Fear and Loathing in Modern Art

John Haberin New York City

Egon Schiele in the Leopold Collection

Schiele's Living Landscapes

Can the "shock art" of Postmodernism have a point of origin in Modernism itself? The Museum of Modern Art places it in Austria, the country of Schoenberg and Wittgenstein—and the country of Egon Schiele. And then the Neue Galerie singles out his sense of place in "Living Landscapes."

Conventional shocks

The terrors of Expressionism might be inseparable from modern art and, for Fascism, "degenerate art." Yet the movement was conventional to its core in ways that the Nazis overlooked. To see something as offensive, one must see it first as a distortion, a violation of norms that refuse to go away. Other artists in those critical years before World War I preferred to move the norms. The old norms remain explicit, but as something cast aside. They are something from which art provides liberation.

When Robert Delaunay paints the Eiffel Tower, one can see it not as realistic, but as crumbling apart. When Chaim Soutine a side of beef or volcanic landscape, one can see it taking flight. Kandinsky makes the same move on his way from landscape to abstraction. German and Austrian Expressionists, too, return to the repressed, even as they wear on their sleeve all the old world's layers of guilt and repression. They want to offend and to suffer simultaneously. The combination is also why Oskar Kokoschka, an Austrian, could create such fine political posters.

I admit all that because I learned it anew from a surprisingly fresh and intriguing show. It contains about thirty paintings by Egon Schiele and well over one hundred drawings. They are all from one source, the Leopold collection in Vienna. Given the artist's early death, that amounts to a reasonable retrospective. With a second show years later at the Neue Galerie, one can call that retrospective complete. If its collective picture is at all distorted, this is, after all, a master of distortion.

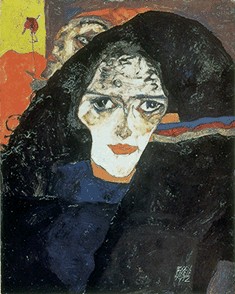

Schiele's work can look like nude centerfolds for a journal of sexually transmitted disorders. It comes in a long train of art that wore its emotions on its sleeve, from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. Think of the trail from Sandro Botticelli, Hugo van der Goes, and Vincent van Gogh to Arshile Gorky. Yet Schiele's suffering can seem to come out of nowhere, while his anger is fixed determinedly in past art. For all my doubts, that is a potent combination. Art this hung-up presupposes enormous skill and radical implications.

Schiele suggests that the necessary first step in offending others is to offend oneself. A genuinely shocking art cannot afford arrogance. Jeff Koons in New York today or the Chapman brothers in England may be smug, but they really want their audience to grin like insiders. Schiele wanted to shock. Only a nightmare could express his hatred of bourgeois Austria and his loving perception of nature's melancholy. The combination adds up to a fascination with self-loathing.

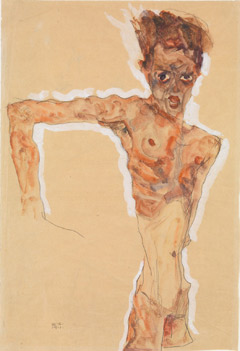

He may appear to experience revulsion at the human body, but revulsion implies a turning away. His ego is too strong for that and, perversely enough, too healthy. He is also too detached an observer. The many self-portraits are horrifying, but they never intend a withering self-examination. Nudity never precludes playing a part. It may or may not be the part of the artist.

Saints, sinners, and lovers

He and his future wife appear again and again as saints, sinners, or lovers. They can be superhuman sufferers or bare flesh. In his rapid sketches before a mirror, he adopts poses that seem to leave no room for him to observe and to hold a brush. His pen or palette is never on view. Only the decorative veneer of Expressionism reminds one that he is locked into a game of fine art. He might be waiting on you to make the first move.

Besides revealing so much of Schiele's complex attitude, MoMA also makes clear that he could draw. His mentor, Gustave Klimt, nurtured his economical draftsmanship. He learned quickly. A human outline is reduced to just a few lines, shading to a bare touch. When he is not exposing his or his model's crotch, drapery makes an eerie synecdoche for private parts. And it works.

I also saw a side of Schiele new to me, stark landscapes of 1912. A tree intertwines with an autumnal sky that could almost be a rock face. A shed in dark green and brown plummets into three dimensions. It dares the artist to continue Klimt's flattening of depth. It dares him, too, to continue shocking himself. And then he hid himself entirely in landscape.

I also saw a side of Schiele new to me, stark landscapes of 1912. A tree intertwines with an autumnal sky that could almost be a rock face. A shed in dark green and brown plummets into three dimensions. It dares the artist to continue Klimt's flattening of depth. It dares him, too, to continue shocking himself. And then he hid himself entirely in landscape.

A second show takes takes his landscapes seriously. Can it preserve the shock? Schiele grew up in the shadow of sex and death, but it took him until he turned twenty to make them the stuff of his art. He hardly changed for the rest of his life. He had little choice, for he never reached age thirty. Besides, sex and death kept him busy enough along the way.

His father died of syphilis, and his parents suspected him and his sister of playing around. He formed relationships on his own terms and expected an open marriage. When that failed, he and his wife left Vienna for a town where their house became a haven for teenage girls. Arrested for seduction, he could have spent the rest of his life in prison, but the authorities settled for a charge of possession of pornography—more than a hundred drawings from his own hand. He walked free just in time for conscription in World War I. He died of the flu epidemic in 1918.

You may remember him for a painting of Death and the Maiden. Suffice it to say that they are in bed together, and the Schubert string quartet goes unheard. You may remember him that much more for obsessive self-portraits, often nude. Gaunt arms and hands extend to frightening proportions, their joints red with pain and the little flesh that remains touched by a gangrenous green. The Neue Galerie, though, sees his move from the big city as a return to a more idyllic childhood. It sees landscape painting and drawing as the one constant in his art, "Living Landscapes," through January 13.

The shadow of death

The Neue Galerie includes photos of Schiele and poems expressing his dark, conflicted relationship with earth and sky. In reality, he was a handsome, charismatic young man, although always brooding. On coming to Vienna, he sought support from Klimt and Kokoschka, and he got it. He exhibited with the first wave of Austrian Expressionism, the Vienna Succession, in 1909. Administrative duties in World War I kept him from painting, but also from combat, and he continued to exhibit widely, in Vienna, Paris, and Berlin. If he had settled outside Austria's legal and cultural capital, no one more relished the pose of the outsider in art or life.

A room for his early years does not look all that promising. Had Schiele died in 1910, like Paula Modersohn-Becker three years before, he might be remembered today as a Symbolist or not at all. When he paints landscape as a teen, it has little to do with nature. Dark compositions flecked by light look like nothing so much as Le Moulin de la Galette, from Pablo Picasso in 1900, when he, too, was anything but revolutionary. Schiele himself might have wondered if he would ever lighten up. Fortunately, he rediscovered sex and death.

For the 1909 Vienna art show, he contributed a painting of Danaë—smushed to the ground, but still a bloated white. Zeus came to her in a golden shower, but Schiele cuts out the gold and the rejuvenating rain. Soon enough, too, he introduces men. Lovers share a bed, seen from above or from nowhere at all, their long limbs at impossible angles. When he works on paper, the ground is as stained as the bodies. All he lacks is the gangrene, and that, too, is on its way.

Just months ago, the museum boasted of Klimt landscapes, but the show delivered far more than it promised. So does this one. A central room has landscapes to either side of the mantel, but with a visitor's back to them coming in. Check out one, though, and its trees cast their branches everywhere—continuing as cracks in the soil, like a self-portrait with cracked skin. On paper, a thin, bare tree bears a spot of red, much like the artist's knuckles. Could landscape have played a central role after all?

The last room follows him to the towns where he moved, and there, too, he has mixed feelings about the land. He lingers over a medieval town with its houses and spires, but with nowhere for him to stand, to observe, or to live. Distant hills have the angled blue facets of an iceberg. The town itself becomes a confusion of colors and geometries. And that confusion continues into paintings of a steel bridge and an equally massive mill. This may be landscape, but, yes, a living landscape, a place for the stubborn desires of modern life.

More than once, he returns to sunflowers. Had he developed a fondness for Vincent van Gogh and the gentle light of southern France? Yes again, and he admired van Gogh no end at an exhibition in Vienna. Still, he sticks to muter colors, and a rising or setting moon looms on the horizon like a distant eye. But then van Gogh, too, had his private terrors. And Schiele's flowers, unlike those in a still life, are rooted in the earth as he could never be in art or in life.

"Egon Schiele: The Leopold Collection, Vienna" ran through April 20, 1998, at The Museum of Modern Art. Related reviews turn to Schiele self-portraits and Schiele nudes.