The Menaced Assassin

John Haberin New York City

Joan Miró: Painting and Anti-Painting

From 1927 to 1937, Joan Miró dished out a history in brief of modern art. For Miró, everything was possible and nothing was satisfactory. In a survey of the decade at MoMA, everything was also more than satisfactory, and meaning is in hot pursuit.

Fighting back

"I want to assassinate painting," he said, and he did not lack for murder weapons. Joan Miró stripped painting down to little more than bare fabric and a splotch of white paint. He soaked it in oil, buried it in tar paper and linoleum, and crowded it to chaos. He stuck a sheaf of rope at its center, tightly wound as if for a hanging. He gave up on it entirely here and there.

For all that, painting kept fighting back, and so in turn did he. MoMA calls its show "Painting and Anti-Painting," but a title from René Magritte might do as well, The Menaced Assassin. At the very least, it makes for a compressed but vivid alternative to a career retrospective. One who knew Miró only from his rigid early portraits might mistake him for a folk artist. One who knew him only from his late tapestries and sculptures, with their bird motifs and fields of color, might mistake him for a sentimentalist. Here, he and painting come out fighting.

MoMA displays the decade as twelve discrete series. They may have run to as few as half dozen works apiece. One advantage of a show like this is seeing the survivors nearly complete. The online exhibition has most of the rest. They end in a work not in series, from the museum's permanent collection. Still Life with Shoe took him four months alone, and it marked a return to painting from life.

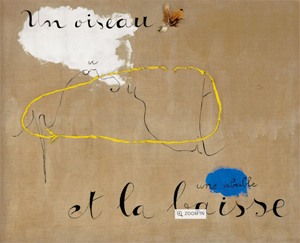

The series start with paintings on unprimed canvas. That means no coat of gesso or other primer to protect oil or the elements from eating right into the fabric. It means the color and texture of canvas enter the composition, as prominent as the concentrated spills of paint. It allows the canvas to function as a ground for spare lines or handwritten words in black water-based media. The medium really is the message—or many messages within a single painting.

Un oiseau (a bird) traces over a cloud of white, next to red feather itself like a paint spill. Below, une abeille (a bee) hoards a spot of blue. At the very bottom in larger letters, et la baisse (and lowers her or, vulgarly, screws her) may complete the sentence or pun on et le baiser (and the kiss). One might not even notice right off that poursuit (pursuit) snakes through their midst in scragglier letters. The word escapes a yellow open circle, and the letter u escapes even the word. Who needs painting, when its signs are everywhere?

In the final series, simple forms again appear on a fair degree of open space. Masonite here plays the role of canvas, and its rough and smooth sides alternately play its weave. Some smoky brown casein either heightens its textures or supplies depth and shadow. Oil color has barely expanded, to black, white, and the three primaries, but now black rather than white predominates. When two primitive profiles meet over a nest of pebbles on sand and white oil paint, they could be completing the ritual of pursuit from the show's very first painting.

Anti-anti-painting

The series in between resist so straightforward a trajectory. They veer between impatient exploration and abrupt reversals. Sometimes Miró manages both at once, a kind of anti-anti-painting.

At first he deepens the sparseness of the unprimed canvases, with the four surviving Spanish dancers. Yet their grounds range from white to blue to tawny paper and to the look of smoke. Collage extends the puns—especially puns on symmetry and defying gravity. In one, a stone hangs down, while in another a hatpin sticks up at center from a cork and feather. The roundness of the cork and the head of the pin make both of them difficult to recognize. Another composes the dancer from a long triangle drawn on sandpaper, the found image of a shoe to complete its base, and nothing to balance it all but a black tracing and a small, white dot of oil.

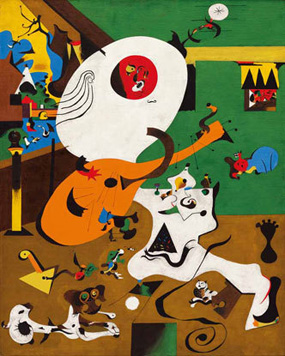

Dance continues next, but now in paint and in pursuit of the past. The head of a lute player, a tabletop, and a small riot take over a seventeenth-century Dutch interior, copied from a postcard. By 1929 painting has had its second chance, and Miró is back to a collage of found materials, wire, and other tracery. Next he divides attention between the poles of painting and anti-painting—as larger, more simply painted landscapes and heads vie with wood constructions. For once, he leaves some assemblies freestanding, but all more than slightly threatening. A bed of thick wire staples protrudes from one board, and tar paper forms the ground for another work.

Sure enough, painting roars right back, but this time based on collage. The Modern pairs each version, and the differences matter as much as the pairing. Collage originals pluck from magazines a machine's impersonality. Painterly form remains abstract and more schematic, but also freer, with rich, bright color brushed right onto the canvas. A series on the fabric-like surface of flocked paper attempts to reconcile the opposites next. Messy figurative drawing and pinup girls alike have a way of looking at once sensual and mechanical.

Again on flocked paper, pastels heighten the mixed message of good cheer and violent coercion. The clown heads in acid colors could be experiencing torture. A slightly busier series on cardboard includes the thick rope. A reptilian head looms above scorched earth. The one sculpture in the series mimics a dead stump. A turn again to paintings brings back the riot of imagery—or imagery of a riot—at the cost of the acid color of oil on copper.

Finally comes the series on Masonite, and the series are done. Miró is ready to paint again from life, assuming that he ever forgot life. He will survive till 1983. He will design a tapestry for the World Trade Center and die at the age of ninety. He will use those simple scrawls and open, soaked fields to recover a childlike faith in painting and his Spanish heritage. Some, at any rate, will exit confident in exactly that.

A long national nightmare

Others might come out a little less sure. The Modern tells a great story, helped by the artist, who tells dozens of them—but does it hold up? In this account, a Spanish expatriate experiences a crisis, while his homeland lies increasingly in crisis. Parisian art movements, which Miró refused to join, cannot satisfy him. Painting itself cannot. For a full ten years, he seeks to escape from the weight of fine art.

Wall labels relate the harsh technique to conditions back home. Collage references to the machine age, they argue, mean more than a critique of modern life. They reflect support for workers, against a backdrop of strikes and the rise of Fascism. As civil war unfolded and much of Europe looked the other way, Miró could not. Pablo Picasso felt it, displaying Guernica at an international exposition in 1937, but for Miró it made painting alternately irrelevant and imperative.

Wall labels relate the harsh technique to conditions back home. Collage references to the machine age, they argue, mean more than a critique of modern life. They reflect support for workers, against a backdrop of strikes and the rise of Fascism. As civil war unfolded and much of Europe looked the other way, Miró could not. Pablo Picasso felt it, displaying Guernica at an international exposition in 1937, but for Miró it made painting alternately irrelevant and imperative.

The rough textures and acid hues culminate in Still Life with Shoe. That one painting combines his running motifs of still life, landscape, and quotation from art history, one harsher than the next. The sickly, radioactive colors illuminate hills and plains without vegetation. The twisted tines of a fork stab into the spare meal, a single potato. The shoe has no mate (perhaps a jab at work boots by Vincent van Gogh), and even the bottle of alcohol looks skeletal and misshapen. Yet a decade has ended, and the Spaniard has rediscovered painting.

The story recaptures Miró's roughness, while covering most of his best work. Does his later art ever seem just plain childish? As a feminist's admission of sexism, I should say that I once assumed (seriously) that Joan named a woman. That is not at all to say that work this stern and compelling is masculine or that a woman could not have created its equal, but it is good.

The story also captures Miró's feeling for Spain. Its folk traditions did for his early art what night life did for Picasso. Born in 1893, he moved to Paris in 1920 but completed The Tilled Field in 1924. He was in Spain, in Cataluña, when general strikes broke out in Barcelona in 1934. He met his wife during that decade in Palma de Mallorca. When he hammered tacks into sandpaper, he could well have been hammering shut a coffin. Was it for painting or a free nation?

A story this good has to ring true, but I wonder. Is it a coincidence that painting recovers at the end, just as Modernism is about to find new life in America? The pocket history leaves out Miró's context in modern art. It isolates a period from some surprisingly similar work, and even that period's evolution mixes rebellion with patient exploration. Perhaps most of all, the isolation can hide the painter's relevance to current after current in art before and ever since.

Assassination as construction

Anti-painting has a history, too. One work's tilted paper rectangle could have come out of early Cubism, the rope out of Dada, the bacterial cilia out of Salvador Dalí, the spare collage assemblies out of Kurt Schwitters. Miró may never have joined the Surrealist circle, but he collaborated with Max Ernst. Even political disillusionment and war had taken their toll years before. Some have traced the Surrealist nightmare to the experience of World War I. Fernand Léger served at the front, where he lapped up weaponry as an emblem of modernity, but many others fared worse.

Still more evidence comes from the art. One can see continuities with art before and after, going back to the technique of oil on copper during Mannerism. Miró's spare but murky surfaces start with The Birth of the World in 1925, while the visible brushwork in a field of color appears that year as well, in Siesta or Bathing Woman. Motifs from the key ten years dominate his later, larger canvases and tapestries—the birds, the cilia, the fields of pure color. After color-field painting, that work should look like a summation.

The continuities stand out even more within his work, as with the touches of raw canvas. Miró does not proceed linearly from renunciation to another attempt at fine art and back again. One can almost always spot a transitional work between series—such as a collage curve that echoes the table in Dutch Interior. Even the wood assemblies run concurrently with a series of painting. Other echoes and quotations pop up after a longer separation. A white abstraction in the very first series, perhaps derived from a folk dancer's profile, reappears later as the bust and dress of a lady.

These strategies of stripping away and piling on reveal heretofore unseen surfaces and associations, while returning to old ones. Jacques Derrida called strategies like these erasure and the supplement, and he considered them both part of the production of meaning. Sandpaper, tacks, a draftsman's triangle, linoleum, and tar roofing look ugly and abrasive. However, they also define this as an art of construction, the reconstruction of painting from the ground up. It is a humble form of construction, another tribute to native traditions—but humility does not conflict with ambition.

One could be seeing quote after quote from other artists—not least from artists who came later. The saturated canvases based on collage anticipate Mark Rothko or Arshile Gorky, while the loose, watery black lines point toward Jackson Pollock and Pollock's Mural. A purple head in profile could pass for a Sigmar Polke. Mediterranean Landscape has soft-edged swirls of color like those of Helen Frankenthaler. Robert Rauschenberg could have exhibited at least one construction of burnt wood alongside his combine paintings, while clown torture looks ahead to Bruce Nauman, and Martin Puryear has most likely borrowed a ladder or two. If Miró stopped painting's clock for ten years, it still gets the time right at least twice every day.

What here counts as painting and what as anti-painting? Both found new relevance again and again not so very long ago, in postmodern pronouncements of the death of abstraction and the death of painting. Miró did wish to assassinate painting, but one can only assassinate someone feared and revered—a public figure and a leader. Assassinations start wars. They also allow someone to live on in ritual and memory. And he did as much as anyone to ensure that painting would as well.

"Joan Miró: Painting and Anti-Painting, 1927–1937" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 12, 2009. A related review looks at Miró in MoMA's collection and his "Dutch Interiors."