Channeling Romanticism

John Haberin New York City

Crossing the Channel: Britain and France

Manet and the American Civil War

Maybe everyone has had this dream. I have had it. Probably you have, too. So, apparently, has the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Consider two exhibitions—of Romanticism and Manet crossing the Channel.

You decide

Freud himself describes it. Sherrie Levine has parodied it. There you are, in the lecture hall, with that horrible old desk, like a chair on steroids. The exam sits in front of you, for a course that you neglected to attend and a text that you never managed to finish.  Or midnight has long passed, and you have not so much as thought about the paper due that very morning.

Or midnight has long passed, and you have not so much as thought about the paper due that very morning.

Okay, get a hold of yourself. This course covers the 1820s. I want to know, now: define Romanticism. You can no longer bear the anxiety. You grope for the pencil, write one line, and rush out of the room as fast as you can. "It is what all those artists did in 1825."

Do not despair. You may fail the course, but you could find a job curating at the Met. Its show of British and French painting comes up with the same answer. It makes for a boring visit, and it takes away from some great paintings. It does, however, get one thinking about such hoary ideas as quality and tradition. Could the museum alone really create them or cast them aside?

The exhibition definitely means to question art history. Textbooks trace French art from Classicism to Romanticism, with a few borderline cases along the way, then on to Realism and Impressionism. They take John Constable to the English countryside and J. M. W. Turner to Venice, before the Victorian nude puts British Romanticism to rest. The Met brings France and England together, as mutual influences.

Textbooks also outline styles, personality, politics, and progress. The Met's big second room throws up anything that the academies could have exhibited around 1825. Portraiture and genre painting hang near landscape and history. The creators of a movement hang beside artists fashionable with the aristocracy. Which really mattered, who contributed what, and why? You decide.

It may sound more like a book than an exhibition, and as usual the Met has tendentious labels next to each work, boasting of its significance. Painting itself blends into reproduction. Théodore Géricault took Paris by storm, so to speak, with his epic painting of disaster at sea—The Raft of the Medusa. A contemporary copy, all 15 x 21 feet of it, covers every inch of the entry wall. I mistook it for the usual oversize entrance photograph that gives proper dignity to museum blockbusters. Again art history may serve up reality or institutional power, and only you can decide, if you care—or if you dare.

A year in the life

The Met actually has a point. For one thing, a couple of landmarks changed art. One, or at least that reasonable facsimile of one, stares out by the entrance. I could see why Géricault felt the urge to rent a studio large enough to complete it.

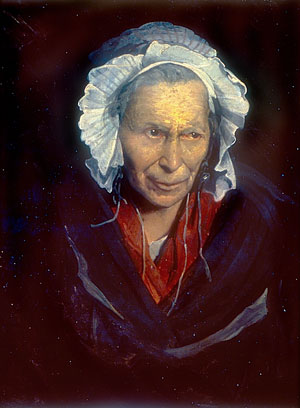

Its intense color, sweeping gestures, unflinching eye before physical and mental suffering, and identification of humanity with something larger than any man or woman—all of this ushered in Romanticism. His huge canvas combines a heroic scale and equally heroic poses with a thorough disdain for heroics. Their grand pyramid points to salvation high on the horizon. Yet the survivors of the wreck shocked France with tales of cannibalism. The Louvre cannot lend the original, but the copy does not look half bad. A small first room further explores Géricault's studies of severed limbs and lunatics.

For the second landmark, the Met means something even more political. After the Battle of Waterloo, art and artists could cross the Channel. The French could see more freely painted and closely observed landscapes, such as Richard Bonnington's pale skies, Turner's drenching sun, and Constable's lucid clouds and trees. With Turner's epics, they could also see Edmund Burke's sublime in action. In turn, the English could see exotic narratives, of monks at prayer and Arabs at war—including medieval scenes that the French, in turn, borrowed from Walter Scott. From Géricault, Eugène Delacroix, and Delacroix drawings, England also got to taste unsentimental drawing and color.

The Met has a point about art history, too. Postmodern critics have slammed the idea of art as the onward march of great men. Feminists, among others, have every right to ask who gets left out. Historicists can refuse to see key artists apart from a wider culture shared. Anyone visiting the Met might wonder at how past politics—or present museum institutions and donors—shape what one sees today.

The Met long ago rehung its nineteenth-century wing, so that the entrance hall subjects one first to academic painting. The Museum of Modern Art showed early modern artists still "Making Choices," before they found their way past inherited clichés. The Guggenheim gave me the best chance of all to ponder these issues. It dredged up unfashionable work by obscure and famous artists alike, to picture early Modernism as "Art at the Crossroads." The Met simply takes the story back half another century.

The Met also responds to criticism of these exhibitions. Did other surveys create a false idea of their time, featuring work that few could have seen even in its own time? Did they go out of their way to make good artists look bad? The Met claims the trappings of objectivity and even quality. After all, it picks from actual Salon and Royal Academy exhibitions, not just studios, and it sticks to a quantifiable benchmark—the year 1825, plus or minus a small error bar. It may not look much like the art history I learned, but it could pass for fancy statistical surveys in social science.

One big happy family

Once more, this is starting to sound like a terrific book, but it adds up to a depressing exhibition. Like earlier revisionism, it tries to shake the cobwebs off familiar art. Like much revisionism, too, it deadens the experience of groundbreaking artists. Almost as bad, it leaves one unable to make sense of the rest. Worse, it actually hides the museum's role in all of this.

Some of the problem comes with any survey at once so sweeping and so narrow. With so many unfamiliar artists, one hardly knows who did what when. Conversely, artists did not have to paint their best or most representative work just because the calendar read 1825. Géricault and, before him, Baron Gros had been nurturing a new kind of drama for some years then, and older styles hung on for a long time after, as did a nostalgia for Napoleon. The museum, for its part, offers no help in sorting things out. Everything looks just fine, thank you, and everyone, it insists, influenced everyone else.

The problem runs deeper, however. When a major museum tackles museum politics, it had better lay its cards on the table. The show asks one to question authority. At the same time, it neglects to say just who is running the show. Sure, some answers fall to the viewer, but only after the curators design the multiple choice. Sure, the date supplies a veneer of objectivity, but every time works hang side by side, they necessarily plead a case.

For all its postmodern veneer, the show shills for the establishment. I mean not just the subordination of innovative artists to the academies. I mean the picture of Romanticism as one big happy family. Do some curators flatter bourgeois individualism, with a great-man theory of history? Here the aura of artistic genius gives way to another pretense, one perfect for holiday presents and public television. It boasts of an age without internal divisions, the art world as the Family of Man.

One spots the museum's hidden agenda in the juxtapositions. Artists formed a generation years apart hang next to one another. David Wilkie paints glossy, sentimental narratives of small-town English life, while Delacroix briskly sketches violence in colonial lands. The Met sees only a shared interest in genre. Camille Corot found a crisp yellow light in Rome, but the Met detects only the influence of Bonnington, whom he may never have studied. Late Corot frees paint from individual trees, but the Met cannot tell his dense weave from Paul Huet's academic precision.

The Met lumps together France and England, artists from before the Revolution with the children of Romanticism. It suggests a world without national rivalries, artistic rebellion, or class struggles. In other words, its leisurely view of the past reflects the complacent assumptions of the museum and media establishment today. Actually recovering Romanticism, with its active engagement between the human mind and nature, might upset things a little too much. Definitions, Wittgenstein argued, turn on family resemblances—but all happy families are not alike.

Channel firing

Only this summer, the Met took a step toward the Channel. It took as its subject the early 1860s and Edouard Manet, who knew the Channel well. In fact, he later painted The Departure of the Folkestone Ferry. Yet this show, too, backed off exactly when the questions got tough. It, too, introduced a French artist as a man of the world, and it, too, shied away the moment his world involved nations at war and art movements in collision. Paradoxically, it thus failed to see an artist's ambivalent approach to the same things, a daring hint of Modernism still in the making.

During the American Civil War, a sea battle took place off all but within eyeshot of the French coast. Manet quickly portrayed the event, with the urgency of journalism or politics itself, much as he addressed global politics in his Execution of Maximilian. The Met assembled the paintings and the evidence. A small show often does more than a blockbuster to bring art alive. It can focus on the overlooked. It can give art context—or give it a chance to breath. I expected no less.

The Met leaves tantalizing clues. Before turning to the Salon, Edouard Manet wanted to go to sea. The Met mentions that major career setback, but only to let it drop. Was Edouard Manet reliving a dream of his youth? If so, did his failure oblige him to represent it indirectly, through American rather than French fleets? How often did he turn to seascapes? What, indeed, happens when one returns to the sea not as a boy's ideal of a sailor, but as an adult versed in fashionable resorts? The Met would not say.

Manet, the show noted, chose a diagonal composition and a high horizon, with one ship at a distance. He was invoking Géricault. Did he thus take the American victors as freedom fighters or as akin to cannibals? His broad, green expanse, all but filling the canvas, in turn led to paintings by Claude Monet, Monet in Venice, and James McNeill Whistler. Like Manet, they found yet another model for great waves, through the influence of Asian art. How, however, does one get from the birth of Romanticism to Japan? Again, the Met has a few photographs of the time, but nothing that suggests thought about the art itself.

More important, why the Civil War? Did the French enjoy the Union victory as a tweak at America's old enemy, the British? Did artistic rebels identify with the cause of rebellion—or with opposition to slavery as an affront against the "rights of man"? Or did they just enjoy the spectacle handed to them off the coast, like Manet's bullfighters? The Met comes up with a scale model of the Union vessel, but not a single press clipping about the war or a single document for Manet's own identification. How quaint, and how far from the politics of art and history.

Manet turned to the Romantics, including Francisco de Goya and now Géricault, in the 1860s, as his art was shifting from Renaissance models to what Charles Baudelaire famously called the "painting of everyday life." He was drawing closer to his own political, sexual, and social world—and the viewer's as well—here as a man of the sea, later as the adept in café society. And here, as later with A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, the closer he and the viewer get, the more the painterly world forbids access. The sea looms up like a blank but ever-shifting slate, anticipating the barmaid's uncertain expression and the mirror behind her. The object of one's gaze, like the ship on the horizon or the legs of a trapeze artist later, almost slip out of the canvas. Politics, self, art, and certainty press in from all sides, with dangerously beautiful and unstable results.

Quality and quantity

The Met borrows postmodern rhetoric in order to bury Postmodernism's most vital criticism. It may set aside older definitions of Romanticism. However, by putting quality and interpretation on the back burner, it leaves intact a complacent view of art. It leaves one with the illusion that art has a purity unsullied by human judgment. No wonder it leaves the museum above reproach.

Traditionalists know art when they see it, and they know good art as well. They mistrust departures from the canon as "anything goes." Once anything can be art, they reason, anything belongs in museums. Once objective criteria for art vanish, so do values. Yet one could argue the opposite. Once dead cows and upturned urinals pass as art, viewers have more choices, and a buyer's market means tougher customers. Call it the free-market theory of value. Instead of "anything goes," speak of deregulation.

If that sounds silly, it is. Still, think of an afternoon in New York's Chelsea or in London today. Far too often, I try to see so much that I pay enough attention only to what I know right away I shall like. You can see why I have called Postmodernism merely Modernism pressed for time. Even in a less cynical world, however, something becomes art by virtue of its claim on one's attention.

A dead cow or a urinal cannot appeal to criteria based on virtuosity, media, or authenticity. It can only insist that it matters. It can ask one to confront one's own nature and the nature of art. It can take pleasure in that very word nature—or turn on it as well. In short, it becomes art by invoking the need simultaneously for judgment and interpretation. They become empty without each other.

One can still dismiss the object's claims, in which case one calls it bad art. Art reviews do that all too readily. A little more patience, description, and interpretation would expand the reader's frame of reference and allow the reader to judge. It would open others not just to shock art of the present, but to unfamiliar moments in the past. Either way, however, the work keeps asserting its claim. Value, definition, and interpretation always sneak back in, because they belong together all along.

When the Met postpones a definition of Romanticism, it pretends to go right to the facts. It pretends to raw experience, apart from tired interpretations and worn judgments. In reality, it substitutes a conservative, pre-Romantic vision, along with an overload of kitsch. It will take a more active imagination to locate the past and to see through institutional constraints. The effort might even make English and French Romanticism halfway interesting.

"Crossing the Channel: British and French Painting in the Age of Romanticism" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 4, 2004. "Manet and the American Civil War: The Battle of the U.S.S. Kearsage and the C.S.S. Alabama" ran through August 17.