Texting the Stars

John Haberin New York City

Sight Reading, Michelle Stuart, and Mark Lyon

In 1966, the year of Revolver, the Beatles sat for publicity photos—of only their lips. Their familiar faces might pass unrecognized without a hint, their familiar voices reduced to silence. More than thirty-five years later, Jonathan Lewis closed in instead on their record covers, pixilated beyond recognition. Just as vinyl was making a comeback, they entered the digital age as little more than colored squares.

So which photographs count as art for art's sake, and which are sending a message? If you hesitate to say, you can find both sets at the center of "Sight Reading: Photography and the Legible World," at the Morgan Library.  Meanwhile Michelle Stuart in her own way, in photographs and earthworks in the Bronx, is reaching for the stars, and Mark Lyon finds the most elemental signs of nature in a car wash. Still cannot decide? Still unsure when repetition of a familiar image turns it into text? Read my lips.

Meanwhile Michelle Stuart in her own way, in photographs and earthworks in the Bronx, is reaching for the stars, and Mark Lyon finds the most elemental signs of nature in a car wash. Still cannot decide? Still unsure when repetition of a familiar image turns it into text? Read my lips.

Show and tell

Not one of the Fab Four could sight read in music, but photography, the Morgan argues, entails reading as well as sight. It is about telling as well as showing, and it is concerned with gathering signs and sending a message. In the case of the Beatles, the publicity stills (by Jean-Pierre Ducatez, a French photographer) project the growing interiority and experimentation of four very public figures. They belong to the Morgan, while the second set belongs to the George Eastman Museum, which supplies much of the show. It comes after decades of critical talk of art as text, text as art, and line as language. It includes science and advertising alongside museum photography going back to the very origins of the medium, and it dares one to say which is which.

Does its own text message hold up? The curators, Lisa Hostetler of the Eastman Museum and the Morgan's Joel Smith, quote László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus, who wrote that literacy would soon demand "the use of the camera as well as the pen"—but then Modernism back then was big on utopian futures. And his own contribution from 1927, a photo collage of nudes as Massenpsychose (or "mass psychosis") is all about silencing the voice of madness. The show speaks of photography as "writing with light" in a "range of dialects," but that alone implies a common language. In practice, its many voices and languages add up to a welcome cacophony. You can write your own story.

Nominal divisions bear such titles as "The Camera Takes Stock" and "Crafting a Message" that are hard to tell apart, much less apply. Lewis W. Hine was crafting a message as he went through prints of his Powerhouse Mechanic, a laborer fitting so neatly into a steam pump that he becomes its driving engine—and that of capitalism as well. Yet Hine was also crafting a message as he cropped immigrants to America, on quite another wall, not far from the witty political photography and photomontage of John Heartfield. Meanwhile that earlier section also includes Sophie Calle, who combined text and photographs while working as a hotel chambermaid in 1981. "I hear them shouting," she writes, a couple has "only coffee" for breakfast, and "the left pillow is stained." Her narrative appeals not just to legible signs but to all the senses, and its messages could belong to others or to her.

Many of the show's most telling pairings occur across sections—or within a single image. On another wall, Duane Michals, too, adds handwritten confessions to shadowy photographs, for The Man in the Room. The man was dead, he pleads, and "yet here he was!" Michals looks into a mirror, as if to silence his fears, but "I could not see myself." Separate walls also hold Richard Sharpe Shaver's glistening Rock Prints and a scientist's sandstone. Robert Adamson titled his portrait in a churchyard The Artist and the Gravedigger. But then Hine spoke as not just a photographer and social reformer, but also a trained sociologist.

Photography here appears less as a sign system than as a compendium of existing signs. It runs from book covers and log books to color charts, marriage certificates, fossils, studies of human physiognomy, "PhotoMetric tailoring," and more than one biologist's photomicrographs. It details the surface of a dried lake and the surface of the moon. It includes President Grant from an unknown photographer on his way to the dollar bill. John Baldessari fashions smoke into the words "Seeing Is Believing," for his Cigar Dreams. An artful compendium of cities reaches from sidewalks to storefronts by Eugène Atget, Andreas Feininger, Margaret Bourke-White, Aaron Siskind, and others, as the "Empire of Signs." It could well have included Bernd and Hilla Becher from quite a different section—or Paul Strand and Irving Penn at that.

Among its narratives, the show also displays the medium's reflections on itself. It opens with William Henry Fox Talbot wondering whether his photograph of a china collection could stand in for the objects were they destroyed. It juxtaposes motion studies by Eadweard Muybridge, Harold Edgerton, and Etienne-Jules Marey to contrast the techniques of multiple cameras and multiple exposures. It has John Pfahl measuring out waves breaking on the coast of Hawaii. It follows Robert Cumming onto a set at Universal Studios. Maybe photography is not science after all, and a message is not always art.

The works of man

It takes a certain arrogance to compete with the processes of nature. It may take even more to compete with the works of man. Do excuse me if I use an old-fashioned, not to mention sexist term just this once. Michelle Stuart sets her sights on storied monuments and civilizations. When she creates earthworks, she sets her sights high in fully her own voice—and when she translates her art into photographs, ancient and modern share the walls without a break. If the Bronx Museum did not occupy the Grand Concourse, she might have to transplant it for the occasion.

As a woman, Stuart is quite happy to compete with the works of man on their own terms—and to claim them as her own. She has been presenting art as a force of nature for decades, but with a very human twist. Some years ago, a show of feminism and land art presented her and others as doing just that. Did men like Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson pile on bulldozer after bulldozer's worth of earth? Did they anticipate the macho of Mike Bouchet with his urban excavation or Tom Sachs with his pretend space program? Women, SculptureCenter argued, had to leave defter and more deceptive traces, as "decoys, complexes, and triggers."

They could think in organic rather than geologic time, like Agnes Denes with her Wheatfield in Manhattan or garden pyramid in Queens. They could leave charred remains and sunken chambers. Come to think of it, with his Monuments to Passaic and dedication to entropy, Smithson was reasonably modest all along. Yet even there, Stuart was different—on a cosmic scale. She created star charts, and she used graphite and earth all but interchangeably on canvas. Her Stone Alignments, Solstice Cairns, set by the Columbia River in 1979, implicitly evokes Stonehenge itself.

They could think in organic rather than geologic time, like Agnes Denes with her Wheatfield in Manhattan or garden pyramid in Queens. They could leave charred remains and sunken chambers. Come to think of it, with his Monuments to Passaic and dedication to entropy, Smithson was reasonably modest all along. Yet even there, Stuart was different—on a cosmic scale. She created star charts, and she used graphite and earth all but interchangeably on canvas. Her Stone Alignments, Solstice Cairns, set by the Columbia River in 1979, implicitly evokes Stonehenge itself.

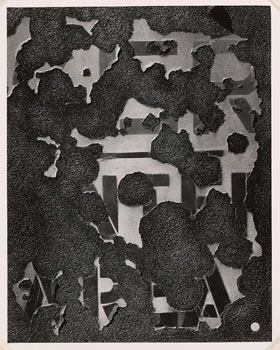

"Theater of Memory" in the Bronx takes off from her Codex series, squares of earth-rubbed paper from the early 1980s. Already she was ranging widely in cultures and in time, with earth from a New Jersey quarry and a Mayan city. It also includes a tray of samples, like an archaeological dig. Around this, though, she adds twelve large grids of photographs of varying dimensions, only partly to document the older work's origins. They become scrapbooks of personal and archival photographs alike. In calling the new work My Still Life, she places herself first.

Each grid functions as a series to itself with a distinct time and place. They include the New Jersey quarry and a solstice in Machu Picchu, but also a night in Paris. They present alternative modes of representing humankind and nature as well, including celestial landscapes and nineteenth-century science. They look to higher powers, like a cat god or goddess. They also never quite get over an old-fashioned sense of "the primitive," including native girls, as something finer. Black skulls and a mushroom cloud ought to know better, but do not count on it.

Now in her eighties, Stuart is never fully at home in the present, assuming she ever was. Paris here is a city of carousels and antique watches, and she calls one series Time Recaptured. Sepia-toned shells, ferns, beaches, and butterflies bring the sole note of color. She does, though, leave a pageant of traces, from sunlight in Peru to the archaeology of New Zealand and Australia. Human silhouettes weave among bubbling springs, eclipses of the sun, and phases of the moon. Now if only she had room for Yankee Stadium.

Along for the ride

For a child, a car wash is the equivalent of an amusement park ride without the fear. It makes sense that your parents take you to both. In each, the vehicle moves passively forward, with a splash of soap as fragile, white, and entertaining as a ghost. For Mark Lyon, the ghosts are real, but not the ride. For him a car wash is a window onto a wider world. It holds a refuge from the ice and cold.

That wider world is the greater New York area, but one would hardly know it. These are not the car washes that serve as a treat for a child. Employees do the dirty work without automated assistance. While one interior has hoses on facing walls, others lie empty of anything. Who knew that a car wash has such affinities with Modernism's white cube? Who knew, too, that it holds such deep vistas onto a greener nature?

In each, the back wall frames the open garage door, with a distant vision in green or white. Confining walls converge rapidly onto depth. Some look out on post-industrial trappings covered in snow, another on an additional pump in bright sunshine, like a doubling or displacement. Others offer a lusher view, beyond the promise of suburbia. Lyon insists on symmetry, with no others in sight. Where would they belong?

The camera, needless to say, has a long love affair with perspective, going back at least to Soviet photography, and with America by car. Yet nothing links these photos to a past generation more than their deliberate banality. The subject resembles gas stations, in paintings by Ed Ruscha, while the photographs in series recall Ruscha's Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Smithson was just as breathless about New Jersey with his Monuments to Passaic, and the view down interiors with stories to tell has affinities with subway cars for Duane Michals and Danny Lyon as well. These photos differ in the opening, but also in their lack of narrative. One cannot imagine adding text.

One knows the confining geometry from Minimalism and the doubling from René Magritte. What, Lyon seems to say, could be more minimal or surreal than suburbia? Suburbia appears in photography these days more as theater, as for Gregory Crewdson. Lyon turns down the volume once again. An amusement park ride is out of the question. Still, his vision of everyone's backyard as a greater nature connects to Crewdson and to a related tradition in American art as well, what a show of Frederic Edwin Church called "the promised land."

Lyon brings that vision to the ordinary without quite debunking it. In one photo, it becomes intimate enough to evoke a Chinese landscape and its "Companions in Solitude" as much as New York and New Jersey. Trees encroach on the interior, making it another green world. The right wall holds the silhouettes of more, overflowing obvious boundaries. Are they the far side of a glass wall or shadows cast from the open door? Enjoy the ride.

"Sight Reading" ran at The Morgan Library through May 30, 2016, Michelle Stuart at the Bronx Museum through June 26, and Mark Lyon at Elizabeth Houston through June 12. The review of Lyon first appeared in New York Photo Review.