A Listless Year?

John Haberin New York City

All Over the Map: 2012 Art in Review

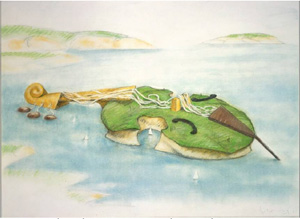

Tacita Dean Remembers

I do not want a "best of 2012" list for art. So much of the past year was business as usual, and the rest was not at all about the next big thing. It was about art that truly runs all over the map.

It runs from Manhattan to Bushwick and beyond. It runs from conceptual art and installations to painting and sculpture—all the while daring you to tell them apart. Instead of my ten best, then, my ten paragraphs wrapping up 2012 will try to run free as well. I would be remiss, though, if I neglected also to mention other losses in barely the last year. Tacita Dean makes them the focus of her videos of artists and critics. She pays tribute to Leo Steinberg, Merce Cunningham, and Cy Twombly, along with surviving artists at work in Claes Oldenburg and Julie Mehretu.

Blockbusters and a deeper history

This year even blockbusters brought only small pleasures. With Andy Warhol, Gertrude Stein and her brethren, Henri Matisse, or Picasso in black and white, museums delivered the obvious, apparently mistaking you for a tourist without Internet access to check up on them. Once one got over the greed and stupidity, though, the obvious looked rewarding enough.

Yet museums also explored neglected passages in art history, like the Renaissance portrait, Renaissance bronzes, an early Renaissance master, and Diego Rivera with Renaissance-style fresco. They cast Edouard Vuillard as Jew, the Caribbean as multicultural, George Bellows as a man of the people, and John Chamberlain as a Pop artist. They discovered postwar Japan, Mono-ha, and the lasting influence of Romare Bearden. All these stirred critical gushing and, a month later, renewed forgetting—but you and I could still look and learn. The Met somehow managed to turn clay models that Bernini himself preferred to destroy into a small retrospective. A bigger or more revealing one is not likely to come any time soon.

So-called minor media became major. One should know that by now about textiles and the decorative arts, after years of feminist criticism. Sharon Lockhart, Noa Eshkol, Rosemarie Trockel, and Al Loving, though, knew it all along.

Photography had a particularly strong year, with Joel Sternfeld, Francesca Woodman, Jill Freedman, Rineke Dijkstra, Paul Graham, Richard Misrach, Robert Adams, and Gordon Parks. Andrew Moore used the medium to recover not just Detroit and the Hudson River Valley, but other passages in art history, starting with Charles Sheeler.  Still, these were mostly not grand portraits of America, so much as the dark undercurrents of private imaginings. Charles Ritchie found much the same unfamiliarity and intimacy close to home in drawing.

Still, these were mostly not grand portraits of America, so much as the dark undercurrents of private imaginings. Charles Ritchie found much the same unfamiliarity and intimacy close to home in drawing.

Drawing in fact delivered what, to my mind, were blockbusters. Only works on paper could take New Yorkers to late Renaissance Florence, the age of Rembrandt, and a double dose of Michelangelo—the last as part of great museum collections that even European travelers might never see. Drawings could also recast late modern art. For Joseph Albers, Ellsworth Kelly, and Dan Flavin, dogma and Minimalism had their roots in landscape and light.

Expanding and surviving

The Drawing Center itself staged a comeback, although starting with painting. And it was just one museum renovation that, for once, deferred to curating—like the Barnes Foundation after a nine-mile journey and the Met's American wing. Best of all, the Yale University Art Gallery can now contain multitudes.

Loving was also a reminder that the art scene can, now and then, find new treasures in a generation not long past away. New York found room for Anne Truitt, Bill Bollinger, and Ralph Humphries (plus the strange demons of Jan Müller before them all). It found that haunting video reminder of others, too, thanks to Tacita Dean. Even better, the year paid attention to artists still at it, despite the clamor for younger rising stars—artists like Alfred Leslie, Judith Bernstein, Melvin Edwards and other "new black heavies," Thornton Dial, Sheila Hicks, Phyllida Barlow, Martha Rosler, Joshua Neustein, and Charles Hinman.

Hinman, for one, is alive and well, and so is abstract painting like his that takes major liberties with the picture plane—or, for that matter, the medium. The boundaries keep breaking down for sculpture and installation as well. Sensitivity to the everyday can mean much more than overblown piles of trash.  The Whitney had a double dose of Post-Minimalism, too, with Richard Artschwager and Wade Guyton, but they came off as mere boasting by comparison.

The Whitney had a double dose of Post-Minimalism, too, with Richard Artschwager and Wade Guyton, but they came off as mere boasting by comparison.

Maybe most of all, we survived. We survived Sandy—although Smack Mellon, Lombard-Freid and its neighbors, and an entire block on West 27th Street ended the year still closed. And the storm's full impact on struggling artists and dealers is surely still to come. Maybe better still, we survived the noise.

We survived ever more stages in the perpetual art fairs, including the advent of Frieze New York. We survived the big deals and ego trips of Tomás Saraceno, Tom Sachs, Alighiero Boetti, Yayoi Kusama, Gabriel Orozco, and (one can only hope) Jeffrey Deitch. All of them surely mattered a great deal to someone—but not, I think, to the day in, day out work of contemporary art. We hardly blinked at another Biennial and Triennial, which sounds disappointing until one looks back to the previous one. And the Studio Museum is again showing that emerging artists still matter, but galleries and studios show that every day.

One Brit, five Americans

Tacita Dean approaches new media as still life, as if even landscape and pixels had stepped outside of nature and time. She treats people the same way. She turns for portraits to the art world and to those she admires, to inspire the same reverence in others. And she admires them most at work—but in work that evolves slowly to the point of invisibly.  She treats them like objects, but they are looking, too, and often as not the camera adopts their point of view. How little can happen, she seems to say, when one is working hardest and cares the most.

She treats them like objects, but they are looking, too, and often as not the camera adopts their point of view. How little can happen, she seems to say, when one is working hardest and cares the most.

This has to sound ponderous, and it is. For her Booker Prize, Dean made nature itself in need of an artist's blessing, in black and white. Still, an enormous tree's beauty kept growing on me, and anyway the English are like that. Damien Hirst takes art as a matter of life and death, after all, even when he turns it into kitsch, and Francis Bacon would find physical desire lacking without existential despair. Now Dean encounters five other artists, along with a healthy American dose of reality, and the collision has a poignancy of its own. They may not accomplish much, but they care enough to stick to their work.

Much of the poignancy comes with the show now closed at year's end—from who and when they were. Leo Steinberg died just last year, and Dean stresses that the writer helped her understand Michelangelo in the isolation of late work. She also has to appreciate a critic who moved between contemporary art and art history, much as she wants to do in her art. Steinberg championed Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Philip Guston when it mattered, with the idea of the picture as a "flatbed" that helped define Rauschenberg's combine paintings for others. He gave her only a few hours, and she displays only photos of him writing. Otherwise she makes sixteen-millimeter films, forty of them now, in an obsession with the personal touch and the past.

Merce Cunningham gave her three days before his death in 2009, which she edits into the course of creativity and of a day. Running nearly two hours, Craneway Event captures his studio overlooking San Francisco's water and sky. Dancers rehearse together and improvise alone in Albert Kahn's 1930s factory, punctuated by inaudible talk, rhythmic clapping, encroaching darkness, Cunningham's wheelchair, and a single bird taking its rest.  Claes Oldenburg survives, but he lost his companion in sculpture, Coosje van Bruggen, in 2009 as well. He lingers over his Manhattan Mouse Museum, but few of its small, hard objects recall popular culture—and none is going to collapse like his toilet seat. He also dusts the shelves with a paintbrush.

Claes Oldenburg survives, but he lost his companion in sculpture, Coosje van Bruggen, in 2009 as well. He lingers over his Manhattan Mouse Museum, but few of its small, hard objects recall popular culture—and none is going to collapse like his toilet seat. He also dusts the shelves with a paintbrush.

Cy Twombly, too, died last year, and Dean shows him contemplating sculpture that often hides him in its shadows. She titles her half-hour Edwin Parker, Twombly's given name, and she traces his creativity to an anxious child. He remembers his mother asking, Does it make you happy now? (At times.) In five prints, Dean picks up Twombly's spare traces on gray while recreating her own student work in chalk. On film he emerges in sharp focus from behind a white mass, but slowly, and never with a glimpse of his painting.

This company must have Julie Mehretu scared for her life at barely forty. Dean gives her just four minutes, maybe so as not to claim to encompass a future. Mehretu at work moves between her PC, a worktable, and scaffolding, as she creates wall paintings with assistants. The small twin projections connect to her intense color and to scale of a monitor. They also run to different lengths, leaving them perpetually out of synch. Ponderous or beautiful, the eyes of the artist are multiply at stake.

Tacita Dean ran at the New Museum through July 1, 2012. Of course, this site has reviewed pretty much all this and more at length. You can now also see year-end reviews for 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023.