The Real New York School

John Haberin New York City

Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis

If there was a New York School, Lee Krasner was the consummate New Yorker. She was born here, outside the Manhattan elites, and went to school here. Yet she learned at least as much from the Museum of Modern Art, founded in 1929, as she entered her twenties, as from the best teachers. For her, too, coming from an immigrant community to a growing circle of artists never meant leaving her roots behind. It meant working toward larger, more all-over compositions, in which line whips through paint and color.

One could say much the same about Norman Lewis, and the Jewish Museum makes the most of their pairing. Think about it—the daughter of Russian Jews and the son of African Americans from Bermuda, one from Brooklyn and one from Harlem, born just one year apart, amid all those hard-drinking white males. How close, though, are the parallels, in a show of just three dozen works, and how representative of their art is its focus, the years from 1945 to 1952?  Did they even meet? Together in "From the Margins," they also raise serious questions about an art movement, its origins, and who its histories so often leave behind. As a postscript, a gallery allows Norman Lewis to emerge from the margins.

Did they even meet? Together in "From the Margins," they also raise serious questions about an art movement, its origins, and who its histories so often leave behind. As a postscript, a gallery allows Norman Lewis to emerge from the margins.

Hebrew and jazz

Lee Krasner will always be part of the fabric of my city. I associate her work with its gorgeous tapestry of light brown and with the smell of a hair salon in the Fuller Building, where she had a gallery at her death in 1983, when I was just learning about modern. I look forward to her mosaic on State Street every time I leave the Staten Island or Governors Island ferry. She married Jackson Pollock a few blocks south of the Empire State Building, where I pass nearly every day. She introduced him to Hans Hofmann at the Art Students League, as close as the unruly westerner and student of Thomas Hart Benton ever came to a mentor. Without Hofmann, neither might have found an escape from an American Surrealism, toward an Abstract Expressionist New York.

Norman Lewis has his claim to the city, too, but museums have been slower to notice. Lee Krasner had her education at both its radical and old-fashioned places, at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design. She and Pollock spent much of their time on eastern Long Island, then apart from the wealth of the Hamptons. Lewis was nurtured on a sail through the Caribbean, after which he remained in Harlem. She had a full retrospective in 2001, at the Brooklyn Museum. He turns up when someone remembers to ask about black abstraction.

Yet he more than holds his own, in part because he got where he was going sooner. He loved jazz as he loved Harlem, and its characters and rhythms appear everywhere in his art. One can make out performers, instruments, and maybe even a musical score or two. All Lewis had to do was to let them loosen him up. One can watch his jagged line, most often in white, sinking more and more into larger and more luminous fields. Krasner works at every stage with exquisite care, even when piling on the paint. Perhaps inspired by what she knew of Hebrew letters, she assembles thin impasto brushstrokes into a tight grid of triangles and squares.

They could hardly be more different, in temperament as well as art. The show opens with photographs and two self-portraits. Born in 1908, she stands at her easel in 1930, in a crowded landscape of flowers and trees. Born in 1909, he painted just his head ten years later, with those color fields running every which way. She is her bright, stubborn self, asserting her calling. He is dapper and charming. She could have done well to forget a certain charismatic drunk and cheater to take up with him.

The show keeps looking for parallels, and it gets them, but more in their education than in their artistry. Already in her portrait, Krasner is determinedly high culture, but a European culture that Europe itself had pretty much left behind. She is still reworking Post-Impressionism as it made its way through its narrower spaces to Modernism. Lewis is blending high and low culture in both subject and style. A second room makes the case for their shared encounter with Henri Matisse and Cubism, and it did them both a world of good. The encounter took too long for all of American Modernism.

She adopts a style close to Stuart Davis, in work for the murals division of the Works Progress Administration. He adopts near monochrome rectangles, almost like Notre Dame for Matisse. Mostly, though, she is struggling, while he is jazzing things up. The musicians are more legible, and their field of color more compact, but otherwise he is on his way. And then in the third and largest room, they settle down. That room covers just the years from 1946 to 1950, so crucial to both artists—and to postwar American art.

Writing from the margins

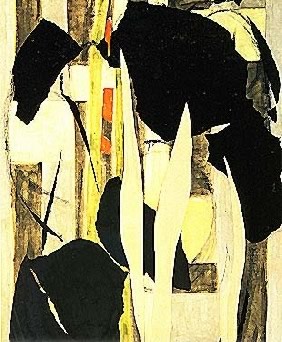

She may even leave him behind. He first concentrates his existing compositions into almost a dark cloud. She starts her Little series, that grid of geometry reaching to the edges, in black, white, and hints of color. He broadens his fields again, now more luminous than ever. With that growing and glowing cloud, anticipating Mark Rothko, he demands inclusion at last in a better history. Still, he is composing well within the borders of the canvas. She is working the entire picture plane into depth.

Krasner had the advantage of a sneak peek at Pollock, who had started drip paintings. She has two as well, one here and one in the show's final room, which carries her and Lewis into the 1960s. She is still fussy and obsessive. Her woven tracery pops off the canvas, less like Pollock than Janet Sobel, who has claims both to inventing drip painting and to outsider art. Still, Krasner's pop like nothing else in the show. If postwar art is about the art object, and if it is about color as line and line as color, she deserves more space in mainstream histories, too.

The last room leaps ahead to just a few works, as if to bid its actors goodbye. She has the largest, with only a few broad brushstrokes against a slightly lighter field, like calligraphic Chinese art, but in monochrome. He has the show's brightest work, with something like lettering spewing out toward the right of a bright, bold red. It takes the shape of a megaphone, because it is a protest concerning civil rights. Still, it is also illegible, and that raises the question of identity. Is this really about a man and a women, a black and a Jew—and what are they even doing in the same rooms?

Maybe not all that much. One could give them separate rooms, with little loss other than making obvious the paucity of the display. Both Krasner and Lewis deserve more, much more—and the curators, Norman L. Kleeblatt and Stephen Brown, have a long way to go to explain why Lewis is in the Jewish Museum in the first place. One must find one's own answers, along with the pleasures. Mine might begin with their shared line, so wiry as to become not just drawing but writing, whether in musical notation, in Hebrew, or in abstract art. It might include their shared preference for detail rather than the iconic form of Pollock's drips, Rothko's clouds, women for Willem de Kooning, cryptic block letters for Franz Kline, or canyons for Clyfford Still.

An explanation might also need to confront the politics of postwar American art. For supporters, Abstract Expressionism necessarily means the triumph of American painting. For detractors, it is and was a tool of American propaganda, centered on a white male drifter from the American West. At the very least, Krasner and Lewis elude those descriptions, as people and as artists. They should also have one remembering the actual politics and the players, without the myths. If they were children of immigrants, so was the movement.

Willem de Kooning came from the Netherlands, Hofmann from Germany, Arshile Gorky from displacement and genocide in Armenia. Robert Motherwell came to painting from the front in World War II and Ad Reinhardt, another child of immigrants, from the home front in the struggle against capitalism and fascism. Barnett Newman was a Jew. Maybe another look at New Yorkers in the New York School will include him. Meanwhile, one can grapple with artists that elude the terms of politics or complicity. Krasner and Lewis may or may not have another message in their text, from the margins of New York.

A postscript: into the light

Slowly but surely, Norman Lewis worked his way out of a kind of Abstract Impressionism, and museums even now are just catching up. The Jewish Museum paired him with Krasner to little point other than to demand attention for painters that too many have overlooked. It also covered just seven years, up to 1952, when both were reaching their peak.  It showed their transition from an earlier Modernism and representation. And it called for a celebration that was yet to begin—perhaps the 2016 Lewis retrospective at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. For now at least, it will take a Chelsea gallery to invite New Yorkers to join in.

It showed their transition from an earlier Modernism and representation. And it called for a celebration that was yet to begin—perhaps the 2016 Lewis retrospective at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. For now at least, it will take a Chelsea gallery to invite New Yorkers to join in.

Actually, the Jewish Museum did have a point or two, if also only a small exhibition. It saw blacks and women in postwar abstraction alike as, in the words of the 2014 show's title, still coming in "From the Margins." That meant both their reputation today and, in those seven years, the course of their art. It also singled them out as native New Yorkers, and the gallery opens with Street Musicians. It has more than a hint of both Pablo Picasso with his harlequins and Harlem streets. As a jazz aficionado and sophisticated artist, Lewis knew both.

It is also thoroughly abstract, and he painted it in 1948, when he left representation behind. While the show runs almost to his death in 1979, at age seventy, it is mostly about just ten years. If the Jewish Museum was about two painters finding themselves, here Lewis in his forties is finding something greater. The gallery, which surveyed Alma Thomas just before and about as well as the Studio Museum in Harlem, is up for the challenge. It starts before 1950, when he ran to vibrant detail, only to move on. At first, bundles of short vertical marks in color emerge from a brushy ground. One might indeed call it Abstract Impressionism.

Elaine de Kooning coined the term, but it caught on for others entirely, such as Milton Resnick and, especially, Philip Guston. When Lewis takes light blue or violet for his background, as with Street Musicians, he comes close indeed to early Guston, although critics then were looking the other way. Guston, though, was happy to set the sunlight, mist, and gesture behind him for sardonic self-representation. And Lewis was already darkening and deepening. Some of those first backgrounds were close to black.

They bring him out of Impressionism's daylight, as with Twilight in 1956. Even here, though, the brushwork is tightening and the central image merging with the black. If anything, it is also growing more luminous, like the city under streetlights late into the night. The colors glow as if from within the darkness, as for Ad Reinhardt—although without Reinhardt's dare to see anything but a black painting. They also suggest a greater depth, coiling across a canvas in later years like ocean waves. The draftsman is finally painting.

The gallery also catches him drawing, especially early on. Ink moves coils against white space, a style that he had used before for actual musicians. The abstract drawings, though, are leaner, with thinner dabs of ink coming off the coils at many points along the way. They could almost depict barbed wire—the materials for another African American, Melvin Edwards, in a show at the Brooklyn Museum on the theme of black power. Lewis, though, has little interest in anger or threats. He is growing darker solely to find his way into the light.

Lee Krasner and Norman Lewis ran at the Jewish Museum through February 1, 2015, and Lewis at Michael Rosenfeld through January 26, 2019. Related reviews look at a retrospective of Lee Krasner, Krasner in collage, and blacks and women in postwar abstraction.