Journeys Toward Freedom

John Haberin New York City

Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series

Wassily Kandinsky: Compositions

Horace Pippin: I Tell My Heart

Which would you choose? To the left, three crucial decades in the evolution of abstract art. Buffeted across Europe, Wassily Kandinsky (well, Vasily to one museum) in his Compositions poured the spirit of his culture onto ten sweeping canvases. Some have never been seen in America. Others were destroyed and may only now be studied from sketches and photos gathered here.

To the right, sixty folk-like images by a young African-American.  Born in the shared hopes of the WPA, Jacob Lawrence's 1941 series is at last reassembled. It is the artist's grave testimony to the trauma of a nation and the experience of his race. For me it dwarfed a show, running concurrently at the Met, of another important black artist, Horace Pippin.

Born in the shared hopes of the WPA, Jacob Lawrence's 1941 series is at last reassembled. It is the artist's grave testimony to the trauma of a nation and the experience of his race. For me it dwarfed a show, running concurrently at the Met, of another important black artist, Horace Pippin.

Door number 3?

It sounds like an allegory of Postmodernism—high and low, the avant-garde and populism, purity and politics, Europe and the American century. The choice is real. The two shows at New York's Museum of Modern Art run concurrently. Their doorways lie side by side. I could spot couples separating on their way past.

Jacob Lawrence traces the black migration north just after World War I, two decades before Walker Evans would travel south to discover the dignity and desperation left behind. The scenes start with decaying resources and stark racism in the rural south. They set a standard for the South in American art to come, as they take up the Great Migration, hardships of travel, and new urban vistas. Repeated motifs, such as train stations and arrivals up north, punctuate the epic narrative. They end on a treacherous independence amid a different sort of racism.

The Compositions, in turn, offer a chance to rediscover Wassily Kandinsky without a trip to the Munich or the Hermitage. As a New Yorker, I knew the second from a small oil, a sketch in the Guggenheim. I could never have imagined where it was to lead. As with Lawrence's migrants, the price of freedom is that one may not find one's bearings. I also know no better evidence for why abstract art stays provocative—on museum walls and in the hands of younger artists.

The allegory is only fitting. Postmodernism, after all, has agonized over choices exactly like these. It has also revived the very credibility of allegory, after decades of more allusive forms. (But then Jan Vermeer, a modernist icon, created his allegory of painting, too.) It has encouraged exaggeration, like the rhetoric with which I myself just began.

Alternatively, a proper postmodernist might turn away from either choice. Both are visions of salvation. Racism and a loss of faith in art's spiritual value or the "spiritual in art" have outlasted the optimists. They have driven black Americans into silence and exile. The have made black artists question the whole idea of African American art, but not its absence, invisibility, or erasure.

Yet the exhibits have something in common—and not what one might expect. Taken together, they cast doubt on easy oppositions like high and low culture. They also make a case for a darker, more complex modernist vision. You cannot turn your back on either unharmed.

Modernism, racism, and anonymity

Lawrence's narrative may sound like an excuse for pieties. The artist, one ought to remember, is triply armored. He could rely on the WPA and two subsequent commissions, plus a boost from an innovative American art dealer in Edith Halpert—as just the start of a long career. He had the virtue of his people—and a distance of twenty years.

Lawrence was born only in 1917, when his series opens, and raised in Harlem. MoMa attempts a context in African American culture there, including music and books. (Wall labels for photography, despite some stellar photographers, stick strictly to their subjects.) He learned history in part from government-sponsored studies. No wonder his titles seem, at least at first, to enjoy the reassurance of a past tense, like After a Lynching the Migration Quickened. And I, for one, am glad.

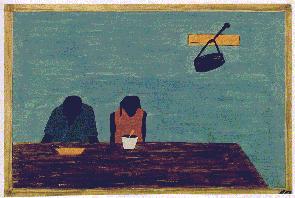

The Migration Series brings its pieties home, because the painter had so little to prove. He exhibits no conflict between trained art and plain images. Both led Lawrence to small panels, with evenly applied oil and tempera on board, although sparer brushstrokes evoke the coarse textures of raw wood. His irregular curves and jagged corners might equally echo folk art or Cubism. Both collage and old-fashioned stories also support a combination of text and art. The titles for each panel, placed just above, guide visitors along.

Yet Lawrence's synthesis makes these messages oddly disturbing. Untrained art usually centers around the human form. In his asymmetric designs, though, the figures are all but lost, for all their hats set like haloes, their bare-chested labor like that of the Jews as slaves in Egypt, and their ultimate exodus. Black dominates, and not as skin, here painted brown. Along with the equally flat yellow, red, and green, it evokes heavy clothes, dried earth, and airless factories. The colors unify the series with the pride of an emblem and the pitilessness of poverty.

The thin, dry color made me note an insistent clash between titles and scenes. In one early panel, the sun brings promising streaks of light. Then I looked up and read: the fields are barren, driving hungry families north. Conversely, Lawrence's anonymous forms do little to make messages of family feeling and mutual sacrifice any too comforting.

About midway through, the migrants reach north, like Kerry James Marshall decades later. The titles announce new creature comforts, but these apartment blocks look just plain menacing. Later, when one can finally make out a few faces, the titles bring reminders of persistent racism. The past tense, attached now to voting rights, starts to sound dismaying.

Composition and freedom

Without question, Wassily Kandinsky meant his ten huge canvases, each one called Composition, to soar. Colors become intense primaries, filling in the sketchiness of the early drawing. The handling varies from thick streaks to a characteristic soaked color, almost like watercolor. The dense drawing links the earlier schematic images, carries the eye past them, and finally buries them in a torrent of color. Lawrence, I had to admit, could hardly have dreamed of this virtuosity.

Scale matters, and not only because the size is overwhelming. Remarkably, the edges no longer frame a window—not even a window into the psyche. In the open fields, an afterthought can easily become a further layering, like graffiti. When Abstract Expressionists imposed a Cubist grid, they gained in formal structure. They also put a viewer squarely and provocatively inside the work. Yet they overlooked Kandinsky's openness, which still seems relevant today.

Nonetheless, Kandinsky's promise of liberation has built-in limits. Consider his dependence on myth. His smaller paintings grew out of images of nature. As early sketches and photos make clear, the first Compositions began instead with an apocalypse. All the right attributes appear—floods, chasms, riders, chaos—and disappear.

To some critics, symbolism gives the game away. Abstraction merely exchanged one escapism for another. Kandinsky, they argue, has every reason to retreat to religion, like Mark Rothko to his curiously secular chapel. He came to painting too late in life to outgrow old-world values. He even left Munich right around the first Composition to reclaim his property rights.

Yet the images do not just fall back on tradition. They are narrative, open to anyone. Like Lawrence, Kandinsky at first saw little conflict between folk tales and fine art. In abstract art too, he boasted of something as universal as a triangle.

Moreover, the paintings refuse any final deliverance. Perhaps in his writings, like Lawrence in his titles, Kandinsky associates art with spiritual redemption. I pored over these sketches and never found it. Even as tormented a soul as Bosch included a savior with the last judgment. This modernist, never much for anxiety, does not.

Untitled myths

In the last Compositions, Kandinsky is still seeking that universal language without a net. His well-known turn to geometry removes even the enthusiasm of saturated color. I do not like the turn. I miss especially the earlier surfaces' affinity to American art of the 1950s. Still, I could finally understand something of its internal logic, the logic that drove Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim to found a Museum of Non-Objective Painting.

I could also see new connections between these stages. The earlier paintings place close transitions of color against the sketches' underlying drawing. In reversal, the later ones place geometric outlines against closely matched fields of color. Some painters may use shades of gray. Kandinsky paints in shades of black.

After all that, it is only fair to report that this exhibit overstates its claims. This handful of works are not the only ones that matter, or even necessarily the best. I doubt that Kandinsky meant to grade his work, with Composition for the A students. If the title suggests his art's insistent music, it is also a synonym for "untitled."

The hanging also let me down. I am used to having to jockey for position in front of a painting. Here adjacent walls get in each other's way, too. It also takes too long to figure out what wall of studies goes with what final canvas.

If the show cannot claim to be a career retrospective, it is at least a terrific concentration. Like Lawrence in his series, Kandinsky puts viewers through the wringer but, ultimately, left on their own two feet. No wonder his writings praise Picasso's stylistic inconsistency. I could begin to see why the completed Compositions pretty much ditch the narrative entirely.

I started with Postmodernism's appreciation of allegory. But Kandinsky is not replacing a myth by another, the myth of abstraction as high art. He is seeking an art that has room for moral suasion, but not for comfort. His Modernism is the myth of the irrelevance of myth.

Postscript: Pippin's subtleties and pieties

An older and more famous contemporary, Horace Pippin, also admired folk art. However, Pippin tried to bring sophisticated draftsmanship to simple conventions. His stories offer obvious heroes and villains—John Brown or "Mr. Prejudice." Religion has a central place as a source of common wisdom, black or white.

At his best, Pippin supplies a subtlety Lawrence lacks. His lighting has clarity and tonal variety. Ironically for a painter in search of past pieties, it echoes the best American artists of the 1930s. Pippin's self-deprecation, as a young soldier or old man on a park bench, is funny and disarming. Too often, however, as evident in a current well-planned retrospective at the Met, Pippin's innocence amounts to sentimentality. I knew he knew better.

Lawrence was never half as good in one painting. A series, however, let him handle far more stubborn truths. The visitor is obliged to follow in sequence through this well-spaced show as if sharing in its difficult voyage. At the end, a people has gained freedom through collective acts—but only the freedom to stand up to a persistently harsh, racist society.

"Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series" ran through April 11, 1995, at The Museum of Modern Art, where "Kandinsky: Compositions" ran through April 25, 1995. "I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin" ran through April 30, 1995, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Lawrence's series, normally split between New York and the Phillips Collection in Washington, returned to MoMA twenty years later along with other works through September 7, 2015. I have resisted the urge to start over, but I did revise and expand this, in the course of abridging it in a blog post for the occasion. Related reviews look further at Wassily Kandinsky, Lawrence's "American Struggle," and Jacob Lawrence in retrospective.