Science Fact and Fiction

John Haberin New York City

Useless and Mundos Alternos

"All art is quite useless." Maybe so, to quote Oscar Wilde, but is it all quite "Useless"?

A show of just that singles out just seventeen artists with, in its subtitle, "Machines for Dreaming, Thinking, and Seeing." Were their machines, found or constructed, not useless enough, they are happy to cripple or dismantle them. They could do with a little more dreaming and a lot more thinking and seeing. They do, though, raise the question of what counts as quite art or quite useless. So does a show that claims another kind of dreaming as a path to cultural identity. "Mundos Alternos" celebrates art of the Americas as science fiction, but that central fiction cannot count as fact.

Uses of enchantment

Wilde wrote his preface to The Importance of Being Earnest at a turning point for art. As the nineteenth century ground to an end, it had outgrown the academies and patrons with demands to glorify themselves or their nation. He anticipates Modernism's formal purity, but stops short of its promise to transform society, as with Soviet art and the Bauhaus, or to lay bare its dark unconscious, as with German Expressionism and Surrealism. Wilde himself could feel exuberant or fatally trapped, and that fin de siècle ennui has to resonate with the ragged state of art today. Maybe art now is more wrapped up in identity politics and affirmation, like "Mundos Alternos" or the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Still, then or now, is uselessness a rebellion against "capitalist society, which has been criticized for its lack of moral and spiritual values"?

So, at least, argues the Bronx Museum. And that suggests a tension at the heart of "Useless." Does it aspire to be it truly useless—or what Bruno Bettelheim, in speaking of fairy tales, called the uses of enchantment? The curator, Gerardo Mosquera, also cites Aristotle on knowledge as valuable in itself. That sounds much like art for art's sake, but the artists themselves might not agree. When José Iraola turns his broken camera on The Mona Lisa, distorting its colors and stretching its smile to the breaking point, he displays a gleefully ambiguous trust or distrust in art.

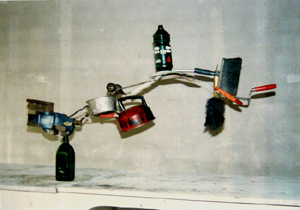

Adriana Salazar introduces herself and the assembly with Careless Machines, with an obvious pun on careless. Two fragile poles, like mike stands, hold shot glasses, like a party for two. Soon enough, Arnaldo Morales, Chico MacMurtrie, Johanna Unzueta, and Shih-Chieh Huang join the celebration with whirling tentacles, robotic cushions, felt on wood spools, and self-inflating limbs akin to wings. Are we having fun yet? For the most part, yes, without probing very hard or deep. William Kentridge, to my surprise, had his own small Kinetic Machines in wood, but then his better-known videos make a point of their awkward assemblage frame by frame.

This is not quite new media, and it can seem alarmingly quaint. It includes machines as art and, with Roxy Paine, a machine for making art. Yet Paine's blobs of layered polyethylene already look like a failed attempt at 3D printing. Stefana McClure makes her works on paper by typing poetry, but with typewriter balls on each finger. (Remember that technology?) Simón Vega supplements a fallen Mercury space capsule with house plants to bring new life to the space program. A Telefunken radio from Jairo Alfonso would be comfortingly old-fashioned even were it not broadcasting news of crises from the 1960s.

They accord with bad boys like Mike Kelley and their "trash art." That itself can feel old, although all but one work in the Bronx dates from the new millennium. It also suggests another tension at a time of rediscovering women, in that those who show off by tinkering with machines lean to men—especially when they are trashing them. Wim Delvoye conceives his suitcase as a traveling cloaca, like an infant playing with its you know what. Shyu Ruey-Shiann fashions his Dreambox by covering its four walls with a disassembled motorcycle. One has to assume that the bike got plenty of loud use.

At least he is still dreaming. So is Juan Downey, whose architectural plans channel both clean and "invisible" energy. So, too, is Fernando Sánchez Castillo, whose robots designed to deactivate explosives take up painting. Algis Griskevicius recalls Leonardo's notebooks with photographs of The Dream to Fly and, well, The First Lithuanian Astronaut. They have their ancestor in Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Their 1987 video unfolds with a patience close to slow motion, like a waking dream.

The Way Things Go still amazes, enough to justify the show in itself. Useless is as useless does, and here it is modest in its uses but immodest in their execution. Like Ruey-Shiann, it turns destruction into the act of creation. One can hold one's breath as each rolling tire, slow burn, or chemical explosion triggers the next. By the video's end, each cup has filled or spilled, and each fire has gone out. Now if only everything in "Useless" were as fully functional and as defiantly useless.

Looking backward

The search for intelligent life in the universe is never easy. Since signals from distant galaxies can travel only at the speed of light, it depends on where and when you look. One might say the same about the search for intelligent art in Queens, in "Mundos Alternos" at the Queens Museum. One can hardly miss limp fabric tubes running the length of its glorious central hall.  Stumble on the right hour, though, and the squiggles open into arches through which visitors may pass, on the way to a meeting of improvised architecture and organic form. Even then, has one really found, as the exhibition's subtitle has it, a meeting of "art and science fiction in the Americas"?

Stumble on the right hour, though, and the squiggles open into arches through which visitors may pass, on the way to a meeting of improvised architecture and organic form. Even then, has one really found, as the exhibition's subtitle has it, a meeting of "art and science fiction in the Americas"?

What are these life forms anyway, the giant Gummi Bears of Mars? Chico MacMurtrie speaks of them as "amorphic robots," but the technology here is decidedly low tech. He sees himself as a time traveler, but (to borrow the title of a classic utopian novel by Edward Bellamy) he is looking backward. If you were addicted to one generation or other of Star Trek, you know that the final frontier has some nasty inhabitants, but the mission and its crew are models of diversity and good intentions. So, too, is the entire exhibition. Still, can it offer much in the way of science or fiction?

Given the moment, art and science can hardly help looking back. The museum fills a former exhibit building at the 1964 World's Fair—where Alexandria Smith pays tribute to a nearby African American burial ground. And Glexis Novoa takes a fine pencil to the walls of that central hall, for tiny drawings of what appear to be fair grounds and drones entering space. This is also the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing, the subject of "Apollo's Muse" at the Met, and Adál imagines an encounter there with a lunar native and coconuts. In his telling, the United States leveled or ignored them both, just as Donald J. Trump seems out to level or ignore Puerto Rico, much less Puerto Rican art. Erica Bohm takes a shot at reclamation by photographing NASA images.

Still, Bohn's art is looking back—not just to the moon, but also to the trope of rephotography, like that of Sherrie Levine after Walker Evans. More culturally aware, Guillermo Bert looks to a decline in Chile's native weavers by commissioning tapestries. Each bears a QR code, which leads cells phones with scanners to local wisdom. Beatriz Cortez looks back further still for her act of preservation, with a recording of the last of California's Yahi Indians in 1916. A nearby box prints out his wisdom, too, at the push of a low-tech button. Tania Candiani looks back all the way to the seventeenth century, for engravings after occult practices.

The show's themes tend to run together, like "indigenous futurisms" and "alternate Americas." It does have a room for actual science fiction in film and graphic novels, the kind that Dewey Crumpler in paint calls his own. Alex Rivera pictures a dystopia in which migrant workers fall prey to controlling robots. It also has an alcove for sheer fantasy, like a nude astronaut cherishing a green-skinned alien, in a painting by Debra Kuetzpal Vasquez with the MeChicano Alliance of Space Artists, or MASA. On video for José Luis Vargas, men in suits conduct a séance to evoke the spirit of Third World independence. Now if only they, too, could shed their skin.

As with MacMurtrie's organic arches, the artists do best on the scale of installations. That lone Yahi voice emerges from the interior of a space capsule, its outer surface a cracked mirror. Clarissa Tossin turns plaster, electronic waste, and cedar from the forests of Brazil into a fallen totem, as Future Fossil. With his Autonomous InterGalactic Space Program, Rigo 23 contains multitudes—volunteers who contribute paintings to a spiraled chamber that opens onto a wooden spaceship in the form of an ear of corn or a canoe, for more reminders of what a space program may discover or leave behind. Still, he is no less ragtag and optimistic, in an exhibition that hardly dares think of the future. "We Want," paintings read in Spanish and English, "a World Where Many Worlds Fit," but no one quite fits in.

"Useless" ran at the Bronx Museum through September 1, 2019, "Mundos Alternos" at the Queens Museum through August 18, with a continuation at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.