The Real New York

John Haberin New York City

Civic Action, SculptureCenter, and Long Island City

You know the recipe: take a corner of New York, add artists, and stir. It sounds familiar enough, but is it always that easy?

The city is so much greener and more welcoming than in the 1970s, and artists and architects have done so much to extend that welcome. As the city was coming out of its darkest years, though, art did not exactly lead the way. Who would have asked it to try? Two institutions joined forces in 2012 to do just that for a sustainable future.  The Noguchi Museum, in collaboration with Socrates Sculpture Park, offers "Civic Action: A Vision for Long Island City." It comes across as more visionary than real.

The Noguchi Museum, in collaboration with Socrates Sculpture Park, offers "Civic Action: A Vision for Long Island City." It comes across as more visionary than real.

Two years later, SculptureCenter may yet anchor change. One of contemporary art's most overlooked institutions, it has long epitomized a neighborhood in transition. Now it has found a more lasting home in a revitalized Long Island City. Its fall 2014 reopening with "Puddle, Pothole, Portal" presents modest but pointed changes in its architecture. Could it be a model for New York? First, though, take a step back to the mid-1980s, before so much happened.

Civic inaction

P.S. 1 had opened in 1976 without much changing the Long Island City landscape. East Village galleries were to pack up and leave from almost the moment they caught fire. Soho was flourishing, but artists were already lamenting the loss of affordable lofts. If they had imagined Soho as a luxury shopping mall, much less artists as hipsters chasing themselves out of Williamsburg, they might have cried. Lincoln Center had literally turned its back on a community, and no one wanted another bare plaza. Modernism's ideal city had come to stand for failure or repression, and no one had the cash to build one.

In 1985 and 1986, two artists came up with their own Long Island City visions. Isamu Noguchi and Mark di Suvero might have been worlds apart, rather than a block away. The Noguchi garden museum opened to the public across the street from Noguchi's studio in Queens. A few months later, di Suvero founded Socrates Sculpture Park. It, too, has both work and display space, plus a Socrates Annual for artists in residence, and his own towering sculpture still anchors it to the waterfront. They offered two models for change—and two good reasons not to worry about it.

Noguchi had purchased a photogravure plant ten years before to display his work, and he brought to museum architecture the same quietude and perfection as in his sculpture. di Suvero, nearly thirty years younger, saw things in terms of community and as a work in progress. An heir at once of Alexander Calder and Calder mobiles, David Smith, Minimalism, and earth art, he knew what it means to leave rough edges in place—and what it means to encourage human traffic to add more. Industrial material or studio activity was something not to hide, but to display. And these visions co-exist today. As one walks more than half a mile to the foot of Broadway, one feels the isolation but also the community.

Gentrification is not the first word to spring to mind. In hardly a block from the subway, one leaves Astoria's coffee shops and bakeries (not to mention my dentist) behind. After a renovated school and a small shopping plaza dominated by fast food, one sees mostly emptiness, auto body shops, and scattered apartment buildings. Yet people make the trek all the time. The park has a Saturday green market, outdoor movies, and of course sculpture. For "Civic Action," Ben Goodward's fifty-foot arch of scaffolding encloses a black oil drums, like a rock concert stage as dump site.

One can credit art, but change was slow in coming after all. It took twenty more years for the Noguchi Foundation to register with New York as a museum. It still has few visitors, although all the more peace for that. Just a few summers ago, too, the scruffy sculpture park had little action. The undistinguished apartments look as if they went up barely yesterday, and mostly they have. Surely the biggest trigger, other than New York housing needs, was not art but the Costco right next store.

Lessons on the politics of architecture are easy enough to find, much as in any global megacity. Change comes on its own, and things work out in the end, but free markets do not serve everyone well. As it happens, "Civic Action" has all sorts of lessons, too—none of them clear either. As curator, Amy Stewart-Smith invites four artists and collectives to reshape the future, and they come up with fascinating visions. They also break with Noguchi, di Suvero, and the area's current evolution. They imagine Long Island City as a work of art all their own.

Astroturf and information

No one expects anything new from Rirkrit Tiravanija, and he delivers. The artist who cannot stop serving curry in upscale galleries imagines a "community kitchen." At least this time "menus will vary." He responds to community needs by letting spores arrive of their own accord that "perhaps . . . will be edible." He also proposes paving Broadway with "drivable grass." This is relational esthetics with no relation to its surroundings.

Natalie Jeremijnko, as in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, has more respect for her neighbors. Her salamanders receive "luxury housing" in Socrates Sculpture Park. People, unfortunately, must submit to a sterner regimen—one part environmentalism and ten parts fantasy. Women must wear "hot-rodded" high heels, families must grow their own food by hanging "urban farming systems" in AgBags out their double windows, and "feral robots" will relieve everyone of the need ever to get together. People will spread seed with hula hoops, and human flight will replace diesel trucks. As so often, going back to Noguchi's collaboration with Buckminster Fuller, futurism dates mighty quickly.

George Trakas sticks to old-fashioned landscape architecture. He proposes a shoreline walkway, uniting Broadway with the bridge to Roosevelt Island and Newtown Creek beyond. It will have the decency to serve "the people who live here now," while recalling an actual estate, Ravenswood, that served the wealthy almost two hundred years ago. It fits well with ongoing development near MoMA PS1, by the old Coca-Cola sign overlooking the East River.  It also translates into a piano (sporting Haydn's Water Music) with its innards leaning against a display table—like the piano that Harpo Marx destroys in A Night at the Opera. Still, the project leaves existing neighborhoods all but untouched.

It also translates into a piano (sporting Haydn's Water Music) with its innards leaning against a display table—like the piano that Harpo Marx destroys in A Night at the Opera. Still, the project leaves existing neighborhoods all but untouched.

Mary Miss has survived more visions than almost anyone. A pioneer of earth art, she proposed such welcoming urban designs as a pier off Manhattan's Battery Park. Now she hopes to enable "creative re-purposing" by others. Her museum display replicates the ghostly Con Ed stacks that tower over the waterfront like barber poles. In turn, she would make actual poles in the area into meters monitoring waste, water, and energy use. With luck, her "speech bubbles" and trucks as "incubator studios" will encourage conversation rather than prepare it for disposal.

It takes a little imagination even to call this Long Island City, so far from the Queensboro Bridge and a former Italian neighborhood to the south. It could be no more than a fantasy New York. Housing is at last beginning to flourish, but plans by Richard Rogers for the former Silvercup bakery remain unfinished. And it takes callousness never once to mention the Queensbridge low-income housing southwest of Astoria. In the real world, projects means anything but artist visions. Then again, Smith-Stewart will surely understand, for she has been in transit from her days as a curator at what was then P.S. 1.

These ideas range from beauty to self-parody. They do too much to impose on the area and too little to transform or protect it. Maybe it comes with playing visionaries. Still, they combine the best of a sculpture garden and a community park. They should inspire not just rezoning, but more museum displays like this. Wait and see.

Coming home to LIC

Founded in 1929 in the Village, SculptureCenter moved in 2001 from an Upper East Side carriage house to within blocks of what is now MoMA PS1, where it has paid host to such grand dames as Ursula von Rydingsvard and Petah Coyne—and to such bad boys as Mike Kelley and Michael Smith. Yet the Maya Lin architecture still looked in transit. One entered the former trolley repair shop past a roll-up gate along a dead-end street, a pebbled garden, and a desk that might have folded up for the night. And one found not just a great space, but also the raw materials for art. Its skylit interior, undivided but for a room behind the desk, leads to basement tunnels, their functioning infrastructure barely exposed to light. They seem only right for a city on the edge or on the verge.

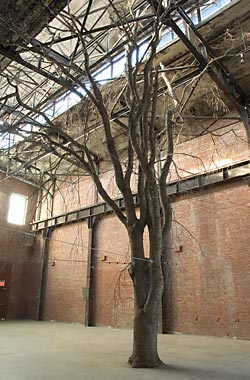

It has thrived, too, on its crumbling brick and adventurous choices. A tree by Anya Gallaccio blossomed easily in its main hall, who has settled at times for recreating Sol LeWitt, and Jeppe Hein reached for the skylight. Most often, though, one came for the surprises lurking below. One could delight in how the space shaped each and every show. Not that everything worked out as planned, only starting with its near secret identity. Who, for example, wants a large sculpture garden that never seemed to house sculpture?

Now the Center has reopened, in a changing Long Island City. The gate has given way to a door beside a proper wall, in rusted steel that a visitor could mistake for sculpture by Richard Serra. Within, more than half the garden has become a proper entry as well, with a desk and bookshop in the same white concrete as for PS1—thankfully, without tchotchkes for sale or a café. It also houses an elevator, as suits the tired, the eager, building code, and moving art. A partition marks out a broader entry to the main hall, with a further partition just behind for added wall space. For the reopening, the additional small chamber to its side held, thanks to Judith Hopf, concrete sheep and a glass door, with a hand-drawn knob to proclaim the new divisions.

Where once Ilya and Emily Kabakov created "The Empty Museum," the site now has occupants—and chipper ones at that. They include a model Superman by Danny McDonald, Lego-like robots by Keicchi Tanaami, vaguely scatological cartoons by Jordan Wolfson, hands grasping toilet paper by Lucie Stahl, Teresa Burga's stillness, and still more action figures in paintings by Jamian Juliano-Villani. Signs of others appear in Lina Viste Grønli's sports equipment pressed between bricks, Antoine Catala's motorized office junk, Win McCarthy's drooping glass sculpture, Olga Balema's latex "long arm," Camille Blatrix's steel tongue, and Marlie Mul's seemingly bandaged glass panels. The pebbled square of the remaining garden, too, has sculpted company for a change, including a tycoon, a dog, a humble laborer, and a military officer with a birdbath for a brain. Mick Peters may have the neighborhood in mind, still caught between waterfront luxury towers and the utter dearth down the street from the Center itself. Maybe he was thinking, too, of PS1's original function when he left a blackboard downstairs, with extravagantly oversize chalk.

They all belong to "Puddle, Pothole, Portal," curated by Ruba Katrib and Camille Henrot, who has filled a floor of the New Museum with her memories of Eden. Their global cast claims inspiration in "out-of-control machines" and Saul Steinberg, who gets the small room still in the back. The title means little or nothing, while the nearly two dozen artists add up to misplaced hyperactivity for so grand a space. Only Chadwick Rantanen aspires to scale, and his telephones hanging from piled desktops mark a failure to communicate. What do Joachim Bandau's layered rectangles in black watercolor have to do with all this? Probably nothing at all.

The real story remains the Center's future and a neighborhood's past. As architect, Andrew Berman has basically rearranged the elements with which he began. The brick façade has regained its industrial glory, although Allison Katz embellishes the windows over its tall arches, and the basement still has its ruins. More trash spins cheerfully past on a dry-cleaner's rack in one alcove, with help from Abigail DeVille. She calls it Gone Forever Ever Present, which pretty much sums up the dilemma of the present. I shall miss Lin's simplicity, but her rawness has found a more lasting home.

"Civic Action: A Vision for Long Island City" ran at the Noguchi Museum through April 22, 2012, with components on display on site in Socrates Sculpture Park through July, "Puddle, Pothole, Portal" at SculptureCenter through January 5, 2015. The Center reopened October 2, 2014.