The American Half Century

John Haberin New York City

Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art

Labyrinth of Forms: Women and Abstraction

If "Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art" at the Jewish Museum looks familiar, it should. As a dealer, Halpert did as much as anyone to put a new American art on the map. She has left her mark even today.

Jacob Lawrence's Migration Series hangs in full at the Modern, just as it once hung above her fireplace. Why, then, can she often stop just short of a more radical Modernism, for all her work's innovations and pleasures? Is it simply a matter of a decidedly American art?  For "Labyrinth of Forms" at the Whitney, it was also first and foremost a women's art. Yet it, too, stops short of a breakthrough in modern art, for a nation and for abstraction. Just that offers insights into a pivotal moment and what held it back.

For "Labyrinth of Forms" at the Whitney, it was also first and foremost a women's art. Yet it, too, stops short of a breakthrough in modern art, for a nation and for abstraction. Just that offers insights into a pivotal moment and what held it back.

America for everybody

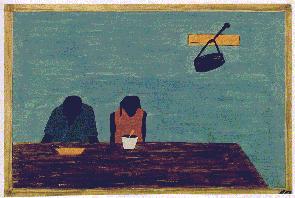

Edith Gregor Halpert exhibited an emerging American Modernism from the very opening of her Greenwich Village gallery in 1926. She exhibited Charles Sheeler, Eli Nadelman, Marsden Hartley, and Stuart Davis, including his jazzy odes to eggbeaters and Champion sparkplugs. She boosted Arshile Gorky and Edward Hopper as well, although mostly in prints. She took on such African American artists as Jacob Lawrence and Horace Pippin before diversity was the name of the game. Lawrence's epic series did indeed cross the wall above her fireplace in 1941. Unlike MoMA, she took care to exhibit it as a single row.

She gave equal weight to the social realism of Ben Shahn and O. Louis Guglielmi and the "magic realism" of Paul Cadmus and Peter Bloom. She exhibited folk art as well, long before it became newly fashionable as "outsider art." Has it since become an open challenge to formalism? But then Modernism, too, then was still the outsider in a proper textbook history of art. She was born in present-day Ukraine in 1900, at the very dawn of a new century, but she was determined to make it an American century as well. It is not too much to say that she succeeded.

Success did not come quickly or easily, in a New York that had not learned its lesson since freaking out over Modernism at the 1913 Armory Show. Not one painting sold in her first show of Davis—and the Depression only made things worse. Still, Halpert did well enough to buy a town house for her gallery on East 51st Street in 1940, to be closer to clients and competitors, and the surging wartime and postwar economy made things better still. If she was out to spread the word, so was her first major collector, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, with major donations to MoMA and the Whitney. Halpert was a collector, too, and her collection itself spread at auction after her death in 1970. Rockefeller Center hosted her art as well.

It took real savvy to pull things off. Halpert started in marketing as a teenager at Macy's, and she approached art as mass marketing. She opened the Downtown Gallery downtown, where housing was still affordable, and she promoted art as affordable, too. She argued for it as a Christmas present instead of a fancy car or radio, and she held a show of prints each December to bring the point home. She had little interest in postwar art, but she was delighted to claim Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings as precursors to Abstract Expressionism and Charles Demuth to Pop Art. She took just as much care in marketing herself to artists, exhibiting John Marin in order to woo him.

Still, "art for everybody" was not just a strategy, but also a commitment. Halpert doubled down on African American art in the face of racism, on Yasuo Kuniyoshi in the face of internment camps for Japanese Americans during World War II, and on everything in the face of McCarthyism. Folk art appealed to her as an art of, by, and for the people, although she exhibited the sophisticated trompe l'oeil of William Harnett and Raphaelle Peale from the nineteenth century as well—and she relished the parallels in Sheeler's patterned interiors and Nadelman's carved wood. She hardly minded, though, that images like Peaceable Kingdom, attributed to Edwards Hicks, came to stand for America. She worked with the government's Advancing American Art program to promote that image overseas. Critical theory today might see her populism and nativism as all too close or in conflict, but Halpert did not.

Why, then, have you not heard of her before? The curator, Rebecca Shaykin, finds an answer in her gender and willingness to credit others. Yet she was also a creature of her moment. She was hardly the only or most advanced American dealer or collector, not after Gertrude Stein in Paris or Alfred Stieglitz downtown—although she did her best to poach O'Keeffe, Marin, and Arthur Dove from Stieglitz after he died and his gallery closed. Halpert never lost her faith in realism, earth tones, and easel painting, just when painting was going abstract, bright, and big. She kept her distance from European art for good reason, but it also kept her in an American half century.

Ariadne's thread

You may know the Labyrinth of Greek myth not for its ingenuity, but as a contest of male will. How fitting that now the Whitney claims for women the path to an independent American art with "Labyrinth of Forms." In case you have forgotten, Daedalus, the very archetype of creative genius, designed the Labyrinth to house the Minotaur, who fed on human flesh—and from whom, like the maze itself, there was seemingly no escape. King Minos of Crete commanded it, but Theseus slew the beast, winning Ariadne, the king's daughter. But then the bull that fathered it with the king's wife had his desires as well. It took a woman to outsmart them all.

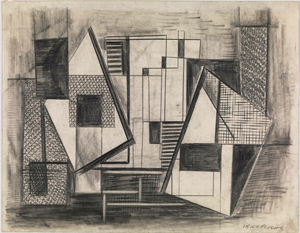

Ariadne, you may recall, saw that a mere thread could mark the path to freedom, but could twentieth-century women escape the labyrinth? The show starts in 1930, when Cubism still served as a model or a trap—and it ends in 1950, when many a history of American art is just getting underway. The curator, Sarah Humphreville, points to American Abstract Artists, founded in 1936 as a haven for abstraction under assault. It also gave women a place to thrive. So did works on paper, and the show singles out Atelier 17, a school and studio for printmaking as well. It helped make Greenwich Village the scene starting in 1940, well before Willem de Kooning and the crowd at the Cedar Bar got going.

The Whitney sticks to just over thirty prints and drawings, all of them by women. It was collecting them well before the fashion for recovering unfamiliar names. It can make its case with Alice Trumbull Mason, a founder of AAA who had her own Labyrinth of Closed Forms. (Her daughter, Emily Mason, and Merrill Wagner, an emerita member, have a case to make today.) The sheer number of women makes an impact as well. Like Dorr Bothwell, who founded a Bay Area collective, women often recalled the casual sexism and the pressure to join in with sex and drink.

A show this focused can deliver only so much. One might never know that AAA had more than forty founding members, most of them men, including Josef Albers, Burgoyne Diller, Balcomb Greene, and Ilya Bolotowsky, and Ad Reinhardt soon signed on. For them, too, Cubism could be a trap, one that postwar art was delighted to escape. Even at its best, the show falls for the finicky line of prewar art, including abstraction by Perle Fine and still life by another founder of AAA, Rosalind Bengelsdorf. One of the densest and most welcome, Irene Rice Pereira, returns to another device of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso as well, the illusion of chair caning. Nocturne by Dorothy Dehner could well be a study for wire sculpture.

Works on paper have their limits, too. One may remember those years more for WPA murals by Bolotowsky and others, with a scale that inspired Abstract Expressionist New York. While some break with Cubism, the break has its problems as well. Cubism's punning exploration of fictive space is largely gone. Elaine de Kooning is among the closest to Cubism here in everything but humor. But then try to find a sense of humor in Jackson Pollock and his peers apart from, just maybe, de Kooning women.

And yet something was coming to be, including a woman's art. Printmaking takes craft, and Anne Ryan brings an unexpected softness and color to woodcuts. Surrealism enters abstract art for Charmion von Wiegand, much as for Arshile Gorky—although it also held Pollock back. Lee Krasner pulls off simple primary colors as early as 1938, in a wide-open space that Jackson Pollock himself did not yet know. Louise Nevelson reduces drawing in 1934 to a single curve doubling back on itself again and again. It could be Ariadne's thread and a way out.

Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art" ran at the Jewish Museum through February 9, 2020, "Labyrinth of Forms" at The Whitney Museum of American Art through March 13, 2022. A 2022 exhibition rehangs the Whitney's early modern art with an emphasis on diversity, as "At the Dawn of a New Age."