Sculpture as Model

John Haberin New York City

Grace Knowlton and Erin Shirreff

Anya Gallaccio and Derek Franklin

If you want attention, consider filling a gallery with truckloads of dirt. But if you want to have a lasting impact, consider importing geology memory by memory and bit by bit. Grace Knowlton has been doing just that for more than forty years. It has kept her just under the radar, but deep within the consciousness of practicing artists.

It has also made her the subject of repeated rediscoveries. Review after review over the years has marveled at her neglect as if for the very first and last time. With luck, a survey of work since 1975 will serve as a prelude to a fuller retrospective. Like her art, it is comprehensive but not at all large, and it depends on juxtapositions across time and space as if they occurred just the other day.  Her sculpture has the look of weathered timber and raw earth, but with patience it takes on associations of craft and home. One can see a similar practice emerging in younger artists as well, including Erin Shirreff, Anya Gallaccio and Derek Franklin.

Her sculpture has the look of weathered timber and raw earth, but with patience it takes on associations of craft and home. One can see a similar practice emerging in younger artists as well, including Erin Shirreff, Anya Gallaccio and Derek Franklin.

Down to earth

Knowlton's show does not run chronologically, but then her art has not so much evolved as continued to find new expression. Born in 1932, she studied with Kenneth Noland, the color-field painter, but found herself sculpting spheres. They suggest both formal perfection and an evolving earth. She says that she relished her early ceramics as a "secret space closed off forever," but spheres also look outward to the universe. Six pieces from as recently as 2013 orbit a larger one from 1991 in polished steel. They range from closed spheres to one peeled back against the floor like Woman with Her Throat Cut by Alberto Giacometti, as if bursting apart.

Knowlton says that she first thought of sculpture as a surface for painting, much as for another woman in Minimalism, Rosemarie Castoro. In fact, she is still painting, in crossing arcs of black and white. Still smaller spheres have a surface of pinned white paper. All have visible imperfections attesting to time and the artist's hand. Their materials include bronze, iron, plaster, Styrofoam, glazing, and clay. Any one of them, though, could stand as well for fragments of planet earth.

Knowlton started getting her hands dirty as early as 1975, with what she calls Dirt Piles. They take the shape of volcanoes or lava flows, much like Robin Peck's weighty sculpture, and a painting from that same year appears in the process of erupting. The show's oldest Dirt Piles, a set of eight, rest just off the floor. One can treat them as distinct ceramics or a single work. Still others amount to loops of graphite on paper. They could be documenting the making of art or its instability.

Knowlton shares the gallery with a group show nurturing and savaging "Domestic Ideals." It, too, sets aside the big gestures, but not without a struggle. Joan Linder finds life at once small in scale and out of control, in a collage of bills and reminders or the unwashed crowding, meticulously drawn, of a kitchen sink. Marcie Revens has way too many possessions as well, in suitcases unready for her to unpack or to carry away. Katya Grokhovsky's clothing has taken on a comic life of its own, like the proverbial empty suit but for an independent woman, while Paul Loughney with paper collage weaves between closed spaces and an unmade bed. Ryan Sarah Murphy photographs suburban and New York neighborhoods as sites for looming dark silhouettes, but A-CHAN still cannot bring to an end the search for a "vibrant home."

Walter de Maria drew attention in Soho in 1977 with a literal roomful of dirt. It marked the shift from earthworks as subject to entropy and decay, like Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake, to today's childish displays and trashy installations. New York Earth Room led directly to The New York Dirty Room by Mike Bouchet and A Psychic Vacuum by Mike Nelson. The latter excavated beneath a gentrifying Lower East Side to reveal a hidden New York of his own making. Agnes Denes could still claim a connection between feminism and land art in 1982, with her wheat field in Battery Park City. Yet it gets harder and harder to reclaim public and private land for regeneration and growth.

Knowlton refuses nostalgia, but in order to reclaim space for everyday change. She has photographed sawhorses and chairs, added paint in response to the shapes and texture of wood, and rephotographed the results. She looks up close and corner-on, because the joints holding things together matter as much as what they support. Is she calling attention to her studio worktable as a construction all its own or as a place for art? Surely both, much as bronze floor pieces from 1986 redouble corners of the gallery. Either way, displacement and dirt need not preclude home.

Model building

Erin Shirreff infuses Minimalism with the elegance of Modernism, the strangeness of Surrealism, the coarseness of earth, and the fragility of flesh. Past work alludes directly to Post-Minimalism or Neo-Minimalism, with off-white, off-kilter sculptures resting against the wall, as in the Guggenheim's "Photo-Poetics." One might never know how firmly they balance, just as one might never know that their weight and hard-edged geometry derive from ashes. Her latest takes her beyond sculpture, to prints, photography, and video as well. It nurtures the texture of her materials while disguising their origins. She is model building, but with a greater and greater range of models.

One can assign them to five bodies of work. To call them mixed media would miss their plainness, but to call them plain would miss how much they keep one guessing. She titles the show "Arm's Length," in accord with their apparent detachment—in emotion, style, and even in time. Almost anything here could be left over from early Modernism, if only you could pin down where or when. Yet it all attests to contact between materials and the artist's hand. With surfaces like these, you may find yourself wanting to stretch out your arm, too.

The most allusive look like metal, in dark gray of more or less regular geometry. Thick rods and cylinders balance on one another and an equally dark tabletop, while other planes balance on them. They recall early modern still life, as for Isamu Noguchi or Constantin Brancusi, with their refusal of a pedestal. They could be architectural models on the artist's very own worktable. They are actually the show's sole mixed media, in fine, durable plaster mixed with graphite and assisted by an armature of steel.

Larger works really are metal, in much the same grays. Rather than piling up, they drop down like curtains, balanced on rods from above. They could be the heaviest and most jagged sheets that one will ever see. Shirreff patterns them, though, after cut paper, and some fold upward like paper as they reach the floor. Their elements also serve as points of departure for the remaining three bodies of work. Those works leave sculpture more and more behind as they introduce color.

Larger works really are metal, in much the same grays. Rather than piling up, they drop down like curtains, balanced on rods from above. They could be the heaviest and most jagged sheets that one will ever see. Shirreff patterns them, though, after cut paper, and some fold upward like paper as they reach the floor. Their elements also serve as points of departure for the remaining three bodies of work. Those works leave sculpture more and more behind as they introduce color.

Photograms on stretched canvas juxtapose rectangular fields of a ghostly blue. They are the direct impression of sculptural elements, but in two dimensions. They are also cyanotypes, a medium commonly used in architectural plans. Actual photographs of completed sculpture look like etchings in their rich, grainy brown but roll outward from the wall. Finally, a video slide show fills a large room with a compendium of shapes and colors. They conform to the actual architecture while recalling an earlier Czech Modernism.

Once Rosalind E. Krauss wrote of "Line as Language" and Yve-Alain Bois of Painting as Model, to give painterly gesture then largely in eclipse the requisite formal and conceptual detachment. Shirreff is still model building, while further downtown Pam Lins positively shouts "Model Model Model." Her three-word title notwithstanding, the show includes two series based on models some fifty years apart. One consists of Princess phones in MDF smeared loosely with old automobile colors, the other of ceramics modeled after Russian Constructivism. They make explicit the tug in Shirreff as well toward both art history and pop culture. The tug makes sculpture's languages both more gorgeous and unstable.

Reviving Minimalism

Anya Gallaccio might be acting only as curator, for a series by Sol LeWitt, but what then is that coarse black stone on the wall? Derek Franklin might be compiling an entire lexicon of Minimalism, for your edification and enjoyment. He has more seeming stone, too, strewn across the gallery floor like earth or flung lead. He has his own sculptural geometry, in open frameworks of galvanized steel. He has abstractions as well, somewhere between a studied monochrome and a rock face. So what then are the rusted bolts amid the rocks, and what lies within the glass jars on his dark metal shelves?

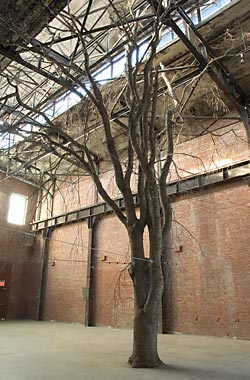

In truth, as Minimalists go, both artists are something of new-agers. Franklin's stark materials stand, he says, for "healing, abandonment, and revitalization." His show's title, "Mending Capers," sounds like a thankfully forgotten dance craze, salad dressing, or alternative medicine. Gallaccio has made a near fetish of natural materials, from flowers and chocolate to a tree in Long Island City. Both see their materials as the locus of a journey across continents and geologic ages, and they want it to become a viewer's personal journey as well. It just happens to unfold in the time and space of the gallery.

Gallaccio's floor pieces recreate LeWitt's 1974 Incomplete Open Cubes, each nearly four feet tall. Their edges pass through half a dozen permutations, in varying degrees of completion. Yet while LeWitt built his geometries from aluminum painted white, she starts with such native American materials as limestone, sandstone, and granite—their porous surfaces like particle board or ceramic.  The wall pieces are fragments of obsidian, their volcanic glass polished like black mirrors. The contrast between black and white looks back to Minimalism, while the mirrors look forward to you. She thinks of them all as a natural history of America.

The wall pieces are fragments of obsidian, their volcanic glass polished like black mirrors. The contrast between black and white looks back to Minimalism, while the mirrors look forward to you. She thinks of them all as a natural history of America.

Franklin's floor piece, Charnel Ground, refers, he says, to "a Tibetan funerary practice in which the bodies of the dead are left on a mountaintop to naturally decompose." Fortunately, they are not going anywhere fast. They adapt admirably to the architecture, spilling out from the connecting corridor into the broader back room. They also introduce the human element of their making, in a way that Richard Serra would understand. Serra called his flung lead Castings, although no pun intended. Franklin, in turn, has cast these gray stones from concrete, in shapes like tear drops and with a nod to Jean Arp.

Other work continues the ambiguity between industry and nature. Steel functions as shelving, and jars hold gin-soaked raisins that could themselves pass for stone. The abstractions are inkjet prints, based on scans of Norman Rockwell, with asymmetric white borders that defy formalism. Never mind that golden raisins, too, are a purported natural remedy—or that a second steel sculpture supposedly recalls a "therapeutic tub."

Installation art and Minimalism dissolved the boundaries between the sculptural object and the gallery, while conceptual art and earthworks dissolved the boundaries between the gallery and the world. Now, retreads can be yet another symptom of today's Neo-Mannerism and "zombie formalism," much as in painting. Gallaccio really could just be trotting out an expensive private collection. And, yes, others have already excavated the Lower East Side. Yet all these artists know when to leave behind the formalism. They talk big, but the art still sticks to the nuts and bolts.

Grace Knowlton ran at Lesley Heller through March 8, 2015, Robin Peck at Canada through March 29, Erin Shirreff at Sikkema Jenkins through May 22, Pam Lins at Rachel Uffner through May 31, Anya Gallaccio at Lehmann Maupin downtown through February 15, and Derek Franklin at Thierry Goldberg through February 22.