Flyover Country

John Haberin New York City

Donna Dennis and Greg Lindquist

Aspen Mays and Sam Falls

Remember flyover country? The coastal elites were supposed to have ignored it, paving the way for a Manhattan millionaire, Donald J. Trump.

With that election come and gone, try not to dwell on who had the saved the auto industry or the economy—or who had the better platform to address continued upheaval. Consider instead a group that does indeed vote liberal and dwell largely on the coasts, but also keeps crossing America. I mean artists, and some keep returning to the heartland. Donna Dennis takes a loading platform on the Great Lakes as inspiration for an installation with a view of the sky, while Greg Lindquist treats coal plants as another kind of flyover country, with paintings from afar or above.  Aspen Mays rides out a hurricane, and Sam Falls adapts photograms to life off the grid. They all find a dark and not altogether distant beauty.

Aspen Mays rides out a hurricane, and Sam Falls adapts photograms to life off the grid. They all find a dark and not altogether distant beauty.

A dock in the dark

Nothing quite prepares you for Ship and Docks / Nights and Days, an installation by Donna Dennis. If you know her only from the works on paper just outside, you may be totally unprepared for its mass. Even if you know her from past work, you may be unprepared for its changing light. If those sound like opposites, they sum up much of its presence and its mystery. An artist known for sculptural installations, she has added a video component, on top of the light from within. She has also brought you closer than ever to her bulky construction, while leaving open just how far it may reach.

The title, too, sums up both her subject and its puzzle. Is it day giving way to night or night giving way to day, and just how many nights and days? Where, for that matter, is the ship? The work lies beyond a black curtain, in a room that you might never have known was there. You must first pass through a bright, upbeat summer group show at that, fixed more on the human body than on passing ships and passing hours. It may come as a chastening darkness or a much needed rest.

The gallery links her to others of her generation in Alice Aycock, Jackie Ferrara, and Mary Miss. Each deals in sculpture and weight, but also in feminism and land art. Dennis, though, is not bringing art outdoors, but rather bringing the outdoors in. She represents a specific place that she knows well, Lake Superior. Her construction takes the shape of an ore dock—or loading platform for natural resources, for shipment to steel mills and the like. She is not making earthworks in the manner of Miss, Robert Smithson, or Walter de Maria, but rather recalling those who move earth for a living.

Not that she is all that literal, although she shies away from Aycock's abstraction. One finds oneself within reach of the work with no clear place to take its measure. (A real ore dock might reach half a mile into the water.) To someone new to steel country, home to LaToya Ruby Frazier, the crossing diagonals could belong to anything from an oil rig to a pier by the beach. Here they include a chamber fit for a watchman or a lighthouse keeper, lighted but strangely empty. It is just one of two structures, as it happens, one facing the viewer and the other away.

The works on paper give a preliminary view of the structures and the light. Points of light interrupt the gouache and points of black the paper, like pinpricks. They add luminosity and, by their resemblance to constellations, root the scenes in the imagination and the night. It may come as that much more of a surprise, then, when the sky behind the installation fills with a softer glow. Its yellows and blues play off against the artificial light of the two interiors. Together, they offer an extended view into the changing light.

Is it dusk or dawn? It may depend on when you enter and thus which comes first, day or night. The impression remains, either way, of an artist in control of landscape and light. It remains, too, of something almost too close for comfort but just out of reach. It feels like a stroke of luck to find the bench on which to sit. It may feel in turn like a disappointment to exit into plain old gallery lights.

Ashes to ashes

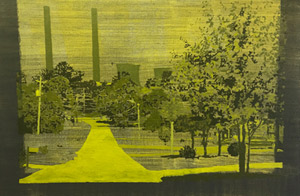

Greg Lindquist takes his brush to the largest coal electric plants in the United States. They are not, it appears, still generating much in the way of energy. They look toxic and empty, their surroundings overrun by weeds. They cannot manage sunlight or even a storm cloud, much less warmth or a shower. Landscape often gains from a winter chill, like trees in snow for Ron Milewicz. For Lindquist, earth and sky alike have given way to a dystopian gray, yellow, and green.

The culprit is coal ash, and he takes it as his medium as well as his subject. Lindquist often starts with a ground of ash mixed with acrylic, before painting in oil. Drawn-out brushwork makes scenes appear to dissolve before one's eyes. Smaller marks here and there bury things all the more. So does the jumble of towers, trees, and fences, at times holding the picture plane and at times messing with perspective. With or without energy, they glow.

The culprit is coal ash, and he takes it as his medium as well as his subject. Lindquist often starts with a ground of ash mixed with acrylic, before painting in oil. Drawn-out brushwork makes scenes appear to dissolve before one's eyes. Smaller marks here and there bury things all the more. So does the jumble of towers, trees, and fences, at times holding the picture plane and at times messing with perspective. With or without energy, they glow.

"Of Ash and Coal" took him to Texas, Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina, but it could pass for a single site. Everything holds the scene at a distance, from the foreground vegetation to the simulated wood frame in oil. The colors suggest another distancing as well, that of a photographic negative or Photoshop. Still, he wants one to feel the damage viscerally, quite apart from the contribution of carbon emissions to climate change. Breathing and contact with coal ash has taken its toll on health, including the health of workers who wish they could breathe more of it. With the paintings, the ash can still get under one's skin.

At the very moment of America's ascendancy in art, Thomas Cole could not get over his fears that its greatness had already past. Nor were his concerns for America alone. If anything, he looked to his adopted nation for more open vistas and clearer skies than he had seen in industrial England. He looked to its rivers and falls for an alternative to the fiercer currents that he so dreaded in British Romanticism. And he placed them front and center of the Hudson River School in American art. What, then, would he have made of coal country today?

Lindquist sees it as well past the point of crisis. Maybe Trump voters wanted back their job security and their unquestioned status, even as their region's economy had already moved on and their children had already moved away. Maybe Cole saw a human-induced apocalypse in the making in the skies of J. M. W. Turner. Forget it. Lindquist sees the drama as pretty much over and done. Yet he also sees an unnatural beauty worth contemplating.

The paintings look mildly creepy at first, but they get better with acquaintance. They show observation, but also artifice. In a photo, grass ameliorates the ugliness, and even fences look halfway inviting, but not here. Cole's successors brought a greater optimism, and then another generation, including Winslow Homer, learned a more homespun naturalism from the Civil War. Trump's party still benefits from one side in the war. If Lindquist has his way, both sides can benefit from remembering.

Stormy weather

As a tropical storm ravaged North Carolina, it was hard to overlook nature's power. It was harder still to grasp its enormity. Art can help, by insisting on the human power to build and to destroy—and how those powers are impossible fully to separate. Humans have devastated ecosystems in no small part through disease, invasive species, and climate change. Climate change and patterns of development have also increased the severity, frequency, and toll of hurricanes. Yet art has its own cycles of construction and erasure, and it can design for climate change and "Emerging Ecologies.

Aspen Mays pictures interventions to save businesses and dwellings in her hometown in the Carolinas—only not from Florence or Michael in 2018, but from Hugo back in 1989. Not even she could have foreseen how much her show's timing could reinforce its message. If she also has you seeing ghosts, she relies like Patti Hill on a ghostly process, photograms. And if it boggles the mind to place an entire storm or building up against photo-sensitive paper, she recreates them in her studio. They have a ghastly beauty, but then they are both ghosts and art. One might even mistake many of them for paintings.

They divide neatly in two. Ones on an easel scale in bright color look much like abstraction with elements of gesture and geometry. They also look hard and clear enough that one can make out the brushwork, except that it does not exist. Taller work signals its status as a photogram more clearly, with its grainy black and white. It is clearer about its subject as well—arched windows taped shut to minimize the damage. Given the association of arched windows with bare ruined choirs, right down to what could pass for stone frames, one can only expect a few ghosts.

Mays takes particular pleasure in how little the mandatory tape across windows can prevent them from shattering in high winds. She also seems to enjoy the irony that the arched windows belonged to a diner named California Dreaming. Still, this is not an exercise in futility. She comes at a time of the revival of painting, but also of the blurring of lines between representation and abstraction or photography and painting—as with Artie Vierkant, Sheila Pinkel, and Letha Wilson at the same gallery. The crossed tape can appear like asterisks, and light can gather at their centers to sparkle like stars. In color, sparser tape accounts for the appearance of a brush.

Sam Falls scrambles the photographic object further, by simulating photograms without a trace of photography. In a time worried about such things, one could almost call his work chemical free. He places pigment on canvas, overlays foliage, and exposes it all to mist, rain, and sun. Nature, he insists, does the dirty work through its circadian rhythms. If that recalls Autumn Rhythm, by Jackson Pollock, the single best work has an incredible mural scale. Come to think of it, a palette of fall and summer leaves defines abstraction and collage by Lee Krasner at her best, too.

Modernism, then, was already blurring lines effectively, but Falls is still a skeptic. He seems obsessed with beauty and not destruction, but not entirely. He speaks of work about "disuse," not a more idyllic concept of life off the grid. He pairs a photograph of his own with a cover by Ansel Adams, while other photos enhance the mirror tone of silver gelatin prints for more ghosts, including yours. He also presses objects into deliberately awkward ceramics, for a trendiness that I could live without. You may not have to wait long, though, for another storm.

Donna Dennis ran at Lesley Heller through June 30, 2018, Greg Lindquist at Lennon, Weinberg through April 14, Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris through February 10, Aspen Mays at Higher Pictures through October 27, and Sam Falls at 303 through October 20. The review of Lindquist first appeared in a slightly different form in Artillery magazine.