That Good a Year?

John Haberin New York City

Small Shows Think Big: 2022 in Review

For once, a top ten list looks tempting, even to me. Was it that good a year?

Not that 2022 had an earthshaker, a show that finally had to be. Nothing spanned two museums in two cities like Jasper Johns in 2021, and nothing so defined the last half century of art. But that is doubling satisfying, for someone who wants even the best shows to be more than a circus. I could even take pleasure in the dreaded New York art fairs for their near return to business as usual. I can still resolve to skip the fairs next year. We shall see!

Not that I am any less averse to picking winners. For me, a critic is more than a tastemaker—or maybe less. My tastes are not the point, and a trendy person like you can decide what to do with your weekend. My job is to tell stories that illuminate exhibitions—to get you intrigued about art that I myself may not always like. For 2022, the choices are many, and you need not count to ten. As always, you can follow the links to fuller reviews, and I hope you will.

The blockbusters delivered

The Met had to know it had a crowd pleaser in The Gulf Stream and Winslow Homer. If that sounds like loading the dice, it is not just on hand, in the Met's collection. It also brings out his commitment to light and landscape, as the centerpiece of a career survey. Even more, its gathering storm with a lone black man in a very small boat shows the Gulf as a warm but dangerous place. It exemplifies that great stain on the nation's history, its treatment of black America. For Homer, a sense of place is a sense of history.

The Whitney had to know what it had as well, with Edward Hopper. It does, though, go beyond greatest hits by rooting his art in New York City, where he lived, on the north side of Washington Square, and which he tirelessly explored. What, then, is New York, and what is a landmark? How does the urban scene ground or disturb the image of his art as the epitome of loneliness and light. Can it still transcend time and place? It is time someone asked.

Another view of the city has to work to draw crowds, just as the Jewish Museum did sixty years ago. As its director, Alan Solomon focused on contemporary art and took Robert Rauschenberg to the Venice Biennale, but he but he turned for art to a vital city. "New York: 1962–1964" opens with a photo mural of the Bowery and a juke box. It sets painting and sculpture amid urban renewal, dance, and poetry. Artists sought collaborators in politics and other arts, too. A gloriously cheesy girl with a radish by Marjorie Strider becomes breaking news.

Big shows can be small, too

The biggest crowd pleaser of all took just three rooms, for The Red Studio by Henri Matisse. And one of those rooms held only a video documenting its restoration. Another traced its history, in a collector who refused it, a fashionable men's club, and at last the Museum of Modern Art. The painting itself appears as Matisse would have seen it in a new, spacious, well-lit studio. In a curatorial tour de force, it also appears amid what became painting within the painting, as well as sculpture. He relished and altered past work, in his development as an artist.

Other shows got even less space and a lot less talk, but they should count as blockbusters, too. The Guggenheim displayed a single work by Eva Hesse, in all its monumental scale and faded materials. Hesse relied on both for her vulnerable and very personal reply to Minimalism. MoMA's misguided atrium made an impact, too, for once. Just six paintings by Susan Rothenberg and floor to ceiling text art by Barbara Kruger offered no escape. What did Rothenberg mean by her signature image, a horse, and Kruger by her aggressive politics? Small shows in an outsize room added up to at once retrospectives and monumental installations.

Big galleries could get in on the retrospective action as well. David Zwirner recreated a breakthrough show for Diane Arbus, tweaked its own earlier presentation of William Eggleston, and hung Joan Mitchell on a scale of up to four canvases across. The photographers looked more unsettling than ever, the painter more defining. All three have had major shows before, but Betty Woodman is well overdue for a massive display at David Kordansky. Her ceramics spill out across pedestals, walls, and floor—and pleasure pours out from her not so Grecian urns. As I write, Mitchell-Innes & Nash looks back at two decades of Martha Rosler as well, still feminist, comic, and angry, but also curiously at home around shopping bags and a dining-room table.

Acts of recovery

These turns to the recent past are acts of recovery. So, perhaps, is every exhibition worth doing—recovery of the willfully neglected past or the over-celebrated and underappreciated present. The art scene has made that an imperative as well, and it keeps paying off, especially but not solely with women. Vivian Browne, it turns out, found herself as an abstract artist on a trip to Africa. Younger black artists, too, are claiming at once their roots and their command of Western art. The Afro-Caribbean diaspora can run both ways.

Other Chelsea galleries found Michael West and Albert Kotin (the first a woman) among the first generation of postwar art and Lynne Drexler among the second. Is there more to the drive for diversity than a gallery's profits or a curator's career? The disdain for second-generation Abstract Expressionism had a point. So did the disdain for expressionism itself thirty years ago, at the height of political art, conceptual art, and critical theory. I still puzzle over how much to value decent enough painting now. Yet these concentrated bursts of color are worth remembering.

Other Chelsea galleries found Michael West and Albert Kotin (the first a woman) among the first generation of postwar art and Lynne Drexler among the second. Is there more to the drive for diversity than a gallery's profits or a curator's career? The disdain for second-generation Abstract Expressionism had a point. So did the disdain for expressionism itself thirty years ago, at the height of political art, conceptual art, and critical theory. I still puzzle over how much to value decent enough painting now. Yet these concentrated bursts of color are worth remembering.

Recovery can also mean not taking the obvious for granted, like Robert Colescott and, before him, Faith Ringgold at the New Museum. Is there no more to Colescott than one or two paintings, cheaply comic painting at that? His versions of The Potato Eaters and Washington Crossing the Delaware take Vincent van Gogh and American history where they refused to go—in a career that encompasses half a century of African American art and ends in mural-scale abstraction. Ringgold, in turn, embraces the darkness of black history and, as her titles have it, The American People, only slowly letting in the light. Will the bloodshed ever end? Only if others, too, pay close attention.

Domesticating destruction

Speaking of Afro-Caribbean movements, what about the Caribbean? If curators can use diversity and recovery as a form of self-congratulations, so did El Museo del Barrio with a co-founder, Raphael Montañez Ortiz. Now if only his art were not so stuck in place. His taking an axe to a piano meant to get attention—and it has, no matter how often he repeats it, which is plenty. "Destructivism" also meant to call attention to the devastation facing Puerto Rican Americans and their creative in its face, and his black relief sculpture comes close. As he struggled to move past it, though, he had little to show for it.

A follow-up posed a similar tale of devotion and collaboration with a Cuban American, Juan Francisco Elso. One might do better, though, to head across the hall for what the papers have missed, the quieter rebellion of Amalia Mesa-Bains and her circle, with what she termed "Domesticanx." A woman's work is not so easily undone. One might do better still to dwell on Puerto Rican art today at the Whitney. "Art After Hurricane Maria" may sound routine and the artists unfamiliar. Yet that allows them to speak for themselves and to one another.

It also sounds ever so politically correct, and its target is less a natural disaster abetted by climate change than the United States. Not that it pleads for statehood, which it pictures (wrongly, I think) as an excuse to profit off the island's real estate and tourism. It blends first-person accounts of loss with found imagery in new media and installations. They lend an elegiac tone and visual richness that tempers the anger and lingers in memory. The show ends with the side of a school bus, backed by the Puerto Rican flag in black and white. Here education is slow in coming and no one's flag hangs high.

Beyond the hype

Should you forget the blockbusters after all? As with alternatives to Ortiz, a good strategy might be to look beyond the hype and critical attention. When it comes to African American art, museums love Nick Cave and his colorful "sound suits," and the Guggenheim makes the case for their political subtext as well. Are they also glib and unduly accessible? Turn instead to Theaster Gates, with all three main display floors of the New Museum now that Ringgold and Colescott are gone. From video to painting and from pottery to billboards, his constant self-reinvention is a constant challenge.

The Met sure tries for a blockbuster, with Renaissance art in Tudor England, but that country's Renaissance was slow in coming. Gawk if you like at the dynasty, for which a display of wealth mattered as much as a display of Nicholas Hilliard and Hans Holbein. Or look back to Holbein's drawings at the Morgan Library. Even better were drawings by Jacques-Louis David. After speaking truth to power during the French Revolution, he spoke for power under Napoleon—and ended up in exile anyway, having alienated everyone. The Met asks how his Neoclassicism, his shifting politics, and the modern era came to be.

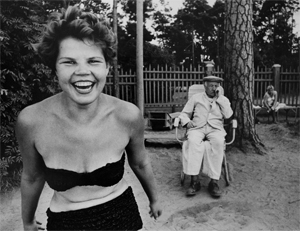

Wolfgang Tillmans is tailor-made for hype, and he got it, with dazzling press and the entire sixth floor at MoMA. He does, after all, keep experimenting and keep giving voice to queer themes. To my mind, he is also indiscriminate in his art and endlessly frustrating. For photography, one could go instead to the International Center of Photography, for Robert Capa and the poignancy of hope in the Spanish Civil War.  Documentary photography has never had so human a face. Just before his show, William Klein found the energy and urgency of a city wherever he went, from New York to Moscow and the "fight of the century."

Documentary photography has never had so human a face. Just before his show, William Klein found the energy and urgency of a city wherever he went, from New York to Moscow and the "fight of the century."

Whose best?

I could just as well have mentioned the Neo-Minimalism and natural light of Kapwani Kiwanga, a floor or two above Colescott, or Tiona Nekkia McClodden with a love for dance and a loaded gun. I could have mentioned other urban photography, from Ray Johnson with a disposable camera at the Morgan—or Jamel Shabazz at the Bronx Museum, on the streets of Harlem. So why not let someone else choose the best, like the Whitney? Not that anyone has called the Whitney Biennial the best or most representative contemporary art in years, and its very existence is harder and harder to justify. It still gets people talking and makes or breaks careers, but it can feel like a chore all the same. Yet this year's could top my personal best of 2022.

It does so by shifting again and again before one's eyes, as darkened, quiet rooms become all-encompassing and abstract art becomes installation. An open plan on one floor and enclaves on another provide two ways for different artists to collide and to thrive. Daniel Joseph Martinez speaks of "becoming post-human," but it might be better to say that the artists take stock of humanity and the city to ask just what is left. Color and gesture enter in due course, on both sides of a canvas, leaving one to determine what lies behind them. There have been more controversial and attention-getting biennials and triennials, and there will be older, younger, and greater artists. It is hard to imagine, though, a more creative setting.

In the end, the best will always be a recovery, and two last shows look farther from New York. The Met brings back Stone Bluff Manufactory in South Carolina, in and around the Civil War, long before Woodman or today's fashionable ceramics. They assert a black artist's signature through the wild expressions of "face jugs"—or inscriptions on large, deeply glazed, and finely polished stoneware. And the Morgan Library looks back father still, to Mesopotamia, where the written language began and women were among the first writers. They appear as creators and subjects, with a striking individuality amid ancient hierarchies. Go back far enough, and the best keeps getting better.

Of course, this site has reviewed pretty much all this and more at length. I did not review Joan Mitchell at David Zwirner through December 17, 2022, or Martha Rosler at Mitchell-Innes & Nash through January 21, 2023, because of past reviews. Other dates and locations appear with fuller reviews, with links here. You can now also see year-end reviews for 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2023.