From the Tube to the Sky

John Haberin New York City

Before Projection and a Video Eclipse

Erin Shirreff, Tomás Saraceno, Doug Aitken

Programmed

Just what was so new about new media? Maybe not as much as you thought, not when SculptureCenter can present its history from 1974 to 1995 as "video sculpture." If that has you staring too hard at the monitor, other video artists were staring at the sky for a solar eclipse.

Not that talk of sculpture is merely in deference to the center's mission. Its eleven artists could not yet benefit from high-res digital. They could not command towering images in treacherously dark rooms.  For the curator, Henriette Huldisch of MIT's List Visual Arts Center, they were set against TV and cinema alike, and what set them apart was the monitor. It gave them a challenge to the image as an unmediated reality. It left them "Before Projection."

For the curator, Henriette Huldisch of MIT's List Visual Arts Center, they were set against TV and cinema alike, and what set them apart was the monitor. It gave them a challenge to the image as an unmediated reality. It left them "Before Projection."

It also left them between Minimalism and the computer. Consider twenty words from 1976. 24 lines from the center, 12 lines from the midpoint of each of the sides, 12 lines from each corner. It is not just the title of a work by Sol LeWitt, but a program for its execution. And it is not just a mouthful, but an eyeful. Its white lines scurry across a black wall, gaining in radiance at the center and each of its two dozen nodes.

If LeWitt had thought of it a century before, would it have become punch cards in a Jacquard loom? If he were alive today, would it have become a macro or an app? Probably not, not when others his age were discovering FORTRAN, Basic, and computer art at MIT, ATT, and Ohio State. He holds his own, though, along with them in "Programmed" at the Whitney. Where others have seen Minimalism as blunt industrial materials, it sees an analog precursor to digital art. In turn, TV-based art starts to look not so much virtual as exuberant and solid.

Video as sculpture

The monitor served back then as a precondition for video art, SculptureCenter argues, starting with the picture tube. Maria Vedder erects a wall of CRTs, to tease out competing standards for color TV in North America and Europe. Diana Thater settles more simply for red, yellow, and blue, while Muntadas skips right ahead to the credits. Mary Lucier records sunrise over seven days on as many monitors, letting the light burn its path onto the tube. Others take a greater interest in the box. For Tony Oursler, it is just one sculptural element among others, alongside a medieval castle and nuclear cooling tower—and do not ask what lurks inside.

Takahiko Iimura allows paired videos to face off. His monitors must once have passed for luxury—only here they stand face to face with barely a hint of light between them. Ernst Caramelle uses his paired sets for Video Ping Pong. An actual ping-pong table behind them only emphasizes their solidity, except for one thing: the players, male and female, are only miming while sounds simulate impact. Each of two paddles on the table rests on a ball, as if they cannot agree on where the game will begin.

The face-off is gendered for Dara Birnbaum as well. She kneels on one monitor, camera in hand, while snapping away at the four encroaching men on the other. It is physical, too, for Friederike Pezold, who stacks four monitors for eyes, lips, breasts, and pubic hair. She darkens each as well, to heighten their gender or the comedy. Shigeko Kubota places monitors face down above a trough of water. A motor keeps the water lapping while she swims, except when the images hold only colored patterns.

Nam June Paik takes one back to the medium's birth and his collaboration with Charlotte Moorman—and who could be more sculptural? Her cello serves as her torso and a viola as the arm that would have held a bow. A dozen more TVs supply her shifting image and the remainder of her head and limbs. They, too, call attention to the box, thanks to their age. They look less like the TV that I remember from childhood than like old desktop radios. Then again, this was a musical performance.

Something, though, is missing from this tidy history. It has little room for the cerebral rather than embodied, as with another video pioneer, Gary Hill. It downplays how much the displays dissolve or distort a bodily presence at that, with Kubota reduced to reflections in moving water. It also takes video further from cinema than it could ever claim to be. Maybe one can disentangle it from underground film by the likes of Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, and Andy Warhol, but I cannot. And maybe Bill Viola and his operatic video found their potential only in projection, but he, too, was there long ago.

If Viola connects video to wide-screen movies, he is not alone. Theter takes her images from classic westerns, and movies have closing credits, too. And performance video had a parallel track in Bruce Nauman, Chris Burden, and their "mediascape." If they seem too self-involved for their own good, think back to Annette Michelson, who titled her article for the founding issue of October magazine "The Aesthetics of Narcissism." Maybe only Paik could transcend narcissism, even in performance. When his clay Buddha contemplates a candle in place of a picture tube, something beyond sculpture is about to begin.

Eclipse of the heart

A partial eclipse in August 2017 drew Americans out of the workplace to stare at the sky. It seemed to play as many tricks with the cloud cover and classic skyscrapers as with the sun. I may remember it most, though, from the spectacle in a gallery. Erin Shirreff made it her inspiration for Son. The video consists of a bright, slowly shifting circle—an animation that must have required only patience, cut paper, and blue light. It is, in the very best sense, all show.

So is "Solar Rhythms," by Tomás Saraceno. Its opening just as evening sunlight was becoming visible is only a coincidence, since Saraceno has been working away on his project for some time, but his claims are just as spectacular and just as artificial. He claims to be applying solar rhythms to solar-powered flight.  So far, he has kept seven passengers aloft above White Sands, New Mexico, for two hours or so, but he sees himself as changing society to counter global warming. Two videos document his experiments, and the Aerocene Float Predictor on laptop invites others to join in. I chose to remain a spectator.

So far, he has kept seven passengers aloft above White Sands, New Mexico, for two hours or so, but he sees himself as changing society to counter global warming. Two videos document his experiments, and the Aerocene Float Predictor on laptop invites others to join in. I chose to remain a spectator.

Spectacle is the order of the day, too, for Doug Aitken, and so is the claim to usher in a new age. His title, New Era, refers in part to a mere distraction from eternity, the cell phone. The maker of the first such device describes the first call as he stands on camera. His white Motorola still looks ready for mass reproduction. Soon enough, though, he gives way to an epic landscape on three channels—with kaleidoscopic reflections on the remaining walls of a six-sided room. The era of selfies is giving way to the end of 2001.

Aitken revels in excess, just as with his projection on a museum tower and gaping hole in a gallery floor. The first enlarged and glamorized working New Yorkers. The second evoked a meteor impact that could shortchange global warming after all. Saraceno's craft is going nowhere fast, and its flight looks no more daring than that of a glider. His designs also lead to glass spheres somewhere between futurism for Buckminster Fuller and pricey knickknacks. He adapted a similar shape for his Cloud City on the roof of the Met.

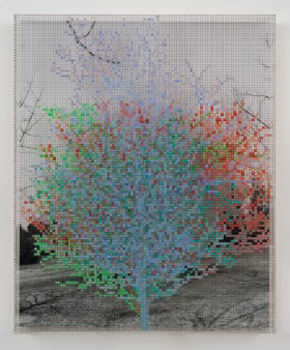

Shirreff still bridges photography, land art, and Minimalism, as with her photograms and pressed ashes. Her subject encompasses both the materials of art and perceptual changes. Other new work applies the halftone dots of found images to cut aluminum and collage. And their shapes take on a third dimension in white. Still, the sculpture looks bland beside her earlier work—and never mind the pun on Son for art in gestation over nine months since the eclipse. I can hear Hamlet replying, "I am too much in the sun."

They are spectacular all the same. They pick up the legacy of new media as a record of natural processes and human excess, as with Black Sun for Sue de Beer. Video takes flight when Saraceno moves to a larger scale in the gallery's main room. The polyhedra and light show come together as a thing of beauty. And Shirreff allows still more time for astonishment. Her memories of the eclipse have become mine.

Get with the program

Sol LeWitt could exemplify all three aspects of the Whitney's subtitle, "Rules, Codes, and Choreographies," including the dance. So does his collaboration with Lucinda Childs, the choreographer, with music by Philip Glass. The show throws in a score by Glass as well, as instructions for its pulsing execution. It also pairs text art of the 1960s with code from William Bradford Paley in 2002. Where the words are their own product for Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner, Paley's are just an additional layer beneath the curves of light that they generate. As for the loom, Mika Tajima adopts factory technology for her abstract "portraits" and tribute to craft.

If this sounds forced, Casey Reas bases his 2004 software on LeWitt, while John F. Simon, Jr., derives his PC color mixing from Homage to the Square by Josef Albers. Veterans of Minimalism and land art like Agnes Denes, Charles Csuri, and Charles Gaines in turn find their way from architecture and orchards to mathematical doodles. Still others take found systems as raw materials. Frederick Hammersley in 1969 and Tauba Auerbach again in 2005 start with alphabets. Cheyney Thompson in 2013 cedes design of his concrete to a random walk (the proverbial drunk under a lamppost), while Ian Chang lets chatbots "talk" to one another as best they can. "Hang on," for "I am thinking."

For the Whitney, these artists take "conceptual ideas as a driving force." They are, though, only half of a quirky history of new media, beginning in 1965. Then comes what is seen and not seen on TV. Some do their best to get in the way of the picture tube, leaving a sculptural presence and distorted lights. Nam June Paik places a hefty magnet on top of the set, while Earl Reiback thrusts his sculpture into the box before adding back the CRT. As late as 2002, Cory Arcangel still trusts Super Mario clouds to enter the third dimension.

Another group thrives on TV, with a little help from the artist to undermine its authority and to liberate its energy. Paik has some two hundred sets, with gateways so that one can literally see behind the curtain. Siebren Versteeg takes her video collage from the Internet, while Barbara Lattanzi adds closed captions from Jean-Luc Godard to a Pentagon press briefing. Steina seems downright nostalgic by comparison, with projected landscape drawings in sepia tones or black and white. And the new in new media has a way of dating quickly, and Lynn Hershman Leeson knew it all along. She produced the first interactive art on laser disc in 1979, asking one into her avatar's living room—with a green land line, old issues of Time on the floor, and leopard skin upholstery for her easy chair.

The curators, Christiane Paul and Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, have a point in leaping across generations. They do less well at a survey of new media. They have a fair excuse in what amounts largely to a display of the permanent collection. They allow Jim Campbell a low-hanging alcove for his Tilted Plane of LEDs, driving into space. They commission Tamiko Thiel to insert "organic growth" virtually into the sixth-floor terrace, as a "parallel dimension." Those who want to take it further can download an app.

Still, the show can feel selective and its seven divisions arbitrary (and the links in this review will point you to alternatives). I had just come from Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, with pixils of the gallery entrance that adds a greater interactivity and a reminder of surveillance cameras. So in their way do Eckhaus Latta in the Whitney's lobby gallery. Once one allows in LLeWitt, Albers, and Donald Judd, practically anything could fit. Meanwhile the bow to a "critical stance" feels pro forma, despite the witty pretense of a "skin color verification system" by Mendi + Keith Obadike. Jonah Brucker-Cohen and Katherine Moriwaki pick up the dark side of patriotism and tweets with Americas Got No Talent from 2012—but not even art can match the sad reality of a president from reality TV.

"Before Projection" ran at SculptureCenter through December 17, 2018, Erin Shirreff at Sikkema Jenkins through May 19, Tomás Saraceno at Tanya Bonakdar through June 9, Doug Aitken at 303 through May 25, and Rafael Lozano-Hemmer at Bitforms through October 21. "Programmed" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through April 14, 2019.