A Fiercer Piety

John Haberin New York City

Hans Memling: A Reunited Altarpiece

Martin Luther and Lucas Cranach

Do you always come back to Hans Memling in his old place at the Morgan Library? Maybe you loved the museum ever so much more as it was, before renovation and expansion. You entered then not through an atrium, but through a weighty door and domed rotunda.

Maybe you miss seeing J. P. Morgan's private library as the building's heart, with a selection of Renaissance paintings in his study. Maybe you first came to know Memling from the wings of an altarpiece there from around 1470, set around a painting from another hand and another country entirely.  Whatever your regrets, all is forgiven, for now the Morgan displays him just as he intended, with "Portraiture, Piety, and a Reunited Altarpiece." It also displays a far fiercer piety just fifty years later, with Lucas Cranach the Elder. He appears as a close friend and exponent of Martin Luther's Reformation.

Whatever your regrets, all is forgiven, for now the Morgan displays him just as he intended, with "Portraiture, Piety, and a Reunited Altarpiece." It also displays a far fiercer piety just fifty years later, with Lucas Cranach the Elder. He appears as a close friend and exponent of Martin Luther's Reformation.

If Memling's work merges piety and portraiture, what does that say about religious painting then or the spiritual in art ever since? What about Cranach's merger of piety and polemics? One can see Christian narratives as no more than a given for the Renaissance—or as part of a growing secularization of ever since. One can see, too, how the Reformation merged religion and politics. One can see as well how painters grew to a greater intimacy and parity with their patrons and subjects. And that in turn meant a growing shift from symbolism in painting and ritual in the church to a direct and individual encounter with both art and worship.

A gentle unity

When the Met sought to reconstruct a painting by Jan van Eyck, you knew to expect Christianity, art, and nature alike struck by lightning. You may remember Hans Memling as merely tasteful, like the Renzo Piano architecture. Yet his reunited altarpiece includes literal thunderclouds. Dark patches in an upper corner of each wing extend into the central panel, on loan from the Musei Civici in Vicenza, neatly framing Jesus on the cross. They appear because the heavens darkened at the moment of death, but also because this artist was out to unite a panel and its wings, religious painting and landscape, northern drawing and Italian sunlight in a measured symmetry.

The weather aside, the work packs a surprise by its very subject matter. You may remember the side panels as portraits, despite the attending saints, with good reason. Saint Anne and Saint William look more placid than superhuman, the first with her hand on her namesake's shoulder. Anna Willemzoon may need reassurance, for Memling treats her age unsparingly. Despite the age differences, too, you may think of the kneeling man and women as husband and wife. You may expect them, as donors, to frame a scene out of the Bible.

In reality, the donor kneels in prayer in the central panel, beside the cross and opposite Mary Magdalene, and the curve of her body responds to the forward thrust of his hands. Jan Crabbe, the abbot of a Cistercian monastery, kneels in front of his namesake, John the Baptist, but also the founder of his order, Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard dresses in white and holds a staff like Jan, while his aging face connects him to Anna. The side panels depict Crabbe's mother and brother, and their acts, too, register subtly in the poses of others. The distant landscape looks just as earthly in each panel, too. Memling imagines not a view from this world onto the next, but a union of both.

The back packs a surprise as well, with panels from the Groeningemuseum in Bruges. One would have seen them only when the altarpiece closed. Typical of his time, Memling uses them for an Annunciation in grisaille, or shades or white. In a church altar they would have echoed the surrounding carved stone, as an intermediary between architecture and painting, but also art and life. Here, though, Mary and the angel have fleshly hands and faces. The artist cannot resist bringing them that much further to life.

One may see him at his best in portraiture, as with a 2005 survey of Memling portraits at the Frick (when I already got in most of what I have to say). This small show includes three more portraits at that, including one from the Frick and one from the Morgan itself. Memling uses small strokes in one for individual hairs, animating a study in intellect and respect, while loosening his hand for beard stubble in the other. Another painting, by the Master of the Saint Ursula Legend, shows Saint Anne encompassing Mary and her son, closer to the artist's first thoughts, to judge from x-rays. Books of Hours and drawings trace the continued secular trend in art in the Northern Renaissance. Gerard David uses a sheet for eight different faces, from smiles to grimaces, as studies in types.

Memling left no preparatory drawings, and none appear beneath the side panels. He may have worked things out, however cautiously, on the spot. He lacks the tense outlines of his teacher, Rogier van der Weyden, or van Eyck's intricate symbolism and brushwork. In this early painting, from soon after Memling's arrival in Bruges, Mary swoons almost splat against the painting. He gained in skill, but he still wants to bring together the strengths of other artists, without their psychological or spiritual penetration. And yet that gentle unity was itself an innovation.

Spread the word

The Reformation had a lot going for it. I mean not doctrine, corruption in the Catholic Church, and a budding nationalism—but the pulpit, the Bible, and the printed word. So why not art? "Word and Image: Martin Luther's Reformation" puts painting at the very center of Luther's writing and influence, at the Morgan Library. So, too, at its center is a painter, Lucas Cranach the Elder. It displays their friendship as akin to a collaboration.

Martin Luther spoke for himself, published for himself, and translated the Bible into German. He took advantage of a revolution well beyond the Church, in movable type. And he and Lucas Cranach did collaborate, on a book with words by one and illustrations by the other. He was not, though, determinedly high tech. He first nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to a church door in defiance in 1517 (or at least hung them from the door to welcome debate, depending on which historian weighs in), before they became a broadsheet, like a modern newspaper, and a quarto—a smaller format akin to today's paperbacks. He also wrote hymns and urged schools to teach music.

Painting, then, seems only natural. It had worked on behalf of church and state for as long as either existed, and it would do so again. Images are pliable, too, even at their most dogmatic. Albrecht Dürer, himself a proponent of reform, created an engraving of Saint Jerome in his study in 1514. In the hands of others, that became Luther in his study. In more ways than one, artists were crafting an image.

But did Luther want one? Plenty of reformers did not, in response to what they saw as Catholic idol worship and the Bible's forbidden graven images. They had their public burnings of books and art, not to mention of people. Luther, though, saw an opportunity —zum Ansehen, zum Zeugnis, zum Gedächtnis, zum Zeichen ("for recognition, for witness, for commemoration, for a sign"). He also saw a friend in Cranach, ten years older and painter to the electors of Saxony. Luther acted as godfather to Cranach's son, and at Luther's wedding Cranach gave away the bride.

—zum Ansehen, zum Zeugnis, zum Gedächtnis, zum Zeichen ("for recognition, for witness, for commemoration, for a sign"). He also saw a friend in Cranach, ten years older and painter to the electors of Saxony. Luther acted as godfather to Cranach's son, and at Luther's wedding Cranach gave away the bride.

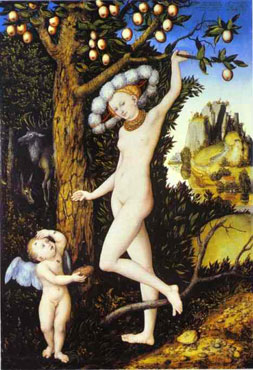

The show's literal center, a six-sided chamber homes in on the painter. Courtly and decorative, he could give myths a playful, sexual twist—or close in to make eye contact with Jesus. Influenced by Dürer and the Danube school of the Northern Renaissance, he could also set his scenes against preposterously tall blue mountains and a touch of Italian light. His portraits run to jagged outlines for jaws and cheeks, set against plain backgrounds, with a gentler modeling to add warmth, flesh tones, and a third dimension. They include at least two paired portraits of Luther and his wife. If Cranach's output looks uneven at best, he also had one of the largest workshops in Europe, ideal for getting the word out.

He does not make a huge fuss about it, even when he stays on message. That eye contact, in a painting of Jesus together with Mary, carries Protestantism's pledge of salvation through faith, without an intermediary in the pope's legions. Adam and Eve serve a new elevation of marriage, now as a matter for church approval rather than private vows. Earlier, in 1520, a portrait of the young Luther as Augustinian monk was one of several, for Luther's several roles as teacher and reformer. Mostly, though, Cranach just carries on with his gentle tease. The Reformation may even have let loose his sensual side, as part of a greater individualism.

All that adds up to insights, but also to lost opportunities. The curator, John T. McQuillen, could have shown all of Luther's early roles, as the equivalent of a contemporary graphic novel. A painting of Luther and Cranach together, from the 1550s, does not appear at all. They stand at the base of the cross, beside John the Baptist, with blood from Jesus spurting right onto their heads. In the end, this is Luther's show, but as word and image—much like the Morgan's recent show of photographs as "Sight Reading." Long before text art, an image could spread the word.

A reunited altarpiece by Hans Memling ran at The Morgan Library through January 8, 2017, Martin Luther's Reformation through January 22. Related reviews look at Memling portraits and an Italian influence on Lucas Cranach.