Between Art and Words

John Haberin New York City

Fifteen Years of haberarts.com

Somehow, it keeps coming down to words. Strange, no, when art is rarely just text—and never just an argument.

Once I spoke on a panel devoted to "the handmade." Has anyone spent time with group shows and open studios filled with dreary, derivative painting? Is that seriously the answer to bloated, trashy exhibitions? And can anyone call the latter conceptual art, when it has hardly an idea in its head? My answer had three parts: celebrity drives those big shows, money drives celebrity, and it will take art rich in ideas and feeling alike to break their hold.

Luckily, I had a second chance to get it right. I also contributed to an online panel, on the subject of "complicity." Is art trapped by a corrupt system, or can art and ideas break free? No, I answered, to both. Overt protest, formalism, and working within constraints—what I jokingly called explicit, implicit, and complicit art. All thus have their risks, and all have their place. And, sure enough, the loudest reply changed topic entirely, to my use of critical theory for vocabulary.

I shall ask what went wrong. In the process, I want for a change to defend other critics and other practices. I cannot help, though, putting in a word for my own. After more than fifteen years, this site is huge. To show how it grows, I also add a look at a single exhibition, to suggest my evolving goals. Related articles laid out a first "preface to criticism" at the start and what my own retinal surgery taught me about art and vision.

Working in the gap

This site often returns to why art takes words and not just looking. Looking does not come naturally, especially after Modernism, and art history quickly fades into memory. That is why museums nudge responses with controversial attributions, wall labels, and press releases. That is also why so much art aims for show, at the expense of feelings and ideas. When a show starts to look hollow or corrupt, as with a private collection at the New Museum or Jeffrey Deitch moving from Soho dealer to museum director, follow the money. There is a lot of it to follow.

Nor does it help to single out for blame those ideas often called critical theory. Theory has made its contribution to understanding art, and it has inspired some decent art as well. Besides, when ideas grow stale, artists may deserve some of the blame—for not creating work that turns ideas inside out. This is a not a bad time for making art, with everything from photography and realism to abstraction in the mix, but diversity means drift as well. And there, too, markets play a role. They are always looking for the latest thing.

No one should have to defend philosophy, as if mainstream journalism did any better in reducing criticism to superlatives. It hardly began with the 1970s either. I may often lean on Jacques Derrida or Hal Foster, but mostly because they are alive for me today. One can argue with critics, just as one can argue with Plato, Kant, your friends, or me. However, that should never mean demonizing them. And, again as with Plato or your friends, once you start an argument, you may lose.

Of course, academic discourse is stuck in its own rut. No one needs another student paper comparing the treatment of women in Henry James and Charles Dickens. Still, the discourse has helped artists, too, to pose questions. When Jennifer Dalton and William Powhida open a window onto the art world, they parallel the growth of museum studies. Other fields have felt the same pressures, and a good thing, too. International relations, for one, must now consider constructivism, Marxism, and feminism alongside the old poles of liberalism and realism.

Theory sounds impressive, but the divide between scholarship and ordinary criticism has never been greater. And that divide has terrible consequences for art. Even just before October magazine, artists turned avidly to writers like Robert Smithson, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, Meyer Schapiro, Michael Fried, Arthur C. Danto, Tom Hess, Lucy Lippard, Joseph Masheck, and a dozen others as distinguished and committed to the artists they loved. Do magazines now look and read like advertising, and do artists worry more about who gushes about them on Facebook? One can blame the obscurity of theory for the divide, but then it gets hard to blame theory for art. And again money talks, by favoring criticism focused on thumbs up or thumbs down.

And that is why I write. I want to work in that gap between art and words, in a way that is accessible but informed. Thomas Hoving at the Met thrived on working in that gap. He showed that a museum that does not reach out fails as a public institution, while one that does risks commercialism. Then, too, elitism and popularity both have their merits. Picasso, for one, managed both, and he still gets people talking.

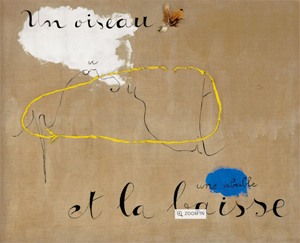

Me and Joan Miró

After twenty years, I still like to say that I do not blog: rather, I write about art. When I started this site, it did not even look like a blog. In fact, I had not even heard the term blog. It took a while before I added a home page for shorter, frequently changing items.

I still try not to write impulsively. I want an exhibition to settle in my head. I would rather write longer than more often, and I would rather not worry about passing judgment. I would rather finished items aside, sometimes for months, before looking at them again and rolling them out here. If I do not end up writing at all about some shows that I have enjoyed, because I have run out of things to say about them, the world will survive just fine.

I hate blogs filled with photos of exhibitions at the expense of insights. I hate the videos that begin with the blogger finding his way to the gallery, like the guy on the cell phone next to you making you listen to his progress toward the office. When I started, who knew that art would become this popular? Who knew that everyone would carry a camera everywhere to see it?

This once, though, let me describe how another review came about. Take an article near the close of 2008, about Joan Miró and his "Painting and Anti-Painting." I feel self-indulgent. I understand the hypocrisy of talking about myself in order to say why I do not talk about myself. It sounds like boasting. Maybe, though, it will continue an argument about what a webzine can contribute.

I left the exhibition happy. Gee, I thought, modern art really was lively back then. It was still an experiment in progress.

I knew Miró's work mostly from the Modern's permanent collection, including two works in the show—Dutch Interior, a fave, and Still Life with Shoe, far less so. I knew the later, postwar work, of open fields of color soaked into canvas. And for all their cuteness I had found the parallels to Abstract Expressionism striking. Gee, I thought, now I can see how it all fits together. This is what great exhibitions do: they get you excited about an artist, because they show you something that you had never seen before.

How critics provide context

I wanted to explain what I had seen to others. In other words, I had ideas in my head, and I wanted to share them with you. I did not have to insist that I liked the show, as if my taste matters more than yours. I did not need to insist either that I like Miró, as if textbooks and museums need my approval to treat him as a major artist.

Judgment can still emerge implicitly, from description and explanation. In fact, it can then be a lot more convincing. That is why art really does take words. It is why anyone studies art history—because facts, interpretation, and explanation all broaden one's judgment.

I had also read two reviews that left me demanding more, very much as Michael Kimmelman had so many years before, when I read his review of a show at the Brooklyn Museum. He got me to define very much in contrast my ideal criticism more than fifteen years ago. This time a terrific critic, Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker, dismissed the show. He found its shocks pale compared to those of the 1990s, and he complained that it would take too great an imagination to feel the impact that Miró once had.

To me, a critic's job is exactly that act of imagination. With it, work may come to seem familiar. Conversely, it can help older art recover its shocks, by giving the work a history and a connection to culture now. It can do the same for new art as well. I may not love this or that aspect of Miró, Dada, German Expressionism, "degenerate art," or some other past shock, but I can still see them as more more thrilling than Jeff Koons.

In The New York Times, in fact, Holland Cotter supplied just that act of imagination. He had a wonderful description of Miró's dissatisfaction with painting. He took pains to follow its twelve twists and turns along the way. Yet Cotter made the common mistake of operating entirely within the terms of the curators and the press release. He thus lifted the decade out of context in another way—the context of the avant-garde before it and the artist's recovery of painting after it.

A better review could offer a critique of what even someone as sane and knowledgeable as Cotter accepted. It could draw on a wider history and the methods of critical theory. And the exhibition could get more exciting that way. Critics I like most, from journalists to scholars, can take that route. If a Web site has the freedom to operate in the space between them, however, maybe that can make it worth your while.

This site is huge

With luck, too, that explains something personal: this site is huge (and growing). Not that it has the most readers of any art blog, although it has its share. I mean that it has more art. I have now reviewed at least two thousand artists and critics, in depth—with briefer notes on countless more.

While my tally is totally arbitrary, a thousand still felt like a landmark when I passed it on the 2010 Fourth of July weekend. I want you to feel that you have a place on the Web to which to turn, not just for opinions, but as resource. I search the site all the time to remind myself who artists are. (Yes, that is every bit as embarrassing an admission as it sounds.) Let me explain more about how I began, though. You will see why the numbers add up.

This site began in 1994, as the steadily expanding set of "static" Web pages that still forms its core. Eight years later I made the home page a blog. I use blog posts as teasers for the longer reviews, and I take them down after several months. The blog includes (at right) a free Google applet, which will search the site for anything. However, the design also has two-line listings for all articles, arranged alphabetically by artist or critic under discussion, so that you can browse. And the list of names, as you can see, is searchable as well.

This home-grown search engine can handle only last names. (I also index the names of selected group shows.) Still, I can now say that the javascript behind it contains more than a thousand names. Sure, articles mention many more. And many of those indexed names are the subject of several articles. Some artists, like it or not, will just not go away.

I always imagined this site as my personal space, a place to take time with art and ideas, beyond the word counts and puffery requirements of most magazines, but while reaching people who get their art news from friends, social media, or the papers rather than serious journals. And I want it to be a gateway to art for you as well. I try to add background, rather than parrot artspeak and "martspeak." I think that is what arts education should do—and too often fails to do. You can also browse by period in time, for links to the same names—and articles have thousands of links between one another, too. Articles end with links to a separate listing for galleries and museums, with hours and Web sites as up-to-date as possible.

The site has huge gaps, and it had them even before Covid-19 left me an art critic on lockdown. It is a one-person operation, reflecting the limits of my knowledge and tastes—and of what gets exhibited (although I do have book reviews and extended essays on broader themes). It also has the strengths and weaknesses of premeditation. I see a show early in a run, try not to write until I have thought it through, try not to write anything at all unless I have something to contribute, and then set most things aside before hitting publish. I surely would have more fans if I had made the site more impulsive, and I might have more self-respect if I had made it more scholarly in tone. But I like to think that meets a need.

A related review looks at what happens to critcism after the death of Peter Schjeldahl and retirement of Roberta Smith.