After Subtlety

John Haberin New York City

Kara Walker, Sanford Biggers, and Nina Chanel Abney

Kara Walker is out to try your patience. Her very title sounds like the words of a carnival huckster, and one hardly knows where the boasting stops and the irony begins. And yet few other artists can convey both in so powerful a work.

An absence of lowercase letters turns up the volume that much more, but allow me to supply them to stay halfway sane: "Sikkema Jenkins and Co. is Compelled to present The most Astounding and Important Painting show of the fall Art Show viewing season!" So there. The funny thing is that it may well be true. Sanford Biggers and Nina Chanel Abney do their share of boasting, too, as African Americans and speak to their share of anger and fears. If I were you, I would listen.

Students of color

With Kara Walker, it is hard to say, too, where the long title leaves off and the press release begins. "The Final President of the United States will visibly wince," she concludes. "Empires will fall, although which ones, only time will tell." Plainly she, too, is losing patience, like so many others in the age of Trump. Sketching in ink, often on mammoth sheets of paper, she seems barely to keep up with events or her outrage. Her loosely assembled figures become collectively a game of "Where's Donald," as in "Where's Waldo" for a child president.

Walker is just as impatient with her audience. "Students of Color will eye her work suspiciously and exercise their free right to Culturally Annihilate her on social media." She speaks as the artist whose plantation stereotypes in silhouette made her career, much like Robert Colescott years before her, but seemed to critics a passive acceptance of what she hated. She has defended Dana Schutz, a white artist who tackled the death of Emmett Till in the 2017 Whitney Biennial—and Till's corpse, wrapped like a mummy, may pass through this show as if rescued from a burning building. Walker spoke as a defender of artistic freedom, but she was speaking from experience. And experience is a harsh master, because the lynchings and other violence in her drawings seem all too contemporary and all too real.

Her critics have always missed the point. Not every African American has to offer role models in her art. Portraits by Titus Kaphar or Kehinde Wiley are cheerful enough, but racism is not pretty—no more than Till's mutilated face in an open casket. Neither, for that matter, is anger. Walker has a respect for history, but also the fierce energy of now. She has not lost her sense of humor, not with a New Yorker cover based on Washington Crossing the Delaware, but she is feeling the pain.

How much has she changed since her plantation days? She is glad you asked. "Art Historians will wonder whether the work represents a Departure or a Continuum." The silhouettes reappear in one work, but on white linen whose ripples shine. A few drawings appear on linen, with oil stick. Dredging the Quagmire puns on Trump's promises to drain the swamp, but its opaque background makes a woman's struggle to escape the quagmire seem that much more desperate. They make a point of their hasty or unruly assemblage, with hardly a trace of color but with plenty of heat.

They also make a point of their knowledge of art history, including white art history. Titles allude to Edward Kienholz and Albert Pinkham Ryder, in a spirit of tribute as well as mockery. The Pool Party of Sardanapalus combines the tawdry affairs of suburbia for Eric Fischl and an Assyrian king's harem for Eugène Delacroix. Christ's Entry into Journalism has a predecessor in Christ's Entry into Brussels, by James Ensor in 1889. Walker's carnival of death looks almost restrained by comparison, but barely. Just try to spot Martin Luther King, Jr., and Frederick Douglass with a Black Power salute—and try to decide who has the last word.

Work like this has to bear a lot of weight, and Walker has mixed feelings about that, too. After the boasting comes an "artist's statement," in which she sounds "tired, tired of standing up, being counted, tired of 'having a voice' or worse 'being a role model.' " If her compositions fail to cohere, she may have meant it that way. A prominent critic's demand that the work go on permanent display opposite Washington Crossing the Delaware, in the Met's American wing, sounds downright laughable. After a sphinx-like sculpture in sugar, as A Subtlety in 2014, she may be happy to dispense with permanence. With the factory that housed it gone and the powdered sugar lost to the winds, who knows how long the authority of art or this administration will remain?

Understated and overstood

Sanford Biggers wants you to listen. He punctuates his latest work with gunshots—and his images with torn bodies, towering fields of black, and colors running every which way. With one major party giving aid and comfort to bigots and Neo-Nazis, he evokes everything from African totems and decorative arts to Black Lives Matter. Yet he also challenges one to pin any of his images down. On top of that, he calls the show and its centerpiece Selah. Sometimes it takes courage to resist interpretation.

That centerpiece is larger than life, but only barely, and other work may run comically small. Selah stands nearly eleven feet tall, but only because the human figure has its hands raised, either to avoid a deadly police response or in the throes of death. Patches of red, white, black, and blue heighten its jagged outlines, and one lower leg is entirely shot away. A bronze head on a pedestal shows off a bullet hole more directly, in place of an eye. The flat bronze recalls African art and the "primitivism" of early Modernism, and the single eye more reasonable in a profile connects to Cubism as well. Someone might have taken a gun to a museum artifact or a human being, but then art may disfigure the humanity of others, too.

Overstood combines the show's scales, leaving it to the viewer to decide whether Biggers has overstated or understood. A black triangle connects three small African gods on the floor to the black outlines of four men on the wall, like enormous cast shadows. Do they draw on iconic photographs of black activists forty years ago? Should one be worshipping gods or men? Gunfire rings out regularly in a video of still more totems, its five channels blinking on and off in a further rhythm. Yet the monitors receive a kind of demotion, too, relegated to leaning up against a corner.

They also bear glimpses of landscape and the title Infinite Tabernacle. Registering the past does not exclude the possibility of renewal. The bright colors of Selah derive from tapestry, and actual tapestry goes into wall pieces—along with charcoal, acrylic, mirrored tiles, and gold leaf. Sources range from Japan and Egypt to America more than a century ago. To trust the artist, they served as markers for the Underground Railroad. With work so all over the map, I can promise only so much.

Speaking of resisting interpretation, you may remember selah as a refrain of uncertain meaning in the Psalms. After years of rock concerts, I want it to signal a guitar break or an invitation to audience response. And his show at SculptureCenter in 2011 went for volume. Maybe Biggers is learning eclecticism from Rashid Johnson or reticence from David Hammons. Maybe he could agree with Walker in refusing to stand for a people or a generation just a few blocks away. Still, selah.

Leslie Wayne has a taste for African tapestry, too. She appeared just this year in "Africa on My Mind" at the Houston Museum of African American Culture. Still, she is using the decorative arts much like Biggers, to unsettle abstract painting, with its own refusal of interpretation. A white artist born in Germany, she paints and rubs away at her painting, crinkles it up, and attaches it to more painting. It may fold over the top of the backdrop, as if hanging out to dry. Even routine geometry and gesture can be an opening onto multiple cultures—or an opening into the third dimension.

Trigger warnings

Nina Chanel Abney comes with a warning. Given the necessity of Black Lives Matter, make that a trigger warning. That could explain the choice of signs that Abney has adapted many times over for a two-gallery show of paintings. Get help, one painting screams in capital red letters. Get first aid right away, runs another. Trouble comes when you delay!

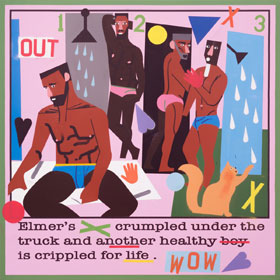

Trouble is coming anyway, and Abney is a worthy troublemaker. The works at her first gallery stick to a poster format, right down to their flat renderings, routine fonts, and plain, slim frames—and then she messes them up in all sorts of ways. The fonts may shift even within a line, and their message may veer off just as suddenly as well. Someone has added text here and there or effaced it, and it is hard to know which amid so many cross-outs and underscores. They could show off a graffiti artist or an ingenious designer. The frequent X-marks could stand for further erasure or love and kisses.

Trouble is coming anyway, and Abney is a worthy troublemaker. The works at her first gallery stick to a poster format, right down to their flat renderings, routine fonts, and plain, slim frames—and then she messes them up in all sorts of ways. The fonts may shift even within a line, and their message may veer off just as suddenly as well. Someone has added text here and there or effaced it, and it is hard to know which amid so many cross-outs and underscores. They could show off a graffiti artist or an ingenious designer. The frequent X-marks could stand for further erasure or love and kisses.

Color runs wild, too, from bright backgrounds to a colorful cast of characters. Even those frames contribute with their mix of black, green, red, and blue. Most of all, the message keeps changing before one's eyes. A black couple walks their dogs in sunlight, but the silhouette of another creature lies below them, RIP. It's great to be alive, another work announces above joyful or angry birds and an athlete literally tied in knots. Yet a cross-out has either upped the ante from be alive to live—or else paused for a moment in the middle of denying life.

Characters are running around in swim trunks, showing off, supporting one another, or breathing a sigh of relief—but one, the text explains, lies under a truck, one will have to spend a month in the hospital, and another is crippled for life. The ambiguities extend from the message to its audience as well. One painting could be preaching mutual respect or every man for himself, with watch out for the other guy! But then the paired signs beneath for uh oh black and oh no blacks could remind blacks to watch out for the cops or whites to watch out for who is taking over the neighborhood. Both, of course, are signs of racism aimed at African Americans, but the paintings speak more of joys and sorrows than of anger or fear. They are too alive, too aware of the hormones in her largely male cast, and way too busy messing things up.

The poster style, dry humor, and grim politics recall Barbara Kruger as well as black artists concerned for police killings like Sanford Biggers, Carl Post, and Arthur Jafa. Like her, Abney turns appropriation into a signature style. Kruger should receive credit if not a copyright fee every time an ad overlays text in bands of red—and for all I know she does. Abney, though, has another model, too. The X's, O's, overlapping color fields, and sheer exuberance recall Stuart Davis. Her WOW here and there shares his amazement at that.

She approaches Davis all the more in her second gallery, where her posters give way to murals. His thoroughly American Cubism anticipates Pop Art, and she is both looking around her and looking back. These paintings run denser and even wilder, with men crowding in and strutting their stuff. They take place in the here and now of a 99¢ store, but also in the belligerence of the imagination. The curator, Piper Marshall, moves from the first gallery's "Safe House" to the second's "Seized the Imagination." Abney still, though, has her signature X—and, here and there, a determined NO.

Kara Walker ran at Sikkema Jenkins through October 14, 2017, Sanford Biggers at Marianne Boesky through October 21, Leslie Wayne at Jack Shainman through October 21, and Nina Chanel Abney at Mary Boone through December 22 and at Shainman through December 20. Related reviews look at Kara Walker in retrospective and in sugar.