The Talent Scout

John Haberin New York City

The motion picture screen . . . creates a boundary between audience and performer unlike any other in theatrical history.

— James Naremore

Warhol's Motion Pictures and The Talent Show

Spoiler alert: the first room of "Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures" does not hold Screen Tests. In fact, one of the films there shows an extended blow job.

I mention that because film reviews always come with spoiler alerts, I guess, but also because the seductive title Screen Tests fits so well. That may explain why an actual Warhol Screen Test has such a central position in "The Talent Show" at P.S. 1. It also explains why Warhol's brutal strangeness lingers, long after he became hardly more than a celebrity himself. He knew how easily the boundary of the motion picture screen could break, and the audience could become the performer.

Titled film stills

Each Andy Warhol film in that first room at the Museum of Modern Art amounts to an extended head shot, exposing its subject while he seems to do little more than kill time. (A smaller screen in a more modest spot by the entry runs a BBC documentary on their making.) The man in an overcoat and hat might be chewing gum for nearly three quarters of an hour, the man in front of a wall in the second throws his head back restlessly for just as long, and the third might have laid down to cope with eighty-six minutes of intense scrutiny. Each is doing something at once ordinary and elemental—indeed, ambiguously so. One has only Warhol's word for it that the first is eating a mushroom, perhaps hallucinogenic, and the second receiving a blow job from an unseen fellow filmmaker, Willard Maas. Each scene, too, could be following a script that Hollywood discarded long ago.

The man in Blow Job might be running through his Jimmy Dean poses, and the man in Eat looks like a refugee from film noir himself—like a cross between Edward G. Robinson and Truman Capote. The mob might have gunned down John Giorno in Sleep, and the poet does have more than a passing resemblance to Robert Mitchum. One never does know when Andy Warhol is breaking ground or recycling the old, and one never knows, too, when it is safe to shake associations between glamour and death. Warhol clings to the literal, while adding titles and subtext at will. He shot his films at the usual twenty-four frames per second and projected them at only sixteen, presumably to enhance the moments of stasis and strangeness, but he cannot help claiming the latter speed as a throwback to the silents. Come to think of it, these films are intensely silent, although they once commissioned La Monte Young for a soundtrack.

The entire show of Andy Warhol began as an exhibition of the Screen Tests, in 2003 at the late lamented MoMA QNS, and they still provide both the frame and an intense center. It runs from 1963 through 1966, but much of it dates from a single year, after The Factory's opening on East 47th Street—in a building long since demolished for ordinary apartments at an address that no longer exists. One often hears how Warhol abandoned painting for the movies and television, fearing for his slide into celebrity commissions, and the series straddled the two. Ethel Scull, the collector, posed for some of his worst silkscreens, but one would hardly know it from her Screen Test out front. It blossomed into hundreds, including the twelve that run simultaneously in the largest room inside. Eighty-eight play in sequence online.

One thinks of Warhol's films as daring, cryptic, and interminable, like Empire, with its eight hours of the Empire State Building. In fact each Screen Test is clear as day and exactly four minutes long, not a bad feat of editing if one recalls the slowdown and does the math. Each, too, is a collaboration that stops just short of a confession or revelation, much as for a young Warhol as illustrator. Allen Ginsburg never plays the prophet, while Susan Sontag has a critic's unblinking stare, but also sensual, masculine features that recall Mick Jagger. Dennis Hopper keeps shifting pose, as if begging for recognition as the next alienated young film star. Others purse their lips, play with their hair, or just do their best to stay still and alive.

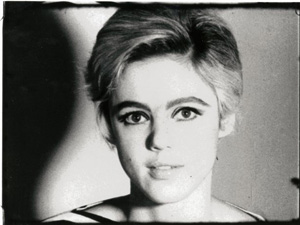

One can see them all in just four minutes, if one can resist several viewings, but it feels like a nice decade. The selection includes Lou Reed and emblems of the Factory years like Nico and Edie Sedgwick, Warhol's "charismatic ermine queen" (to quote Patti Smith). Nico's clip flits between close-ups of her features, but Warhol endows Sedgwick with the greater star turn. Her slightly parted lips will have to do for a symbol of the 1960s, on its way from a still marginal art crowd to a more selective club scene. His contribution to "1969" at P.S. 1 last year still looks daring, although by then he had largely relinquished directing to Paul Morrissey and his subject matter to porn. When Warhol returned to painting and taping, they had descended into verbosity and celebrity sellout.

One can write off Warhol easily enough or blame him for the 1990s, but at the cost of forgetting. He was friends with Jonas Mekas, the critic and filmmaker, and his Screen Tests alone hover over everything from Cindy Sherman, with her Untitled Film Stills, to Alex Prager's face-front Film Stills recently in the galleries for new photography. Experimental movies were just hitting their stride in 1963, well before Paul Sharits or Michael Snow and Wavelength, and not one of Hollis Frampton's from those years survives. Warhol also refuses the literary and epic baggage of them all or of Stan Brakhage before them. He is after something that will not turn its back on the life or culture in front of him, whether it fits into four minutes or, by the time he is done, five hundred times that. The museum plays fair when it closes Warhol films with Kiss, in a room furnished with actual theater seats without a riser—naturally enough, recycled.

A star is bored

In the future, Warhol said, everybody will be famous for fifteen minutes—but that was more than forty years ago, and Robin's intense, wordless minutes are still with us. At barely four minutes, her Screen Test, like that of Paul Thek opening his recent retrospective, could serve as a trailer for Warhol's films at the Modern. Indeed, "The Talent Show" marks the descent of P.S. 1 into MoMA Lite. There it follows "Greater New York," the museum-wide display of emerging artists and art's most heralded talent show. It all comes down, though, to a young woman's trembling lip stretched out to just sixteen frames per second. And the ironies aside, Robin's minutes really are past, for so little about her is known.

As always, Warhol is both art's finger to the wind and an enigma, at once dispassionate and sympathetic. He wonders at how much culture can encompass and how soon it can forget. Would he have appreciated that the Brooklyn Museum followed its window on late Warhol with the winner of art's reality TV show? I like to think that he would have been reluctant to play judge rather than interviewer, but also embarrassed for both the artist and the museum that they exceeded their fifteen minutes. "The Talent Show," organized by the Walker Art Center, invites participation and invades a subject's privacy, and it sees those impulses as inseparable. Perhaps, but after Robin how little it remembers.

One enters in winter by the building's original school front, while the museum renovates its bare concrete courtyard. Strangely, too, the show shares the first floor with Feng Mengbo's mural-scale video game of a Red Army soldier, which fondly recalls the clumsy pixilation of Pac-Man—not to mention such trite imagery as explosions, Godzillas, astronauts, and Coke cans. Mengbo also invites viewer participation even as almost no one gets to touch the wireless controller. The exhibitions also come soon after the Web as spy cam in "Free" at the New Museum, art as a torture chamber for Jill Magid or Kate Gilmore, performance as a work for hire for Marina Abramovic, an installation as a visitor's interrogation for Tino Sehgal, and the Lower East Side as an endless audition for Alix Pearlstein. Artists have been treating conceptual art as democracy since at least Fluxus, video as scrutiny since at least Gary Hill, and the male gaze as a nasty problem since at least the "Pictures generation." One will find none of the above at P.S. 1.

One enters in winter by the building's original school front, while the museum renovates its bare concrete courtyard. Strangely, too, the show shares the first floor with Feng Mengbo's mural-scale video game of a Red Army soldier, which fondly recalls the clumsy pixilation of Pac-Man—not to mention such trite imagery as explosions, Godzillas, astronauts, and Coke cans. Mengbo also invites viewer participation even as almost no one gets to touch the wireless controller. The exhibitions also come soon after the Web as spy cam in "Free" at the New Museum, art as a torture chamber for Jill Magid or Kate Gilmore, performance as a work for hire for Marina Abramovic, an installation as a visitor's interrogation for Tino Sehgal, and the Lower East Side as an endless audition for Alix Pearlstein. Artists have been treating conceptual art as democracy since at least Fluxus, video as scrutiny since at least Gary Hill, and the male gaze as a nasty problem since at least the "Pictures generation." One will find none of the above at P.S. 1.

A few artists give the viewer the spotlight, including a literal spotlight in an empty room by David Lamela. Piero Manzoni sets out the base of a statue marked with footprints (but do take off your shoes), and Peter Campus projects one's shadow on a screen. Shizuka Yokomizo asked people to pose in their front room and to set aside the curtain at a certain hour, while Philip-Lorca diCorcia photographed male sex workers avidly shunning the camera. Others more talented promise to reveal something of themselves—Tehching Hsieh as illegal immigrant, Hannah Wilke dying of cancer, and Chris Burden in his ostentatious disappearing acts. All that remains of You'll Never See My Face in Kansas City is a glass case with a ski cap. Still others offer themselves as signboards for a viewer's creations, but with strings attached.

For one thing, the artist gets title to the creation, which remains anonymous. For another, the offer does not extend to you, for the work's fifteen minutes of creation ended long ago. Most of all, the creations pay tribute to the talent show's lack of talent or imagination. Phil Collins prints other people's photos for free (in exchange for using them), Adrian Piper invites sketches from museum-goers, Amie Siegel collects bad YouTube performances (redundancy duly noted) of "My Way," and Gillian Waring asks people to pose as "pinups" (which a commercial artist has then repainted) or to supply her with a sign to carry around. Only the best of Piper's sheets ("Finally, legal graffiti," for one) allude to her concern for an African American woman's invisibility. Or, as Waring's poster says, "I signed on and they would not hire me."

The most radical work, as indeed for Andy Warhol, is also the most controlling, because only then can it test the limits of the artist's control. In 1968, with revolution in the air, Graciela Carnevale invited people to an opening, slipped out, locked the door behind her, and photographed their escape. By breaking the glass, they break not just the work's fourth wall, but also the artist's hall of mirrors. They seem less panicked than partying. And just last year Sophie Calle found an address book—and, by calling the people in it, tried to reconstruct the man it left behind, as if he were dead or a fiction. For all one knows, he was.

"Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through March 21, 2011, "The Talent Show" at MoMA PS1 through April 4.