the Factory. Few know, though, that one student project at the Carnegie Institute of Technology was both a book and a collaboration, with Philip Pearlstein. On moving to New York in 1949, he found work in publishing as well as advertising and fashion, with some notable successes. He won an award for a wrap-around cover design, and he pushed design in the direction of an artist's book as well, with gold broken by black that slowly takes on the shape of a young man with a cigarette. That book was his own, in 1957, and he quickly turned to self-publishing for work with friends, from rhymes to a cookbook. You might have to settle for self-publishing, too, if your title was Wild Raspberries and your recipes included an Alf Landon salad.

It might comfort struggling artists to know that he received his share of rejection letters at that. One, addressed to "Miss Andie Warhol," found his work unsuitable for a publisher of adult books. And that early collaboration with Pearlstein, the future photorealist, was about a Mexican jumping bean. Warhol's covers often look like children's books, even when the cherubs perch on a bar glass and look decidedly erotic. Titles like Love Is a Pink Cake or 25 Cats Named Sam and One Blue Pussy pretty much give the game away. But then one of his very last books, a record of the party scene, was called Exposures.

It might comfort struggling artists to know that he received his share of rejection letters at that. One, addressed to "Miss Andie Warhol," found his work unsuitable for a publisher of adult books. And that early collaboration with Pearlstein, the future photorealist, was about a Mexican jumping bean. Warhol's covers often look like children's books, even when the cherubs perch on a bar glass and look decidedly erotic. Titles like Love Is a Pink Cake or 25 Cats Named Sam and One Blue Pussy pretty much give the game away. But then one of his very last books, a record of the party scene, was called Exposures.

The notions of commercialism and self-exposure may seem at odds. Lovers of Irving Penn look to his "personal work" as an antidote to his photographs for Vogue. Yet the combination makes sense for an artist like Warhol, who lived much of his life in public. As he wrote in Exposures, "I will go to the opening of anything, including a toilet seat." He came close to ending his life in public, too—the subject of I Shot Andy Warhol. The Morgan includes a photo of him in bed, beneath a cross on the wall, after the shooting, perhaps a hint to Warhol's religion.

People mention Warhol's commercial work so often because it seems to hold the key to his fame, for admirers and critics alike. After all, no one remembers Jackson Pollock as a former janitor at the Guggenheim. Warhol brought commercial images into Pop Art, no mean feat, and pundits like Robert Hughes have blamed him for selling out. Painters may still blame Warhol's influence for the course of art ever since, despite his brilliance and despite the profound influence of others then, like Robert Rauschenberg. Yet his book art is both sincere and personal, with hand-colored and handwritten designs—and it grows even more so after he breaks through. He even, at the end, threw in another children's book.

The show includes Warhol's early reading, such as Truman Capote, Gertrude Stein, and a volume on Henri Matisse. He took them seriously, too. A portrait has the sensual and laconic outline of Matisse books and cutouts. Other work from the 1950s has the stabbing black line of book design back then, but with a particular edge. Books from the 1960s have more color, but also a greater darkness. They could even rescue from familiarity some of his most repeated images.

His Marilyn Monroe becomes an accordion book bursting with color and all but leaving its subject behind. Jackie Kennedy fades to black, on the facing page from news bulletins of death, like a teletype feed in real time. The commercial world accepted Warhol, judging by a letter from Campbell's lending permission for a book image, "so long as our label is not used on a kind of soup." Still, as Arthur C. Danto argued, Pop Art refuses to distinguish itself from an actual Brillo box or soup can, and that is no small part of its subversion. It is careless in pursuit of pleasure, but also accepting of the consequences. As an early book cover has it, Warhol was always In the Bottom of My Garden.

Marcel Broodthaers ran at The Museum of Modern Art and "Warhol by the Book" at The Morgan Library, both through May 15, 2016.