Who Will Inherit Art?

John Haberin New York City

Inheritance, Pepón Osorio, and Tuan Andrew Nguyen

Sadie Barnette would like you to make yourself at home, her home. She opens "Inheritance" at the Whitney with spray paint, photos, and a nice, plush sofa.

Not that you can sit in it, for this is after all a museum, but then you might not care to try. It looks comforting enough, but too tacky for words, in a silvery holographic vinyl speckled with rhinestones. So do the prints and posters behind it, which she claims to be a black woman's most precious memories. They look more like ads, although one bears her name in the garish font and colors of a birthday card. They might celebrate commercialism and family or back away from both. No matter, for both are her inheritance.

"Inheritance" takes its name from a film by Ephraim Asili, which plays out in an alcove near the end. The director charts his dedication to black power and the black arts, with archival and created footage, although a young woman in the film loses patience with them, too. (As a matter of fact, Barnette's father co-founded the Black Panthers.) A video by WangShu might be speaking for her when its narrator pleads for more than positive images. Yet the exhibition wants it both ways, critical but a celebration. It cannot get over painful memories, but it insists on a happy ending in the present.

Some artists create installations. Pepón Osorio brings an entire community to the New Museum, as "Mi Corazón Latiente," or "my beating heart." It is a Puerto Rican community, and its heart is still beating, but all is not well. At that same museum, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, too, knows for whom the bell tolls. He has sculpted an impressive one out of unexploded weaponry, the kind that still covers 80 percent of a province in Vietnam. Yet it tolls not death, but a healing note in Asian tradition—and who can say which will be his inheritance?

The extended family

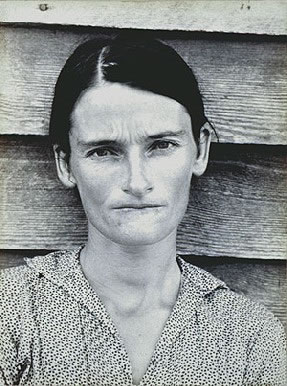

When Modernism vowed to "make it new," it turned from art about the past to art about itself, and Postmodernism repaid the favor by turning that lens on Modernism. Critics began to question the loss of its inheritance and "originality of the avant-garde." And the Whitney includes a foremost critic in Sherrie Levine—her photographs of photographs by Walker Evans. Decades later, that very criticism has become the good news, as exhibitions everywhere embrace diversity and its global heritage. What, though, does that leave for "Inheritance" beyond a highly selective and utterly superfluous recap of art today? What, too, if that recap is painful, prefabricated, and commercial?

They say that charity begins at home, and the curator, Rujeko Hockley, begins with family. The first room centers on Mary Kelly, whose 1973 film lingered over a woman's belly in the final moments before birth. (Hey, we all have to come from somewhere.) A father figure makes his appearance in film by Kevin Jerome Everson, blowing out the candles at age ninety-three, but mothers abound. Bruce and Norman Yonemoto mix up their personal histories with cigarette commercials, much like Sadie Barnette, but they, too, are enjoying themselves. If your childhood was anything but happy, do not look to the Whitney for support.

Theaster Gates and LaToya Ruby Frazier have traced African American history through family and friends, while museums have singled out the Black Arts Movement and a legendary black-run gallery. Sure enough, two more rooms cover African Americans and the "global South." Todd Gray manages to sum up the entirety of colonialism in a single photo collage. An-My Lê drapes a banner across a statue of a Confederate general. Could, though, an artist's greatest inheritance be art itself? A room in-between picks up on Modernism and Minimalism, with a smashed tube chair from Wade Guyton, a silver striker by Hank Willis Thomas, and a red curve after Ellsworth Kelly by Carissa Rodriguez, cast in salt.

Still, what is the point? Surely others have had had equally moving accounts of Africa, slavery, and Black Lives Matter. And has any artist not looked back, like Cecily Brown to Flemish still life? Should artists be proud of their inheritance or ashamed? And what will others inherit from them? As it turns out, a lot, and it does much to redeem a confused and confusing show.

These are vivid memories, in all their pleasure and pain. Beverly Buchanan recalls the rural sheds of her ancestors, Mary Beth Edelson their mothers and gods, John Outterbridge their prayers and their dance. In a five-channel video, silhouettes and stereotypes from Kara Walker come to life. On the dark side, Faith Ringgold maps the United States of Africa, while Cameron Rowland recreates police radio, in all is racism. Kambui Olujimi pictures forced labor beneath a darkening sky as ghosts. Ana Mendieta leaves her impression in shifting landscapes and unsteady sands.

Just as much, one can relish the ambivalence. Lorraine O'Grady does, in her white dress and witty incursions into Central Park. So does David Hartt at the publisher or Ebony and Jet, where African art looks ever so forlorn. So, too, does Sophie Rivera, whose photograph of a child never quite emerges from its shadows and reflections, as I Am U. That video by WangShu lingers over luxury high-rises, cut off from the life below. Yet every so often the glass of their towers allows a view through to the sea.

From installation to community

Installation art can create a world to itself, the world of art and performance. Not for Pepón Osorio, despite a background in performance art. He takes an entire floor of the museum for a bedroom, a living room and dining room, a prison cell, a trailer, and a classroom. Many a community has a barbershop or a pool hall as its meeting place, and he devotes his largest installation to them. A shed reminds him of a woman he saw selling shaved ice. If individuals are their inheritance from family, ancestors, and community, as in "Inheritance" at the Whitney Museum, this is his beating heart.

What are a pool table and hubcaps doing in a barbershop? All are welcome here, with flowers, and old-style photos in oval frames give them all an inheritance. Jesus himself makes an appearance, with a pet dog. The porcelain miniatures on a busy shelf add up to a wedding dance. Still, Osorio is not celebrating. If nothing else, he is too obsessive to stop collecting, and cheesiness is his inheritance, too.

The show's title work, a heart as large as he, has a cheerful red and, in all, the colors of the Puerto Rican flag. Still, its anatomical correctness is unsettling, and it hangs from above like a piñata, with a crepe-paper coating. If this is a beating heart,  it can also be beaten. Too many, Osorio makes clear, have already taken a beating. That shed leans on dozens of crutches, and the woman in a photo inside looks close to tears. For the Puerto Rican artist, it is the Lonely Soul.

it can also be beaten. Too many, Osorio makes clear, have already taken a beating. That shed leans on dozens of crutches, and the woman in a photo inside looks close to tears. For the Puerto Rican artist, it is the Lonely Soul.

That living room and dining room stand behind yellow police tape, with a blood-stained sheet and an unnerving clutter, as Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) Osorio is not answering, but he is definitely accusing. Many of the installations exhibited on-site in Puerto Rican neighborhoods from New Haven to Philadelphia, where the artist lives and works. Yet a painful story lies behind each one. The classroom first appeared in a shuttered classroom, the barbershop in an abandoned barbershop. The bedroom stands adjacent to the prison cell as Badge of Honor, but it is a badge that I, for one, should not wish to wear.

Still, as the title of the barbershop has it, No Crying Allowed. He has also served as a case worker in child services in the Bronx, and he is not just looking back. He calls his latest work Convalescence, although I cannot say whether the mannequin at its center is a prisoner, a patient, or a superhero. (One encounters its garlic bulbs, empty bottles, and pill cases right off the elevator.) For the community in Newark, Osorio says, having a father in prison is a badge of honor. The show's very overkill brings a degree of joy.

Not that Osorio has changed much since the crime scene appeared in the 1993 Whitney Biennial. (The biennial was the subject of one of this Web site's first reviews.) Dates add little to a show without regard for chronology, curated by Margot Norton and Bernardo Mosqueira. His installations also have much in common with domestic interiors in Caribbean art at El Museo del Barrio. The threat to the community recalls the threats of colonialism and hurricane damage in Puerto Rican art recently at the Whitney. He has been collecting objects and memories for a long time now, and it shows.

It tolls for thee

In "Inheritance," an artist's inheritance is a simple matter of pride. How does that apply to a country after nearly fifty years of Communist rule and, before that, thirty years of colonial and civil wars? Tuan Andrew Nguyen still asks for healing in a divided nation. Born in Saigon in 1976, barely a year after the city fell to the north and the last Americans were airlifted out, he lives and works to this day in what is now Ho Chi Minh City. Yet he cannot forget what he himself never knew. It has become, in the exhibition's title, his "Radiant Remembrance."

It is a show of shared memories and contested ground, going back to the first Indochina war, from 1946 to 1954, when the French conscripted men from its colonies in Senegal and Morocco as tirailleurs—riflemen, sharpshooters, or snipers. The word sounds ever so quaint for forced labor in a deadly modern war. The soldiers brought death to families like those in documentary photos covering a wall at the show's entrance. Some still seek acceptance and forgiveness. To judge by Nguyen's videos, it will come willingly but not easily. The very titles speak of little else, as The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon, and Because No One Will Listen.

Taken together, the three add up to the length of a feature-length film, and one can only wander among them as across unexploded mines, wondering what one has missed and who will survive. In the longest, a man begs for a young woman's understanding, and she herself comes under harsh questioning from others. In a four-channel video, speakers at a microphone speak for the resented and forgotten while rapt faces take in the broadcast. In the last, a woman recites a letter to her lost father, while the images speak to a treacherous landscape of soothing waters and bare, twisted trees. Not everyone would want to claim this inheritance. Many have no choice.

For Americans, the Vietnam War is something to forget. Back then, it was either a brave fight against world communism or the arrogance of a global empire, with little to say for the Vietnamese themselves. For Nguyen, America's incursion was only a blip in a longer domestic conflict. His videos never once mention it, although its impact is everywhere. He is hardly the only one to have "repurposed" mines and bombs. As art, though, they take on unexpected resonance. They ring out with allusions to the United States.

Unexploded Resonance recalls the Liberty Bell in its scale and wood armature. It might also look at home at the Isamu Noguchi Museum were the found wood not so ornate. Other ordnance has become simulated Calder mobiles—or what Alexander Calder might have produced had he cared for polished metal and reflected light. Nguyen has an eye for beauty, just as he has an ear for shame. Is he also taking a shot at Americans who never seem to know how to listen? Maybe, but not entirely, and he alludes to Vietnam as well.

As curated by Vivian Crockett with Ian Wallace, the sculpture could serve as props for the videos. They continue the story as well. The mobiles hint at celestial bodies, with titles like A Rising Moon Through the Smoke, Firebird, Rolling Thunder, and Starlite. A Buddhist god in carved wood has golden prostheses for Nguyen's shattered arms. Can the bell really sound a healing note? Across from video, it is notable for its silence.

"Inheritance" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through February 4, 2024, Pepón Osorio and Tuan Andrew Nguyen at the New Museum through September 27, 2023.