Guilty Pleasures

John Haberin New York City

Gallery-Going: Fall 2003

At the very least, critics should feel guilty. When it comes to art, we pretend to authority, when we cannot possibly know it all.

We cannot remember it all. We cannot understand it all. We cannot even find half of it.

Maybe that explains why I took a special liking this fall to some shows without a lot of buzz. In different ways, they made the experience of art as fragile and guilty as, perhaps, it really is. Consider the latest not just from such stalwarts as Janine Antoni, but also from Matthew Geller, Peter Sarkisian, Kevin Hanley, David Shapiro, Amy Bennett, and some other stops along my blatantly arbitrary gallery tour.

Serious stuff

Not that galleries lack for terribly serious art. Julian Schnabel always takes art seriously, if only to acknowledge that his outrageous gestures may fall apart like shattered dishware. This time, he seems to have mistaken himself for a cross between Earth's most ancient civilization and Francesco Clemente or Sandro Chia. The totemic wood sculpture and large figurative paintings stand so far above irony as if to crush it. Ironically, Rolled and Forged by Richard Serra was running elsewhere at much the same time.

For those preferring know-it-alls of a decade or so later, Richard Prince gives up the Marlboro Man for stereotypes about nurses. The shift from appropriated photographs to plain old painting makes the message painfully obvious.

Terribly serious, however, need not mean terrible. It may even give some heavyweights an uncanny lightness. Mark di Suvero has long worked in the tradition of David Smith, bringing to industrial-strength materials the scale of Abstract Expressionism. Now one piece, even more open than his sculpture on Governors Island or at Storm King, turns at the slightest touch. An even larger sculpture by di Suvero gains in structure and openness from the airy symmetry of Paula Cooper's tall, gabled back room.

Matthew Geller also wants art larger than life, and not just because he takes over a whole city street. His Foggy Day invites one into the movies. Hollywood had used the same technique to fog up that very block, just off Chinatown. Now invited guests and casual strollers alike join in a spectacle without a beginning, an end, or a script. They end up staring at one another, at once actors, characters, and moviegoers.

At lunch the spray from above has all the novelty for Manhattan of a broken steampipe. Geller's sponsor, Creative Capital, argues that it brings out an old block's architectural features. One could praise it instead for hiding them. I have already forgotten why Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the architects of New York's High Line and High Line extension, have similarly blurred the entrance to a building in Switzerland. Maybe artists and critics these days are lost in the same fog.

As twilight falls, however, and people enter the mist shot through with strong light, they take on real glamour. Does Geller mean that ordinary life deserves every bit the aura of a film? Does he mean that personal identity exists as a fiction created by others, some with a big budget? Does he just like how it all looks? He could use a lot more content and less eagerness to please, but I could not fully shake off the mist or the vision.

Morbid fascinations

I appreciated some quite somber art as well. Jerzy Kubins, for one, paints in broad, thin streaks over wrapping tape. He combines the transparency of oil with the gritty, industrial texture of his Williamsburg surroundings. Think of him as updating American abstraction for Brooklyn real-estate values. Back in Manhattan, Lee Krasner in her final decades has a crisp beauty unlike both her patient wrestling with Jackson Pollock's art. A month later, her gallery offers Christopher Wilmarth's even more tasteful sculptures of metal and glass.

Still, I shall remember longer some exhibitions that make both art and viewer seem as fragile as judgment or a human life. Maybe good art has to feel that way. Art may hold out the promise of truth—to the artist's intentions, to the depicted subject, to the beauty of the work, to its objective existence, or to the viewer's perceptions. Yet it lives on borderlines between all of these.

Certainly Peter Sarkisian has one stumbling in the dark. As in his previous work at I-20 and at the Whitney, one struggles to make out ghostly presences, oneself included. One circles a wide, cylindrical screen as a man, flinging a heavy board like a futile threat, flashes on and off. Sometimes he splits in two to loud pops, and the asynchronous forms disappear as quickly as they came. Sarkisian means the circle and disjunctions, like the path of an electron, to evoke quantum mechanical uncertainty. I tried to forget the leaden metaphor and to appreciate the uncertainty of one's all-too-slow progress and all-too-rapid perceptions.

In another projection, small, round screens appear as openings onto deep wells. Figures vanish into the impenetrable white liquid or float treacherously above it. Elsewhere one gropes one's way into a dark room, pierced only by a small table, a glass of water, an elusive, shifting spotlight, and steady footsteps. Has one intruded on another's bedroom at night, an insomniac's restless exhaustion, or the loneliness of a small hotel? Has the other threatened instead to disturb one's own privacy, one's safety, and one's rest? Or is that other oneself?

The month before at the same gallery, Kevin Hanley also trapped one by the slow pace of perception. His video looks at first like a reasonably pleasant abstraction. As its colors come into focus, however, they gain a harsh clarity. They show a man's head, maybe Fidel Castro's, asleep or dead. If the association of viewing art with morbid fascination recalls Damien Hirst, so does a work a few doors down the street. Alison Hiltner's vending machine, unlike most art, serves up some real brains—along with a few less purely esthetic body parts.

The way we live now

If all this concern for mortality sounds symptomatic, so should the contrast with Hirst. A Britpack star knows that the London art establishment matters—so much that it turns life into death. The Americans see art and artifice as works in progress. Where Hirst sees life and death in the tony environment of art, they see people caught between solitude and pop culture. Where Hirst sees the artist as part of a dangerous circle, they see a viewer's guilty pleasures. Think of Sarkisian's film noir hotel room, Hanley's reference to fame in a political world, and Hiltner's office or high-school cafeteria.

New Yorkers probably have a knack for guilt anyway, especially when they hear it from their mother. David Shapiro sure does. He turns a gallery into a supermarket. If its aisles look obsessively neat, wait till one sees what fills the shelves. Shapiro has lined up two year's worth of empty bags and tins. Above it all, one hears him lamenting a compulsion to finish everything on his plate, what with all those children starving abroad.

New Yorkers probably have a knack for guilt anyway, especially when they hear it from their mother. David Shapiro sure does. He turns a gallery into a supermarket. If its aisles look obsessively neat, wait till one sees what fills the shelves. Shapiro has lined up two year's worth of empty bags and tins. Above it all, one hears him lamenting a compulsion to finish everything on his plate, what with all those children starving abroad.

At first, one smiles at the pristine completeness. Closer, one shies away from the harsh, metal edges and scraps of garbage. Then one laughs at the soundtrack, but only to share its guilt. Could he be right? At least he shares responsibility for the overconsumption with his cat.

Amy Bennett, too, links the pleasures of art with obsession, neatness, and an American lifestyle. She even calls one painting, like Anthony Trollope's Victorian masterpiece, The Way We Live Now.

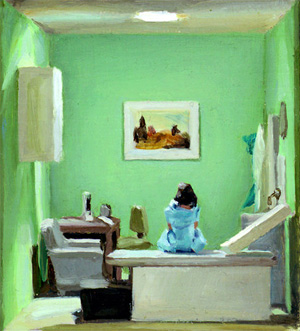

Bennett portrays suburbia in intimate detail, as if through an orbiting spy camera. She paints tract houses with the roof off. From above, the pattern of rooms and driveways takes on geometric precision. The idealized vision heightens the aura of late Modernism, as if everyone had maid service these days. At the same time, the trivial settings and idle pursuits turn Pop Art's flash and Eric Fischl's suburban irony into something plainer. The viewer's voyeurism becomes an act of self-exposure and appreciation.

Falling down on the job

Other shows, too, left me smiling at things that struggle to hold together. E. E. Smith did, by juxtaposing images and text. A month before and at the same gallery, Macyn Bolt also joined disparate panels and modes of expression. They set patterns side by side, sometimes abstracted from cobblestones or other common objects. They suggest abstract painting as subject to an inherited vocabulary and, conversely, as a work in progress.

More humorously, Jean Tinguely and his mechanized witches, like the busty women by his wife, Niki de Saint Phalle, have less of Macbeth than of trick or treating. They stand about the size of small children, and they wiggle as if they hardly know whether to beg for candy or just for attention. They do not self-destruct, perhaps, like the French artist's best-known installation. Tinguely himself died in 1985. They do seem unlikely, however, to outlast the artist all that much longer.

Have I been descending to sillier and sillier installations over the course of a review? With Janine Antoni, an appeal to myth and technology also falls apart, and she happily falls to the ground along the way. Two industrial drums, the kind that hold cable for construction sites, dominate the room. Rope wraps around each drum, and a single strand connects them, imagery and materials that remind me as well of Jessica Stockholder. The rope's other end unwinds across the gallery floor. There it spills out into loose fiber, like a bed of fine, blond hair.

Does this add up, and does it have to add up? I may never know for sure what Rapunzel's gesture of hope, the artist's gender, and the heavy-duty contraption have to do with each other. Yet I like imagining her and the work caught between stereotypes—of male and female, of fancy art and New York streets, of submission to the industrial revolution and to a woman's traditional craft, of an artist's tumbling and delicate balance. At the opening, she further personalized the work's boldness and fragility, taking them to a kind of illogical conclusion. She walked the single strand like a tightrope, tottering, moving ahead with ease, and finally collapsing on the bed of hair. I wish that I had seen its moment of clarity and humanity.

False positives

She makes me want to take back my opening. I do not pretend to authority, or at least I cannot until a few more museums put me on their press lists. Most well-known critics do not either. It only seems that way from their enthusiasm. Pardon me more ponderous sociology of art while I explain.

Art today, this Web site keeps insisting, turns on the past, criticizes it, and sustains it. It also rushes through the present. With so many blockbusters and so many galleries, even on the fringes of urban ideas and renewal, I keep saying, one can call Postmodernism just Modernism pressed for time. Too often, one can only look fast, push past, and move on.

The pressure can favor art that grabs attention, with familiar styles or shocking gestures. It can favor criticism that boasts of the latest, definitive trend. It costs a lot of money to sustain a gallery, and few artists get a fair chance. Still, I think that in the past I have erred toward one side of the story. The art world, like the alleged free market, is powerful but also a fiction. When one has instead too few choices—as with radio or the movies—then one really gets institutionalized museum blockbusters.

Art does better even than college radio, with a diversity that could never get commercial airplay. In music, without a healthy turnover between insiders and outsiders, quality stays pretty high, but the genres stay pretty static. It truly is only rock and roll. In contrast, art pops up all over town, even in New York's darkest alleys, for anyone to see.

Even that sense of hope, however, props up institutional clichés. It breeds cheerleading in place of criticism. In part, critics make more of a career move with outrageously good (or bad) reviews. In part, magazines prefer glossy, upbeat articles as the background for soliciting gallery ads, just as gallery hand-outs need a kind of "martspeak" to reassure buyers. In part, too, critics feel the obligation to describe, to explain, and to teach. They know that art takes words, that the public finds contemporary art scary and art's history remote, and that a bad review can mean only that one has missed the point.

In part, however, one simply feels glad to have found something worth mentioning. One cannot cover it all, and I certainly have not, so why not point to things that matter? The problem is that praise leaves the illusion once again of a stable art world, filled with unchallengeable art. Here I go, too, with this fall's tour of some highly selective gallery visits. Maybe it compensates a bit, then, if I have given space this fall to some less infamous exhibitions. Maybe, too, it will help if I just let this review now fall apart and go silent.

The work of Julian Schnabel ran at PaceWildenstein through November 15, Richard Prince at Barbara Gladstone through October 25, Mark di Suvero at Paula Cooper through November 15, Matthew Geller on Cortlandt Alley through November 14, Jerzy Kubins at Fish Tank through November 2, Lee Krasner at Robert Miller through October 11, Christopher Wilmarth at Robert Miller through November 15, Peter Sarkisian at I-20 through November 20, Kevin Hanley at I-20 through October 18, Alison Hiltner in a group show at Spike through November 1, David Shapiro at Jack the Pelican in collaboration with eyewash through November 16, Amy Bennett at the New York Academy of Art through September 13, Macyn Bolt at Kim Foster through October 11, Jean Tinguely at van de Weghe through September 27, and Janine Antoni at Luhring Augustine through October 25. A later review takes Amy Bennett outdoors.