The Tropics of Soho

John Haberin New York City

Mark Dion: Exploratory Works

Future Retrieval and Eugen Gabritschevsky

The Met has the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas and the American Museum of Natural History its special collections. Only the Drawing Center, though, has a department of tropical research. Future Retrieval and Eugen Gabritschevsky might be envious.

The first, a very small artist collective, creates its own museum of natural history on the Lower East Side—in a space barely big enough for a single diorama. It does, though, manage to draw in Rococo porcelain along with Asian and American landscapes. The few animals on hand may well belong more to the decorative arts than to nature. Do they bring natural history to the point of madness? Gabritschevsky does, and in 1926, then at the very peak of his career, he reported on "Experiments in Color Changes and Gender." He was not yet describing his art.

Tyger, tyger

Can the Drawing Center make room for a department of tropical research? At least it can for a few months, and its exhibition is an act of the imagination, but the department and the research are real. William Beebe directed it for over thirty years, on behalf of the New York Zoological Society—now the Wildlife Conservation Society. As the Center puts it, he "took the lab into the jungle, rather than the jungle to the lab." And now, more than fifty years after his death, he has taken it to Soho. It has taken in some artifice by Mark Dion along the way.

"Exploratory Works" lays out its history, with maps, documents, and period equipment. As curators, Dion, Katherine McLeod, and Madeleine Thompson bring these and more together in a tall cabinet and a recreation of its field station. They include a film of the research team poised to take their floating laboratory to the rivers and sea—in a bathysphere and along the coast of South America. Most of all, they set out the product of its research, in the form of watercolors of tropical life. The show gains relevance today thanks to global warming and Donald J. Trump, as scientists march for their and the planet's future. It has added punch, too, because women did so much of the drawing.

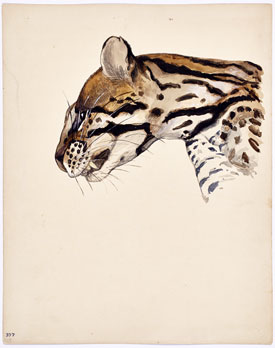

Some of the names are lost, including both artists and species, but Isabel Cooper helped get things moving when she joined Beebe in 1919. They show the world less as "dog eat dog" than as animal life struts its stuff. A tiger for Cooper, as for William Blake, is burning bright, while ocean sunfish for Else Bostelmann appear to smile or to cower—even as a viper fish swoops in with its saber-toothed jaws. The stomach contents of another deep-sea fish, notoriously larger than the fish itself at rest, seem to be getting along just fine. Plants or invertebrates make an appearance only as a backdrop to the exotic display of color and motion. An insect for George Swanson Carpito may be feeding on a leaf, but the leaf seems to be deepening its pink and purple on behalf of the bug.

Then, too, there is another element of their symbiosis and the ecosystem, in Dion. The field station looks more convincing than many of the drawings, but he has pretty much made it up. It has a full wall where one can linger but not enter. It also has the clutter and quaintness of his Curiosity Shop, again at the intersection of art and science. Like Beebe, he has made art from the space between sea and shore, with his Thames Dig, and has gone deep with his Rescue Archaeology. He has to like a project in which the same individuals served as lead scientists and field artists.

The entire exhibition may have one wondering what counts as science or art. Is the Drawing Center taking on the job of a natural history museum for a change? And is it doing so because that, too, is an aspect of drawing—or because the drawings are so vivid as art? (Cooper took pride in her Japanese brushes and spoke of a "tapestried" lizard.) Or is it doing so because they have become part of an installation by a living artist? One may wonder whether watercolors can do the job of science at all.

Of course, Beebe could not rely on color photography back then, especially in the field. And scientific drawings have a long history, including Leonardo when he had given up painting and Albrecht Dürer when he saw his work as art. Art and science, I have argued, can meet in more than one way. Art can take science as its subject, as with science fiction, or as the tools of its trade, as with color charts, color wheels, and Post-Impressionism. It can aspire to the study of nature, like science, or explore science as itself a mode of representation. The best side of "Exploratory Works" lies, like its title, in the plural.

Unnatural history

It takes a big imagination to recreate a museum of natural history in a storefront gallery. Barring that, one might have to settle for eclectic interests and a healthy skepticism. Under the guise of Future Retrieval, Guy Michael Davis and Katie Parker may not produce a museum. Yet they should have one pondering what they leave out. Their adopted name promises a time capsule, but for an age of data retrieval as automatic and impersonal as a museum Web site. Is the future already present?

For once, one cannot look for an answer from the street. A wood frame supports a curved wall barring views through the window. That seems only right. For a native New Yorker like me, the American Museum of Natural History holds not sunlit habitats, but darkened rooms and the chambers of memory. Inside, things are bright enough—like the white cube of a proper art gallery or museum. It should be more than bright enough to dispel childish misconceptions.

The curved wall holds a diorama between design and nature, but pretty much free of people or natural histories. It looks like a single scene, but with sudden discontinuities in content and color. Never mind, though, because the missing specimens stand on pedestals, including a wild bobcat and a rhesus monkey. Not that they make sense side by side either. The diorama has elements of the American west and old Europe, as if the Hudson River School and Nicolas Poussin in Rome were fighting over property and antiquities. The animals belong only to art.

For one thing, they are not stuffed but ceramic. In fact, a patterning more typical of Chinoiserie and glazed porcelain covers the bobcat. They also seem to have stepped right out of the domesticated wilds of a Rococo garden for Jean Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher. A finch on another pedestal is drinking from an urn more appropriate to a period room at the Frick. Then again, the diorama has the neutral background typical of a Chinese landscape and its "Companions in Solitude," but with no room for calligraphy or weather. It, too, is a product of information retrieval.

The artists are engaged both in sampling and erasure. They bill themselves as ceramicists, but the ceramics end there. Other vases appear on the facing walls, Rococo decoration intact, but solely in cut paper. The diorama is cut paper, too. As with Walton Ford, the wild animals could have stepped out of either or neither one. The whole display seems waiting for a museum curator to fill in the gaps.

The artists also boast of their care in sampling and reconstructing species from an actual natural history museum. That may sound odd, given that old ceramics and old museums alike took real work, with the digital as a suspect shortcut. As one exits, the wood frame seems more like a deconstruction of the scene within, and a few more urns sit on the floor beside it, but in wood. Rather than science or the imagination, they offer the lesser solace of a sense of humor. Has art lost access to the objectivity of a mirror of nature along with the fabled originality of the avant-garde? There may be limits even to future retrieval.

Experimenting on himself

When Eugen Gabritschevsky wrote about color and gender, he was a biologist, like a Czech artist, Anna Zemánková, with a specialty in insects. (That 1926 paper was about spiders, although Catherine Chalmers prefers ants.) The son of a bacteriologist, he had grown up in the most elite and progressive circles of tsarist and revolutionary Russia, at home among scientists, diplomats, and Tolstoy.  Fluent in English, he had just wrapped up his postdoc at Columbia University under T. H. Morgan, the leading geneticist of his age, and was settling into a post in Paris. In only five more years, he had lost it all to mental illness—but his greatest experiments were just beginning. For the American Folk Art Museum, he spent the rest of his life in a "Theater of the Imperceptible."

Fluent in English, he had just wrapped up his postdoc at Columbia University under T. H. Morgan, the leading geneticist of his age, and was settling into a post in Paris. In only five more years, he had lost it all to mental illness—but his greatest experiments were just beginning. For the American Folk Art Museum, he spent the rest of his life in a "Theater of the Imperceptible."

Insects live fast and die young. Not him. Sent to an asylum in Germany in 1931, Gabritschevsky was only slowly picking up the pieces and discovering his art. Some of it still looks like scientific illustration, including exquisite bird studies in his chosen medium, gouache on paper. Folding and blotting brings out the symmetry and segmentation of, once again, insects—if not also a Rorschach test. The show's title brings out the parallels between his lives. He was making the imperceptible visible, just as he had behind a microscope.

Increasingly, the imperceptible belongs not to the furthest reaches of the senses, but to the mind. In his art and madness, like Joseph E. Yoakum, he can experiment only on himself. The birds morph into faces, their color and gender no longer intact. Forms multiply, with the obsessiveness of folk art and outsider art—and who is to say what is glorious and what is a nightmare? Memories of Moscow before the revolution become images of crowded theaters, but of solely the audience in fancy dress and with mere dots for eyes. Gabritschevsky's subject has become the pageant not of art and nature, but of the perceiver.

He might have seen the changes coming as early as his stay in New York. A crowded skyline in charcoal has one foot in science fiction, with seemingly familiar towers rising a good five years before construction of the Chrysler building began. A man leans over his microscope in the laboratory, but in near darkness. Seen from the back, he is and is not the artist. Then, too, the move from hard science was never quite complete. Species other than people join the lost souls at the Last Judgment, and men with odd growth for heads could be suffering from a physical as well as mental disease.

Those crusty heads look right out of Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut, and Gabritschevsky's brother wrote for encouragement. The French painter was polite but measured. Gabritschevsky, he explained, was not turning against "l'art classique" but rather "handling" it. He had done so before in charcoal, with those skyscrapers informed by Modernism—or with a ghostly man in the woods informed by Symbolism and Edvard Munch. The Last Judgment, too, is a classical subject, rendered in lush browns. Yet its god is only a small point of light, and its tiers belong just as much to the artist's theaters of Moscow and the mind.

Maybe Gabritschevsky never had time to become an outsider or an artist, as his state of mind grew worse. Work belongs almost entirely to the 1940s, although he died only in his mid-eighties, in 1974. The museum pairs him with Carlo Zinelli, an Italian who took up art in an asylum well into his forties. Zinelli had served both in a slaughterhouse and (by devilish coincidence) in combat, he exhibited with Art Brut, and his work became more cramped, chaotic, and colorful right up to his death. Gabritschevsky, by comparison, was at least half in control of his experiments all along. They just had a way of turning on him.

"Exploratory Works" ran at the Drawing Center through July 16, 2017, Future Retrieval at Denny through November 12, and Eugen Gabritschevsky and Carlo Zinelli at the American Folk Art Museum through August 20. Related articles take up the themes of art and science, natural histories, art and ecosystems, and Art Brut, with Mark Dion and others.