Some Trees

John Haberin New York City

Ellen Altfest, Anya Gallaccio, and Tacita Dean

Converted city factories and warehouses may sound remote from nature. Art, however, has long had a penchant for landscape. Three exhibitions now manage to recover some of its interest, but by dropping the genre altogether, in favor of still-life painting, appropriation, installation, and new media. In different ways, they unsettle the border between a gallery and the natural world.

Ellen Altfest gives the illusion of art and wood together as they recompose and die, while thanks to Anya Gallaccio a majestic cherry tree seems to rise again from the dead. Last, a video by Tacita Dean aspires as much to the Old Masters as to new media. John Ashbery opens his "Some Trees," his 1956 poem, this way: "They are amazing. . . . / That their merely being there / means something." These artists are definitely after amazement.

Still lifes and still lives

Still life has always enshrined a paradox: things in this world refuse to sit still. That implicit defiance of age itself, quite as much as the glory of illusion, accounts for its appeal in art.

It helps explains why Caravaggio allows fruit to rot, in a basket that totters so precariously over an edge, or why one counts Martin Johnson Heade's flowers among the grander scenes of the American sublime. It helps explain those animals leaping amid J.-S. Chardin's ledges. It may even suggest the ease with the modern still life veers into found objects, from Cubism to Susan Jane Walp. The gritty, decaying "combines" of Robert Rauschenberg actually include clocks, which of course tell time as often as twice a day.

Ellen Altfest's "Still Lives" embrace decay in a big way, but growth as well. One could almost call her art a miniature ecosystem, like many an installation these days. Certainly her painting belongs squarely in the still-life tradition. She sustains a meticulous illusion, but without the harsh, dry air of Ivan Albright or Philip Pearlstein. She adopts all the hallmarks of trompe l'oeil, including subdued color, forms aligned with the picture plane except when they happen to thrust forward, and illusionistic frames within frames. The cactus plant would look just fine in a New York apartment, as would the skies that occasionally show through, and one can almost ignore that somehow cactus and tumbleweed have drifted into town from an uncertain landscape.

However, Altfest is not out either to defy time or to moralize over it. Note the unusual plural still lives, with the ambiguity of lives. She makes it hard enough to tell growth from decay, with both as a kind of accumulation. The apparent frames crack or peel outward in successive layers, with much of the work's richest color. Twigs weave tightly across the picture plane or fall to the ground beneath. Non compost mentis.

The shallow space of still life supplies another reason for its past accommodation to Modernism. Even when it retains the naughty concept of illusion, it at least partly closes the shade on painting as window. It also has the potential for blurring the line between drawing and painting, just as fans of Jackson Pollock might wish. Sure enough, one may recognize his designs in those twigs and the dark, shallow space that they enclose. Altfest's preferred tawny colors have an appropriately autumnal rhythm. The pale, woody tones might make one think of Andrew Wyeth, I suppose, if only he understood modern art—or, for that matter, if only he drew half as realistically as reputation has it.

One need not be a sucker for illusion, subdued light, and formalist painting to like the show. The imagined decay could make one abandon the clean, well-preserved frames of traditional painting for good.

Losing it

Did someone say go climb a tree? If Altfest gives the illusion of watching wood peel, her gallery's previous artist, Marc Swanson, built his own New England forest. Its branches amounted to a less than natural ecosystem, concealing all sorts of occupants and their debris. A couple of biennials ago, Roxy Paine added his artificial tree to Central Park, although one in materials more suited to Joel Shapiro than the Tin Man. In his latest show, Paine even supplies the rotting landscape and "erosion machine" for an age of corporate forest depletion. Art has come a long way indeed from Asher Durand's nineteenth-century vision of nature and American culture as Kindred Spirits.

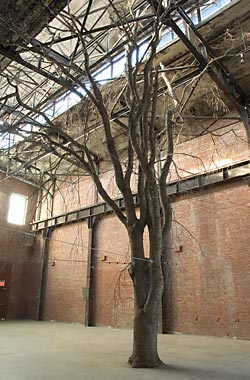

Facing the woods, must one see bare ruined choirs, with only the discipline of art to compensate for a literal rootlessness? Anya Gallaccio sure seems to think so. Perhaps a tree still grows in Brooklyn (or, for Hugh Hayden, in Madison Square Park), but just across Newtown Creek, in Long Island City, she raises a weeping cherry. And I mean a real tree. Bare of leaves and cut off cleanly at the roots, it fills the main hall of SculptureCenter. Not even Marcel Duchamp's urinal or Damien Hirst's shark tank does so little to transform a found object.

Gallaccio means to evoke loss and recovery, like art after climate change, starting with the wintry branches and a natural history of destruction. She salvaged the tree after street construction had inadvertently torn apart its root structure. She also titles the work One Art, after Elizabeth Bishop's poem of lost love. The simplicity of its appropriation echoes the poem's opening line: "the art of losing isn't hard to master." Why, a two-year-old child with a sufficiently large construction crew could do that.

One can invoke all sorts of associations. In The New York Times, Ken Johnson tosses in everything from a crucifixion to Saint Sebastian, although thankfully he leaves out the forest nymphs. Sometimes, though, a tree is only a tree. Bishop herself stands at opposite poles from the work. Where Bishop's headlong rhythms make lost love heartbreakingly inevitable, Gallaccio finds a quiet time alone, with a tree far older than any human life. Where a villanelle displays the poet's compulsive craft, the artist adds little more than the bolts and heavy wires that anchor the work to the gallery walls.

For all those reasons, I dreaded the whole affair. Simply by pruning away unneeded interpretation, however, I found a beautiful show. True to its theme, it presents something at once natural and unnatural. It recalls that Minimalist dream of a space in which art, viewer, and the gallery come together. One sees the wires, plain as day and just above eye level, and one can marvel at how perfectly the tree's symmetry conforms to its space. Its height and spread push up against the walls and skylight, while small twigs hang down to brush against one's arms.

One Art benefits from the room. Where the hush of Paula Cooper gallery's cavernous interior, pristine walls, and pointed ceiling threatens to overwhelm any art, Maya Lin allows SculptureCenter to resemble at any moment a warehouse, a factory, a cathedral, or a scrappy display space, with none of these privileged above the others. Perhaps even the contrast with Bishop projects the Scottish-born, London-based artist's understanding of loss. The work's stark, slow pace goes best with dark northern skies, and its avoidance of the American poet's confessions makes me think of a British stiff upper lip.  Something still comes too cheaply, like the tree's history, which all but announces the politically correct message "no living things were destroyed to make this art." However, one may never feel one's shoulders touching the entirety of that great hall again.

Something still comes too cheaply, like the tree's history, which all but announces the politically correct message "no living things were destroyed to make this art." However, one may never feel one's shoulders touching the entirety of that great hall again.

Downstairs, as part of a group show another monument to loss hides behind a darker curtain, virtually in the middle of SculptureCenter's narrow passageways, and the desk clerk has to tell one to take care not to miss it. With The Editor of Misfortunes/Miseries, Monika Zarzeczena has created a small studio, where a desk lamp casts its stark shadow. Drawings in colored pencil lie across the drafting table, as if unfinished, with many more stuck up on the walls and still others crumpled in wads on the floor. The drawings show people in ambiguous postures of sleep, agony, or death. The editor of the title may have given up in frustration or died, too. Do the drawings—and the vehemence with which they lie half discarded—express the artist's inner miseries, multiply anonymous ones, or attest to the misery of not successfully expressing either one? I felt almost the need to sit at the desk, in order to bring the narrative to completion, but I feared encountering my own misfortunes in the act.

Celluloid heroes

Tacita Dean, who has also made films or artists, calls her celluloid elm a hybrid of photography and painting, much like trees for Louise Dudis (anticipating what Wave Hill calls "Trees, We Breathe"). That sounds way cooler and more futuristic than she could wish. One should take hybrid literally, not as new media, but as a new creature. Dean has a problem with technological innovation—and a fascination with the aura of a work of an old-fashioned work of art. Where a digital artist might nurture the absences even in portraiture, she clings to presences everywhere.

She has not so much joined media anyway as layered them and traced their outlines. For Majesty (Portrait), she prints the tree onto two huge sheets, divided along the vertical to emphasize the height of the work and its subject. Then she painstakingly applies white paint, working around the trunk and branches. The background shows through the white, as if seen through a storm or freshly fallen snow. It animates the scene, emphasizes by contrast the stillness of the tree, and roots them both in traditions of the sublime and the picturesque, long before today's art of endangered places. The title says it all, in its intimations of grandeur and animal spirits within nature and art alike.

The rest of her Hugo Boss Prize installation grieves for the loss of old media and those who made them. Noir et Blanc takes nearly three quarters of an hour to document a Kodak facility in France. Her own search for sixteen-millimeter film drew her to it. So did learning of its impending closure, and every step in her process pays respect. She creates her rear-screen projection on film salvaged from the plant. She displays a strip of it by the entrance, with the perforations coming to an abrupt halt along the bottom edge.

Dean calls the film strip Found Obsolescence. The appropriation and self-reference in her materials has more than enough wit. No doubt planned economies or planned cities have gone out of fashion, along with the lone artist's impulse for authenticity. Inside the plant, however, Dean's respect takes over entirely from her sense of humor. People, perhaps herself and her crew, enter with the grave air of a HazMat team. Production may continue throughout filming, but one would hardly know from the empty interiors.

They look ghostlier still filmed in shades of orange and black. In this light, Dean could avoid exposing film other than her own. A last jumble of black and white plays on a screen just outside—a document of film production in its other sense, of exposure, development, and projection. As artists go, she definitely thinks in noir and blanc, although that lack of nuance sounds so much more postmodern in French. Perhaps a nostalgia for formal history and old meanings comes with the territory of British art, or perhaps it comes with the Hugo Boss Prize, given in 2008 to Emily Jacir. The previous winner, Rirkrit Tiravanija in 2005, tried to subvert media monopolies with his own radio signals.

I have a problem with putting art so much on a pedestal—or even a tripod. One can see why the show got an immediate rave in The Sun, New York's most conservative paper. I also do not share a concern that film is on its way out, even if it mattered, judging by high-resolution images from Jeff Wall or Catherine Yass. I may wish, too, that Dean had balanced her reverence with humor as adeptly as she commingles presences and absences. However, any work of art attests to many others, both seen and unseen—itself, its creators, its viewers, and the worlds they inhabit. Dean has the decency to respect them and the self-awareness to make them her subject, even if she thinks in terms of black and white.

Ellen Altfest ran at Bellwether through January 21, 2006, Anya Gallaccio and Monika Zarzeczena at SculptureCenter through April 3, and Roxy Paine at James Cohan through February 25. Tacita Dean's Hugo Boss Prize work ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through June 6, 2007. A related review looks at Roxy Paine indoors and in wood.